Education is a social institution through which a society’s children are taught basic academic knowledge, learning skills, and cultural norms. Every nation in the world is equipped with some form of education system, though those systems vary greatly. The major factors affecting education systems are the resources and money that are utilized to support those systems in different nations. As you might expect, a country’s wealth has much to do with the amount of money spent on education. Countries that do not have such basic amenities as running water are unable to support robust education systems or, in many cases, any formal schooling at all. The result of this worldwide educational inequality is a social concern for many countries, including the United States.

International differences in education systems are not solely a financial issue. The value placed on education, the amount of time devoted to it, and the distribution of education within a country also play a role in those differences. For example, students in South Korea spend 220 days a year in school, compared to the 180 days a year of their United States counterparts (Pellissier 2010). As of 2006, the United States ranked fifth among 27 countries for college participation, but ranked 16th in the number of students who receive college degrees (National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education 2006). These statistics may be related to how much time is spent on education in the United States.

Then there is the issue of educational distribution within a nation. In December 2010, the results of a test called the Program for International Student Assessment (PISA), which is administered to 15-year-old students worldwide, were released. Those results showed that students in the United States had fallen from 15th to 25th in the rankings for science and math (National Public Radio 2010). Students at the top of the rankings hailed from Shanghai, Finland, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

Analysts determined that the nations and city-states at the top of the rankings had several things in common. For one, they had well-established standards for education with clear goals for all students. They also recruited teachers from the top 5 to 10 percent of university graduates each year, which is not the case for most countries (National Public Radio 2010).

Finally, there is the issue of social factors. One analyst from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, the organization that created the test, attributed 20 percent of performance differences and the United States’ low rankings to differences in social background. Researchers noted that educational resources, including money and quality teachers, are not distributed equitably in the United States. In the top-ranking countries, limited access to resources did not necessarily predict low performance. Analysts also noted what they described as “resilient students,” or those students who achieve at a higher level than one might expect given their social background. In Shanghai and Singapore, the proportion of resilient students is about 70 percent. In the United States, it is below 30 percent. These insights suggest that the United States’ educational system may be on a descending path that could detrimentally affect the country’s economy and its social landscape (National Public Radio 2010).

Since the fall of the Taliban in Afghanistan, there has been a spike in demand for education. This spike is so great, in fact, that it has exceeded the nation’s resources for meeting the demand. More than 6.2 million students are enrolled in grades one through 12 in Afghanistan, and about 2.2 million of those students are female (World Bank 2011). Both of these figures are the largest in Afghan history—far exceeding the time before the Taliban was in power. At the same time, there is currently a severe shortage of teachers in Afghanistan, and the educators in the system are often undertrained and frequently do not get paid on time. Currently, they are optimistic and enthusiastic about educational opportunities and approach teaching with a positive attitude, but there is fear that this optimism will not last.

With these challenges, there is a push to improve the quality of education in Afghanistan as quickly as possible. Educational leaders are looking to other post-conflict countries for guidance, hoping to learn from other nations that have faced similar circumstances. Their input suggests that the keys to rebuilding education are an early focus on quality and a commitment to educational access. Currently, educational quality in Afghanistan is generally considered poor, as is educational access. Literacy and math skills are low, as are skills in critical thinking and problem solving.

Education of females poses additional challenges since cultural norms decree that female students should be taught by female teachers. Currently, there is a lack of female teachers to meet that gender-based demand. In some provinces, the female student population falls below 15 percent of students (World Bank 2011). Female education is also important to Afghanistan’s future because mothers are primary socialization agents: an educated mother is more likely to instill a thirst for education in her children, setting up a positive cycle of education for generations to come.

Improvements must be made to Afghanistan’s infrastructure in order to improve education, which has historically been managed at the local level. The World Bank, which strives to help developing countries break free of poverty and become self-sustaining has been hard at work to assist the people of Afghanistan in improving educational quality and access. The Education Quality Improvement Program provides training for teachers and grants to communities. The program is active in all 34 provinces of Afghanistan, supporting grants for both quality enhancement and development of infrastructure as well as providing a teacher education program.

Another program called Strengthening Higher Education focuses on six universities in Afghanistan and four regional colleges. The emphasis of this program is on fostering relationships with universities in other countries, including the United States and India, to focus on fields including engineering, natural sciences, and English as a second language. The program also seeks to improve libraries and laboratories through grants.

These efforts by the World Bank illustrate the ways global attention and support can benefit an educational system. In developing countries like Afghanistan, partnerships with countries that have established successful educational programs play a key role in efforts to rebuild their future.

As already mentioned, education is not solely concerned with the basic academic concepts that a student learns in the classroom. Societies also educate their children, outside of the school system, in matters of everyday practical living. These two types of learning are referred to as formal education and informal education.

Formal education describes the learning of academic facts and concepts through a formal curriculum. Arising from the tutelage of ancient Greek thinkers, centuries of scholars have examined topics through formalized methods of learning. Education in earlier times was only available to the higher classes; they had the means for access to scholarly materials, plus the luxury of leisure time that could be used for learning. The Industrial Revolution and its accompanying social changes made education more accessible to the general population. Many families in the emerging middle class found new opportunities for schooling.

The modern U.S. educational system is the result of this progression. Today, basic education is considered a right and responsibility for all citizens. Expectations of this system focus on formal education, with curricula and testing designed to ensure that students learn the facts and concepts that society believes are basic knowledge.

In contrast, informal education describes learning about cultural values, norms, and expected behaviors by participating in a society. This type of learning occurs both through the formal education system and at home. Our earliest learning experiences generally happen via parents, relatives, and others in our community. Through informal education, we learn how to dress for different occasions, how to perform regular life routines like shopping for and preparing food, and how to keep our bodies clean.

Cultural transmission refers to the way people come to learn the values, beliefs, and social norms of their culture. Both informal and formal education include cultural transmission. For example, a student will learn about cultural aspects of modern history in a U.S. History classroom. In that same classroom, the student might learn the cultural norm for asking a classmate out on a date through passing notes and whispered conversations.

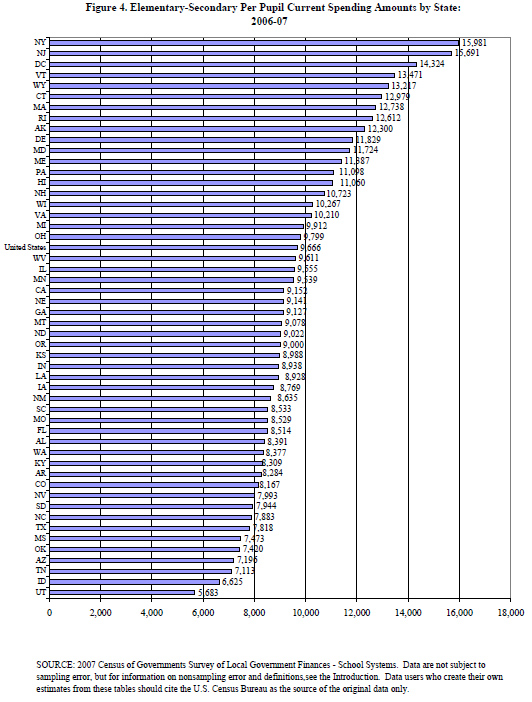

Another global concern in education is universal access. This term refers to people’s equal ability to participate in an education system. On a world level, access might be more difficult for certain groups based on class or gender (as was the case in the United States earlier in our nation’s history, a dynamic we still struggle to overcome). The modern idea of universal access arose in the United States as a concern for people with disabilities. In the United States, one way in which universal education is supported is through federal and state governments covering the cost of free public education. Of course, the way this plays out in terms of school budgets and taxes makes this an often-contested topic on the national, state, and community levels.

A precedent for universal access to education in the United States was set with the 1972 U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia’s decision in Mills v. Board of Education of the District of Columbia. This case was brought on the behalf of seven school-age children with special needs who argued that the school board was denying their access to free public education. The school board maintained that the children’s “exceptional” needs, which included mental retardation and mental illness, precluded their right to be educated for free in a public school setting. The board argued that the cost of educating these children would be too expensive and that the children would therefore have to remain at home without access to education.

This case was resolved in a hearing without any trial. The judge, Joseph Cornelius Waddy, upheld the students’ right to education, finding that they were to be given either public education services or private education paid for by the Washington, D.C., board of education. He noted that

Constitutional rights must be afforded citizens despite the greater expense involved … the District of Columbia’s interest in educating the excluded children clearly must outweigh its interest in preserving its financial resources. … The inadequacies of the District of Columbia Public School System whether occasioned by insufficient funding or administrative inefficiency, certainly cannot be permitted to bear more heavily on the “exceptional” or handicapped child than on the normal child (Mills v. Board of Education 1972).

Today, the optimal way to include differently able students in standard classrooms is still being researched and debated. “Inclusion” is a method that involves complete immersion in a standard classroom, whereas “mainstreaming” balances time in a special-needs classroom with standard classroom participation. There continues to be social debate surrounding how to implement the ideal of universal access to education.

Educational systems around the world have many differences, though the same factors—including resources and money—affect every educational system. Educational distribution is a major issue in many nations, including in the United States, where the amount of money spent per student varies greatly by state. Education happens through both formal and informal systems; both foster cultural transmission. Universal access to education is a worldwide concern.

What are the major factors affecting education systems throughout the world?

A

What do nations that are top-ranked in science and math have in common?

B

Informal education _________________.

B

Learning from classmates that most students buy lunch on Fridays is an example of ________.

A

The 1972 case Mills v. Board of Education of the District of Columbia set a precedent for __________.

A

Has there ever been a time when your formal and informal educations in the same setting were at odds? How did you overcome that disconnect?

Do you believe free access to schools has achieved its intended goal? Explain.

Though it’s a struggle, education is continually being improved in the developing world. To learn how educational programs are being fostered worldwide, explore the Education section of the Center for Global Development’s website: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/center\_global\_development

Durkheim, Emile. 1898 [1956]. Education and Sociology. New York: Free Press.

Mills v. Board of Education, 348 DC 866 (1972).

National Center for Public Policy and Higher Education. 2006. Measuring UP: The National Report Card on Higher Education. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (http://www.eric.ed.gov/PDFS/ED493360.pdf).

National Public Radio. 2010. “Study Confirms U.S. Falling Behind in Education.” All Things Considered, December 10. Retrieved December 9, 2011 (https://www.npr.org/2010/12/07/131884477/Study-Confirms-U-S-Falling-Behind-In-Education).

Pellissier, Hank. 2010. “High Test Scores, Higher Expectations, and Presidential Hype.” Great Schools. Retrieved January 17, 2012 (http://www.greatschools.org/students/academic-skills/2427-South-Korean-schools.gs).

Rampell, Catherine. 2009. “Of All States, New York’s Schools Spend Most Money Per Pupil.” Economix. Retrieved December 15, 2011 (http://economix.blogs.nytimes.com/2009/07/27/of-all-states-new-york-schools-spend-most-money-per-pupil/).

U.S. Census Bureau. 2009. “Public Education Finances 2007.” Retrieved April 26, 2012 (http://www2.census.gov/govs/school/07f33pub.pdf).

World Bank. 2011. “Education in Afghanistan.” Retrieved December 14, 2011 (http://go.worldbank.org/80UMV47QB0).

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1

Attribution: