We recently hit a population milestone of seven billion humans on the earth’s surface. The rapidity with which this happened demonstrated an exponential increase from the time it took to grow from five billion to six billion people. In short, the planet is filling up. How quickly will we go from seven billion to eight billion? How will that population be distributed? Where is population the highest? Where is it slowing down? Where will people live? To explore these questions, we turn to demography, or the study of populations. Three of the most important components affecting the issues above are fertility, mortality, and migration.

The fertility rate of a society is a measure noting the number of children born. The fertility number is generally lower than the fecundity number, which measures the potential number of children that could be born to women of childbearing age. Sociologists measure fertility using the crude birthrate (the number of live births per 1,000 people per year). Just as fertility measures childbearing, the mortality rate is a measure of the number of people who die. The crude death rate is a number derived from the number of deaths per 1,000 people per year. When analyzed together, fertility and mortality rates help researchers understand the overall growth occurring in a population.

Another key element in studying populations is the movement of people into and out of an area. Migration may take the form of immigration, which describes movement into an area to take up permanent residence, or emigration, which refers to movement out of an area to another place of permanent residence. Migration might be voluntary (as when college students study abroad), involuntary (as when Somalians left the drought and famine-stricken portion of their nation to stay in refugee camps), or forced (as when many Native American tribes were removed from the lands they’d lived in for generations).

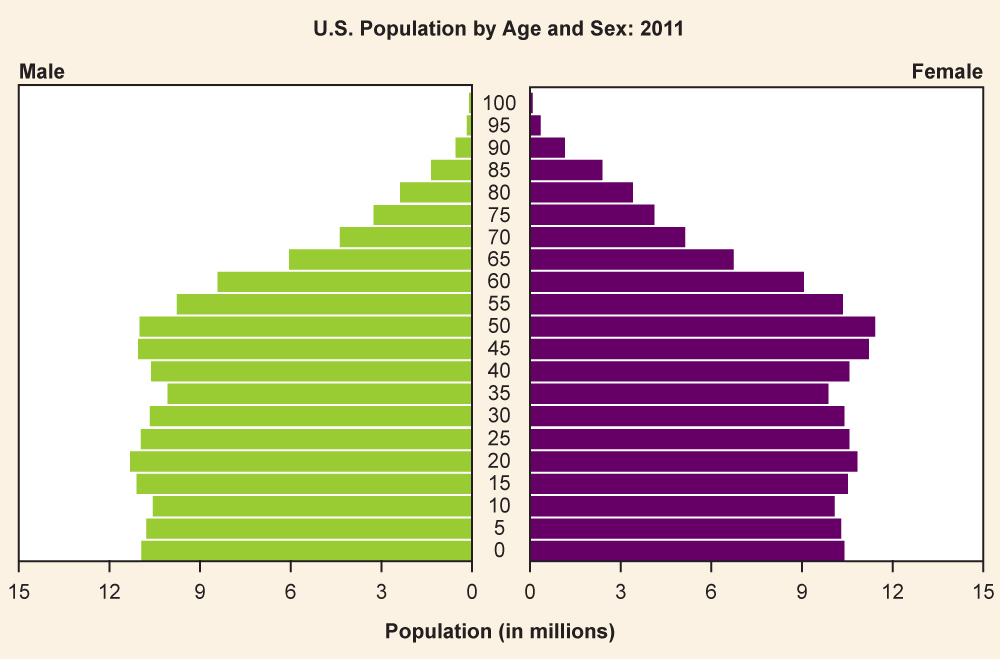

Changing fertility, mortality, and migration rates make up the total population composition, a snapshot of the demographic profile of a population. This number can be measured for societies, nations, world regions, or other groups. The population composition includes the sex ratio (the number of men for every hundred women) as well as the population pyramid (a picture of population distribution by sex and age).

| Country | Population (in millions) | Fertility Rate | Mortality Rate | Sex Ratio Male to Female |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afghanistan | 29.8 | 5.4% | 17.4% | 1.05 |

| Sweden | 9.1 | 1.7% | 10.2% | 0.98 |

| United States of America | 313.2 | 2.1% | 8.4% | 0.97 |

Comparing these three countries reveals that there are more men than women in Afghanistan, whereas the reverse is true in Sweden and the United States. Afghanistan also has significantly higher fertility and mortality rates than either of the other two countries. Do these statistics surprise you? How do you think the population makeup impacts the political climate and economics of the different countries?

Sociologists have long looked at population issues as central to understanding human interactions. Below we will look at four theories about population that inform sociological thought: Malthusian, zero population growth, cornucopian, and demographic transition theories.

Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) was an English clergyman who made dire predictions about earth’s ability to sustain its growing population. According to Malthusian theory, three factors would control human population that exceeded the earth’s carrying capacity, or how many people can live in a given area considering the amount of available resources. He identified these factors as war, famine, and disease (Malthus 1798). He termed these “positive checks” because they increased mortality rates, thus keeping the population in check, so to speak. These are countered by “preventative checks,” which also seek to control the population, but by reducing fertility rates; preventive checks include birth control and celibacy. Thinking practically, Malthus saw that people could only produce so much food in a given year, yet the population was increasing at an exponential rate. Eventually, he thought people would run out of food and begin to starve. They would go to war over the increasingly scarce resources, reduce the population to a manageable level, and the cycle would begin anew.

Of course, this has not exactly happened. The human population has continued to grow long past Malthus’s predictions. So what happened? Why didn’t we die off? There are three reasons that sociologists suggest we continue to expand the population of our planet. First, technological increases in food production have increased both the amount and quality of calories we can produce per person. Second, human ingenuity has developed new medicine to curtail death through disease. Finally, the development and widespread use of contraception and other forms of family planning have decreased the speed at which our population increases. But what about the future? Some still believe that Malthus was correct and that ample resources to support the earth’s population will soon run out.

A neo-Malthusian researcher named Paul Ehrlich brought Malthus’s predictions into the 20th century. However, according to Ehrlich, it is the environment, not specifically the food supply, that will play a crucial role in the continued health of planet’s population (Ehrlich 1968). His ideas suggest that the human population is moving rapidly toward complete environmental collapse, as privileged people use up or pollute a number of environmental resources, such as water and air. He advocated for a goal of zero population growth (ZPG), in which the number of people entering a population through birth or immigration is equal to the number of people leaving it via death or emigration. While support for this concept is mixed, it is still considered a possible solution to global overpopulation.

Of course, some theories are less focused on the pessimistic hypothesis that the world’s population will meet a detrimental challenge to sustaining itself. Cornucopian theory scoffs at the idea of humans wiping themselves out; it asserts that human ingenuity can resolve any environmental or social issues that develop. As an example, it points to the issue of food supply. If we need more food, the theory contends, agricultural scientists will figure out how to grow it, as they have already been doing for centuries. After all, in this perspective, human ingenuity has been up to the task for thousands of years and there is no reason for that pattern not to continue (Simon 1981).

Whether you believe that we are headed for environmental disaster and the end of human existence as we know it, or you think people will always adapt to changing circumstances, there are clear patterns that can be seen in population growth. Societies develop along a predictable continuum as they evolve from unindustrialized to postindustrial. Demographic transition theory (Caldwell and Caldwell 2006) suggests that future population growth will develop along a predictable four-stage model.

In Stage 1, birth, death, and infant mortality rates are all high, while life expectancy is short. An example of this stage is 1800s America. As countries begin to industrialize, they enter Stage 2, where birthrates are higher while infant mortality and the death rates drop. Life expectancy also increases. Afghanistan is currently in this stage. Stage 3 occurs once a society is thoroughly industrialized; birthrates decline, while life expectancy continues to increase. Death rates continue to decrease. Mexico’s population is at this stage. In the final phase, Stage 4, we see the postindustrial era of a society. Birth and death rates are low, people are healthier and live longer, and society enters a phase of population stability. Overall population may even decline. Sweden and the United States are considered Stage 4.

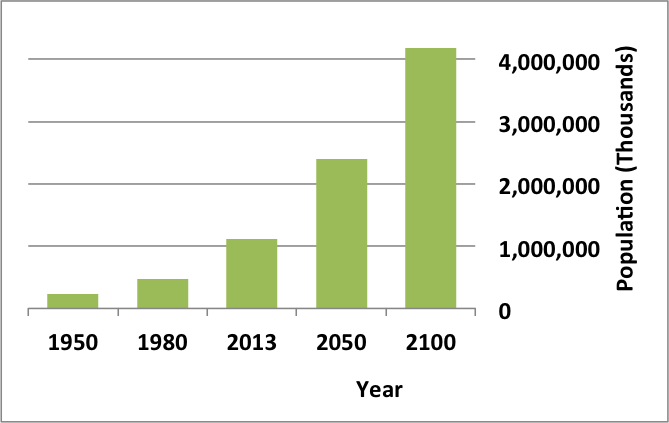

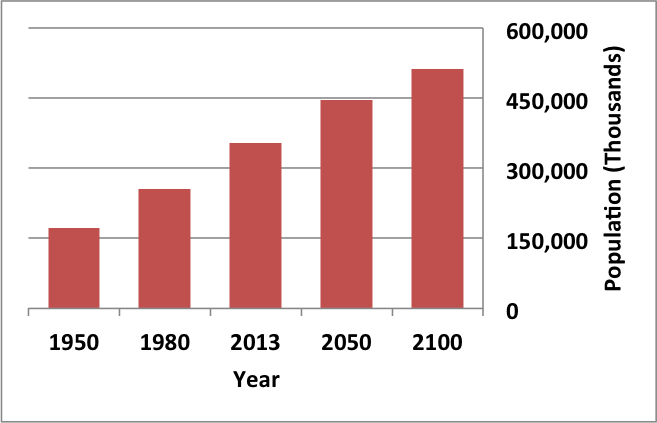

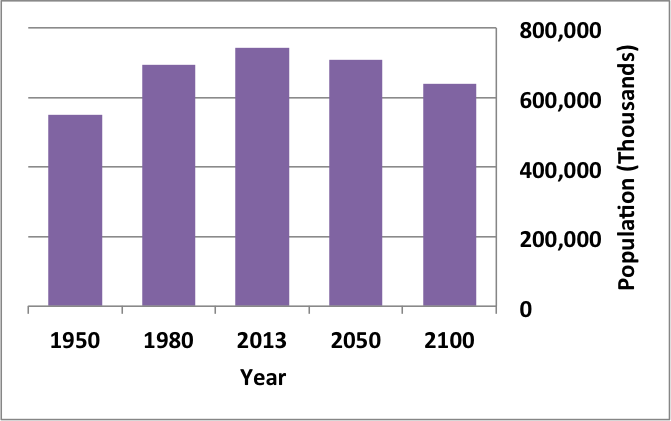

As mentioned earlier, the earth’s population is seven billion. That number might not seem particularly jarring on its own; after all, we all know there are lots of people around. But consider the fact that human population grew very slowly for most of our existence, then doubled in the span of half a century to reach six billion in 1999. And now, just over ten years later, we have added another billion. A look at the graph of projected population indicates that growth is not only going to continue, but it will continue at a rapid rate.

The United Nations Population Fund (2008) categorizes nations as high fertility, intermediate fertility, or low fertility. They anticipate the population growth to triple between 2011 and 2100 in high-fertility countries, which are currently concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa. For countries with intermediate fertility rates (the U.S., India, and Mexico all fall into this category), growth is expected to be about 26 percent. And low-fertility countries like China, Australia, and most of Europe will actually see population declines of approximately 20 percent. The graphs below illustrate this trend.

It would be impossible to discuss population growth and trends without addressing access to family planning resources and birth control. As the stages of population growth indicate, more industrialized countries see birthrates decline as families limit the number of children they have. Today, many people—over 200 million—still lack access to safe family planning, according to USAID (2010). By their report, this need is growing, with demand projected to increase by 40 percent in the next 15 years. Many social scholars would assert that until women are able to have only the children they want and can care for, the poorest countries will always bear the worst burden of overpopulation.

Scholars understand demography through various analyses. Malthusian, Zero Population Growth, Cornucopian theory, and Demographic Transition theories all help sociologists study demography. The earth’s human population is growing quickly, especially in peripheral countries. Factors that impact population include birthrates, mortality rates, and migration, including immigration and emigration. There are numerous potential outcomes of the growing population, and sociological perspectives vary on the potential effect of these increased numbers. The growth will pressure the already taxed planet and its natural resources.

The population of the planet doubled in 50 years to reach _______ in 1999?

A

A functionalist would address which issue?

B

What does carrying capacity refer to?

C

What three factors did Malthus believe would limit human population?

D

What does cornucopian theory believe?

A

Given what we know about population growth, what do you think of China’s policy that limits the number of children a family can have? Do you agree with it? Why or why not? What other ways might a country of over 1.3 billion people manage its population?

Describe the effect of immigration or emigration on your life or in a community you have seen. What are the positive effects? What are the negative effects?

Look at trends in birthrates from “Stage 4” countries (like Europe) versus those from “Stage 2” countries (like Afghanistan). How do you think these will impact global power over the next several decades? Does population equal power? Why or why not?

To learn more about population concerns, from the new-era ZPG advocates to the United Nations reports, check out these links: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/population\_connection and http://openstaxcollege.org/l/un-population

Caldwell, John Charles and Bruce Caldwell. 2006. Demographic Transition Theory. The Netherlands: Springer.

CIA World Factbook. 2011. “Guide to Country Comparisons.” Central Intelligence Agency World Factbook. Retrieved January 23, 2012 (https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/rankorderguide.html).

Ehrlich, Paul R. 1968. The Population Bomb. New York: Ballantine.

Malthus, Thomas R. 1965 [1798]. An Essay on Population. New York: Augustus Kelley.

Simon, Julian Lincoln. 1981. The Ultimate Resource. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

United Nations Population Fund. 2008. “Linking Population, Poverty, and Development.” Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://www.unfpa.org/pds/trends.htm).

USAID. 2010. “Family Planning: The World at 7 Billion.” Retrieved December 10, 2011.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1

Attribution: