Urbanization is the study of the social, political, and economic relationships in cities, and someone specializing in urban sociology would study those relationships. In some ways, cities can be microcosms of universal human behavior, while in others they provide a unique environment that yields their own brand of human behavior. There is no strict dividing line between rural and urban; rather, there is a continuum where one bleeds into the other. However, once a geographically concentrated population has reached approximately 100,000 people, it typically behaves like a city regardless of what its designation might be.

According to sociologist Gideon Sjoberg (1965), there are three prerequisites for the development of a city. First, good environment with fresh water and a favorable climate; second, advanced technology, which will produce a food surplus to support non-farmers; and third, strong social organization to ensure social stability and a stable economy. Most scholars agree that the first cities were developed somewhere in ancient Mesopotamia, though there are disagreements about exactly where. Most early cities were small by today’s standards, and the largest city at the time was most likely Rome, with about 650,000 inhabitants (Chandler and Fox 1974). The factors limiting the size of ancient cities included lack of adequate sewage control, limited food supply, and immigration restrictions. For example, serfs were tied to the land, and transportation was limited and inefficient. Today, the primary influence on cities’ growth is economic forces. Since the recent economic recession has reduced housing prices, researchers are waiting to see what happens to urban migration patterns in response.

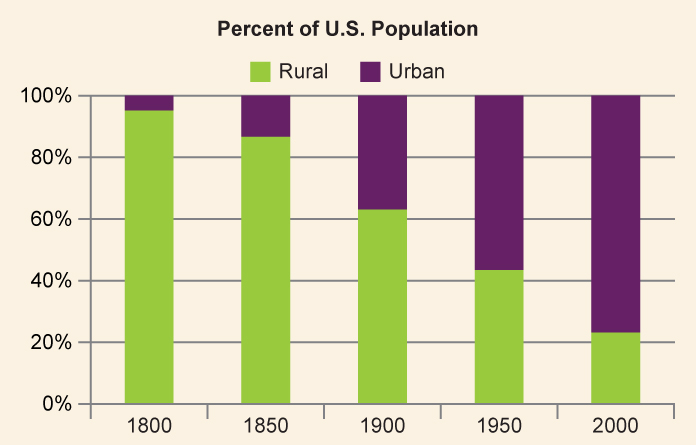

Urbanization in the United States proceeded rapidly during the Industrial Era. As more and more opportunities for work appeared in factories, workers left farms (and the rural communities that housed them) to move to the cities. From mill towns in Massachusetts to tenements in New York, the industrial era saw an influx of poor workers into America’s cities. At various times throughout the country’s history, certain demographic groups, from recent immigrants to post-Civil War southern Blacks, made their way to urban centers to seek a better life in the city.

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle (1906) offers a snapshot of the rapid change taking place at the time. In the book, Sinclair explored the difficult living conditions and hideous and unsafe working conditions in a Chicago-area meatpacking plant. The book brought the plight of the urban working poor to the front and center of the public’s eye, as well as turning the stomachs of most modern readers with its graphic discussion of food preparation before the advent of government regulation.

In 1906, Upton Sinclair’s book of the harsh life and difficult reality of the urban poor burst onto the scene. Almost 100 years later in 2003, Adrien Nicole LeBlanc wrote Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble, and Coming of Age in the Bronx. To write her book, LeBlanc spent 10 years with a family in the Bronx, New York, following their struggles, their daily lives, and the extreme difficulties of their urban existence. Her research methods and resulting work reflect the symbolic interactionist perspective of sociology. Unlike most nonfiction books that focus on urban poverty issues, Random Family is not about social or economic policies, declining teenage pregnancy rates, welfare reform, or any of the other critical issues that matter to this demographic. It is the story of a family, starting with two young women and following them through their relationships with abusive boyfriends, through their first jobs (as heroin packers), and through the births of their many children. LeBlanc does not judge them or offer advice, nor does she take the long view and offer perspective on what confluences of history brought them to this place. Instead, she allows readers to follow these young women on their painful attempt to get to a better place, despite having no idea which way to go.

The book is eye-opening and offers a compelling look at today’s urban life in an intimate portrait. The lives LeBlanc portrays are not unusual, nor does the book offer a trite solution. It does offer a personal and up-close view of the people who make up the distressing urban statistics that are part of American society.

As cities grew more crowded, and often more impoverished and costly, more and more people began to migrate back out of them. But instead of returning to rural small towns (like they’d resided in before moving to the city), these people needed close access to the cities for their jobs. In the 1850s, as the urban population greatly expanded and transportation options improved, suburbs developed. Suburbs are the communities surrounding cities, typically close enough for a daily commute in, but far enough away to allow for more space than city living affords. The bucolic suburban landscape of the early 20th century has largely disappeared due to sprawl. Suburban sprawl contributes to traffic congestion, which in turn contributes to commuting time. And commuting times and distances have continued to increase as new suburbs developed farther and farther from city centers. Simultaneously, this dynamic contributed to an exponential increase in natural resource use, like petroleum, which sequentially increased pollution in the form of carbon emissions.

As the suburbs became more crowded and lost their charm, those who could afford it turned to the exurbs, communities that exist outside the ring of suburbs and are typically populated by even wealthier families who want more space and have the resources to lengthen their commute. Together, the suburbs, exurbs, and metropolitan areas all combine to form a metropolis. New York was the first American megalopolis, a huge urban corridor encompassing multiple cities and their surrounding suburbs. These metropolises use vast quantities of natural resources and are a growing part of the U.S. landscape.

What makes a suburb a suburb? Simply, a suburb is a community surrounding a city. But when you picture a suburb in your mind, your image may vary widely depending on which nation you call home. In the United States, most consider the suburbs home to upper and middle class people with private homes. In other countries, like France, the suburbs––or “banlieues”–– are synonymous with housing projects and impoverished communities. In fact, the banlieues of Paris are notorious for their ethnic violence and crime, with higher unemployment and more residents living in poverty than in the city center. Further, the banlieues have a much higher immigrant population, which in Paris is mostly Arabic and African immigrants. This contradicts the clichéd American image of a typical white-picket-fence suburb.

In 2005, serious riots broke out in the banlieue of Clichy-sous-Bois after two boys were electrocuted while hiding from the police. They were hiding, it is believed, because they were in the wrong place at the wrong time, near the scene of a break-in, and they were afraid the police would not believe their innocence. Only a few days earlier, interior minister Nicolas Sarkozy (who later became president), gave a speech touting new measures against urban violence and referring to the people of the banlieue as “rabble” (BBC 2005). After the deaths and subsequent riots, Sarkozy reiterated his zero tolerance policy toward violence and sent in more police. Ultimately, the violence spread across more than 30 towns and cities in France. Thousands of cars were burned, many hundred were arrested, and both police and protesters suffered serious injuries.

Then-President Jacques Chirac responded by pledging more money for housing programs, jobs programs, and education programs to help the banlieues solve the underlying problems that led to such disastrous unrest. But none of the newly launched programs were effective. President Sarkozy ran on a platform of tough regulations toward young offenders, and in 2007 the country elected him. More riots ensued as a response to his election. In 2010, Sarkozy promised “war without mercy” against the crime in the banlieues (France24 2010). Six years after the Clichy-sous-Bois riot, circumstances are no better for those in the banlieues.

As the above feature illustrates, the suburbs also have their share of socio-economic problems. In the U.S., the trend of white flight refers to the migration of economically secure white people from racially mixed urban areas toward the suburbs. This has happened throughout the 20th century—due to causes as diverse as the legal end of racial segregation established by Brown v. Board of Education to the Mariel boatlift of Cubans fleeing Cuba’s Mariel port for Miami. The issue only becomes more complex as time goes on. Current trends include middle-class African-American families following “white flight” patterns out of cities, while affluent whites return to cities that have historically had a black majority. The result is that the issues of race, socio-economics, neighborhoods, and communities remain complicated and challenging.

As was the case in America, other coronations experienced a growth spurt during the Industrial Era. The development of factories brought people from rural to urban areas, and new technology increased the efficiency of transportation, food production, and food preservation. For example, from the mid-1670s to the early 1900s, London increased its population from 550,000 to 7 million (Old Bailey Proceedings Online 2011). The most recent phenomenon shaping urbanization around the world is the development of postindustrial cities whose economic base depends on service and information rather than the manufacturing of industry. The professional, educated class populates the postindustrial city, and they expect convenient access to culturally based entertainment (libraries, museums, historical downtowns, and the like) uncluttered by factories and the other features of an industrial city. Global favorites like New York, London, and Tokyo are all examples of postindustrial cities. As cities evolve from industrial to postindustrial, gentrification becomes more common. The practice of gentrification refers to members of the middle and upper classes entering city areas that have been historically less affluent and renovating properties while the poor urban underclass are forced by resulting price pressures to leave those neighborhoods. This practice is widespread and the lower class is pushed into increasingly decaying portions of the city.

As the examples above illustrate, the issues of urbanization play significant roles in the study of sociology. Race, economics, and human behavior intersect in cities. Let’s look at urbanization through the sociological perspectives of functionalism and conflict theory. Functional perspectives on urbanization focus generally on the ecology of the city, while conflict perspective tends to focus on political economy.

Human ecology is a functionalist field of study that focuses on the relationship between people and their built and natural physical environments (Park 1915). Generally speaking, urban land use and urban population distribution occurs in a predictable pattern once we understand how people relate to their living environment. For example, in the United States, we have a transportation system geared to accommodate individuals and families in the form of interstate highways built for cars. In contrast, most parts of Europe emphasize public transportation such as high-speed rail and commuter lines, as well as walking and bicycling. The challenge for a human ecologist working in American urban planning would be to design landscapes and waterscapes with natural beauty, while also figuring out how to provide for free flowing transport of innumerable vehicles—not to mention parking!

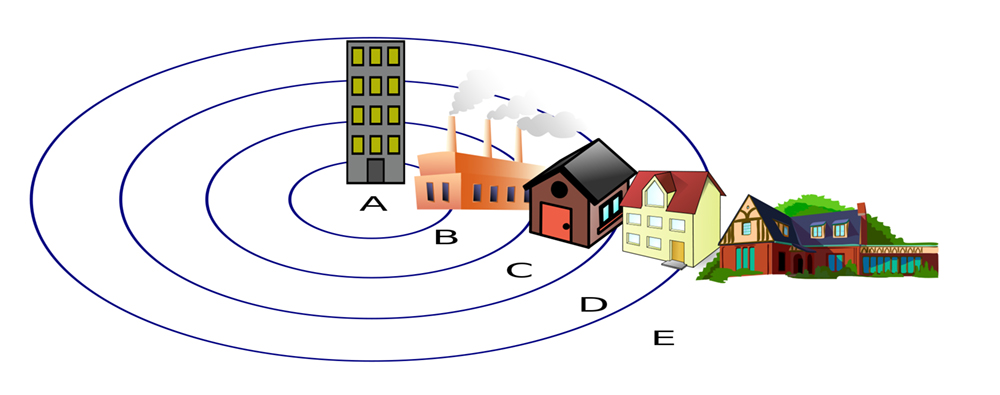

The concentric zone model (Burgess 1925) is perhaps the most famous example of human ecology. This model views a city as a series of concentric circular areas, expanding outward from the center of the city, with various “zones” invading (new categories of people and businesses overrun the edges of nearby zones) and succeeding (after invasion, the new inhabitants repurpose the areas they have invaded and push out the previous inhabitants) adjacent zones. In this model, Zone A, in the heart of the city, is the center of the business and cultural district. Zone B, the concentric circle surrounding the city center, is composed of formerly wealthy homes split into cheap apartments for new immigrant populations; this zone also houses small manufacturers, pawn shops, and other marginal businesses. Zone C consists of the homes of the working class and established ethnic enclaves. Zone D consists of wealthy homes, white-collar workers, and shopping centers. Zone E contains the estates of the upper class (exurbs) and the suburbs.

In contrast to the functionalist approach, theoretical models in the conflict perspective focus on the way that urban areas change according to specific decisions made by political and economic leaders. These decisions generally benefit the middle and upper classes while exploiting the working and lower classes.

For example, sociologists Feagin and Parker (1990) suggested three aspects to understanding how political and economic leaders control urban growth. First, economic and political leaders work alongside each other to affect change in urban growth and decline, determining where money flows and how land use is regulated. Second, exchange value and use value are balanced to favor the middle and upper classes so that, for example, public land in poor neighborhoods may be rezoned for use as industrial land. Finally, urban development is dependent on both structure (groups such as local government) and agency (individuals including businessmen and activists), and these groups engage in a push-pull dynamic that determines where and how land is actually used. For example, NIMBY (Not In My Backyard) movements are more likely to emerge in middle and upper-class neighborhoods, so these groups have more control over the usage of local land.

For some women, caring for their children is a part of everyday life. For others, caring for other people’s children is a job, and often it is a job that takes them away from their own families and increasingly, their own countries. Feminist sociologists (a branch of the conflict theory perspective) find topics like these rich sources of research for the discipline.

A 2001 article by sociologist Arlie Hochschild in American Prospect magazine discusses the global phenomenon of women leaving their own families behind in developing countries in order to come to America to be a nanny for wealthy U.S. families. These women’s own children, left behind, might be looked after by an older sibling, a spouse, or a paid care worker. These workers leave their countries to earn $400 a week as a nanny in the U.S., sending home $40 a week to pay the caregiver for their own children (Hochschild 2001). The Commercialization of Intimate Life is Hochschild’s book on the subject.

The statistics are startling. Over half the people immigrating to the United States are women, mostly between the ages of 25 and 34. Many of them find employment as domestic workers, and the demand for this type of care in the U.S. is rising. The number of American women in the workforce rose from 28.8 percent in 1950 to 47 percent in 2010 (Waite 1981; United States Department of Labor 2010). Simultaneously, the number of American families that rely on relatives to care for children is steadily decreasing. So the search for trusted, professional care for their children has become a priority worth paying for.

So what is the impact of these “global care chains,” as the article calls them? What does it mean for the children left behind? The American children being cared for? The parents? There are no easy answers to these questions, but it does not mean they should not be asked.

Just as a conscientious consumer would pay attention to the company that makes her sneakers or computer, so too do we need to pay attention to who is sacrificing what to care for core nation children. This is not to say it is exploitative to hire a nanny from overseas. Many women come to the United States expressly for the purpose of finding those jobs that enable them to send enough money home to pay for schooling and a better life. They do this in the hopes that, someday, their own children will have better opportunities (Hochschild 2001).

Cities provide numerous opportunities for their residents and offer significant benefits including access to goods to numerous job opportunities. At the same time, high population areas can lead to tensions between demographic groups, as well as environmental strain. While the population of urban dwellers is continuing to rise, sources of social strain are rising along with it. The ultimate challenge for today’s urbanites is finding an equitable way to share the city’s resources while reducing the pollution and energy use that negatively impacts the environment.

In the Concentric Zone model, Zone B is likely to house what?

C

What are the prerequisites for the existence of a city?

D

Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle examines the circumstances of the working poor people in what area?

C

What led to the creation of the exurbs?

A

How are the suburbs of Paris different than those of most U.S. cities?

C

How does gentrification affect cities?

B

What does human ecology theory address?

A

Urbanization includes the sociological study of what?

D

What are the differences between the suburbs and the exurbs, and who is most likely to live in each?

Most major cities in core countries are postindustrial. Can you think of an example of a growing city that is still in its industrial phase? How is it different from most U.S. cities?

Considering the concentric zone model, what type of zone were you raised in? Is this the same or different as that of earlier generations in your family? What type of zone do you reside in now? Do you find that people from one zone stereotype those from another? If so, how?

Interested in learning more about the latest research in the field of human ecology? Visit the Society for Human Ecology web site to discover what’s emerging in this field: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/human\_ecology

Getting from place to place in urban areas might be more complicated than you think. Read the latest on pedestrian-traffic concerns at the Urban Blog web site: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/pedestrian\_traffic

BBC. 2005. “Timeline: French Riots—A Chronology of Key Events.” November 14. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/4413964.stm).

Burgess, Ernest. 1925. “The Growth of the City.” Pp. 47–62 in The City, edited by R. Park and E. Burgess. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Chandler, Tertius and Gerald Fox. 1974. 3000 Years of Urban History. New York: Academic Press.

Dougherty, Connor. 2008. “The End of White Flight.” Wall Street Journal, July 19. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://online.wsj.com/article/SB121642866373567057.html).

Feagin, Joe, and Robert Parker. 1990. Building American Cities: The Urban Real Estate Game. 2nd ed. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

France24. 2010. “Sarkozy Promises War without Mercy for Paris Suburbs.” France 24, April 10. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://www.france24.com/en/20100420-sarkozy-war-suburbs-drugs-crime-violence-truancy-tremblay-en-france-saint-denis-france).

Hochschild, Arlie. 2001. “The Nanny Chain.” The American Prospect, December 19. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://prospect.org/article/nanny-chain).

LeBlanc, Adrien Nicole. 2003. Random Family: Love, Drugs, Trouble and Coming of Age in the Bronx. New York: Scribner.

Park, Robert. 1934 [1915]. “The City: Suggestions for Investigations of Human Behavior in the City.” American Journal of Sociology 20:577–612.

Park, Robert. 1936. “Human Ecology.” American Journal of Sociology 42:1–15.

Old Bailey Proceedings Online. 2011. “Population History of London.” Retrieved December 11, 2011 (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org/static/Population-history-of-london.jsp).

Sciolino, Elaine, and Ariane Bernand. 2006. “Anger Festering in French Areas Scarred in Riots.” New York Times, October 21. Retrieved December 11, 2011 (http://www.nytimes.com/2006/10/21/world/europe/21france.html?scp=2&sq=paris+suburb&st=nyt).

Sinclair, Upton. 1906. The Jungle. New York: Doubleday.

Sjoberg, Gideon. 1965. The Preindustrial City: Past and Present. New York: Free Press.

Talbot, Margaret. 2003. “Review: Random Family. Love, Drugs, Trouble and Coming of Age in the Bronx.” New York Times, February 9. Retrieved December 12, 2011 (http://www.nytimes.com/2003/02/09/books/in-the-other-country.html?pagewanted=all&src=pm).

United States Department of Labor. “Women in the Labor Force in 2010.” Retrieved January 23, 2012 (http://www.dol.gov/wb/factsheets/Qf-laborforce-10.htm).

Waite, Linda J. 1981. “U.S. Women at Work.” Santa Monica, CA: The Rand Corporation. Retrieved January 23, 2012 (http://www.rand.org/pubs/reports/2008/R2824.pdf).

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1

Attribution: