Technology and the media are interwoven, and neither can be separated from contemporary society in most core and semi-peripheral nations. Media is a term that refers to all print, digital, and electronic means of communication. From the time the printing press was created (and even before), technology has influenced how and where information is shared. Today, it is impossible to discuss media and the ways that societies communicate without addressing the fast-moving pace of technology. Twenty years ago, if you wanted to share news of your baby’s birth or a job promotion, you phoned or wrote letters. You might tell a handful of people, but probably you wouldn’t call up several hundred, including your old high school chemistry teacher, to let them know. Now, by tweeting or posting your big news, the circle of communication is wider than ever. Therefore, when we talk about how societies engage with technology we must take media into account, and vice versa.

Technology creates media. The comic book you bought your daughter at the drugstore is a form of media, as is the movie you rented for family night, the internet site you used to order dinner online, the billboard you passed on the way to get that dinner, and the newspaper you read while you were waiting to pick up your order. Without technology, media would not exist; but remember, technology is more than just the media we are exposed to.

There is no one way of dividing technology into categories. Whereas once it might have been simple to classify innovations such as machine-based or drug-based or the like, the interconnected strands of technological development mean that advancement in one area might be replicated in dozens of others. For simplicity’s sake, we will look at how the U.S. Patent Office, which receives patent applications for nearly all major innovations worldwide, addresses patents. This regulatory body will patent three types of innovation. Utility patents are the first type. These are granted for the invention or discovery of any new and useful process, product, or machine, or for a significant improvement to existing technologies. The second type of patent is a design patent. Commonly conferred in architecture and industrial design, this means someone has invented a new and original design for a manufactured product. Plant patents, the final type, recognize the discovery of new plant types that can be asexually reproduced. While genetically modified food is the hot-button issue within this category, farmers have long been creating new hybrids and patenting them. A more modern example might be food giant Monsanto, which patents corn with built-in pesticide (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office 2011).

Anderson and Tushman (1990) suggest an evolutionary model of technological change, in which a breakthrough in one form of technology leads to a number of variations. Once those are assessed, a prototype emerges, and then a period of slight adjustments to the technology, interrupted by a breakthrough. For example, floppy disks were improved and upgraded, then replaced by Zip disks, which were in turn improved to the limits of the technology and were then replaced by flash drives. This is essentially a generational model for categorizing technology, in which first-generation technology is a relatively unsophisticated jumping-off point leading to an improved second generation, and so on.

Media and technology have evolved hand in hand, from early print to modern publications, from radio to television to film. New media emerge constantly, such as we see in the online world.

Early forms of print media, found in ancient Rome, were hand-copied onto boards and carried around to keep the citizenry informed. With the invention of the printing press, the way that people shared ideas changed, as information could be mass produced and stored. For the first time, there was a way to spread knowledge and information more efficiently; many credit this development as leading to the Renaissance and ultimately the Age of Enlightenment. This is not to say that newspapers of old were more trustworthy than the Weekly World News and National Enquirer are today. Sensationalism abounded, as did censorship that forbade any subjects that would incite the populace.

The invention of the telegraph, in the mid-1800s, changed print media almost as much as the printing press. Suddenly information could be transmitted in minutes. As the 19th century became the 20th, American publishers such as Hearst redefined the world of print media and wielded an enormous amount of power to socially construct national and world events. Of course, even as the media empires of William Randolph Hearst and Joseph Pulitzer were growing, print media also allowed for the dissemination of countercultural or revolutionary materials. Internationally, Vladimir Lenin’s Irksa (The Spark) newspaper was published in 1900 and played a role in Russia’s growing communist movement (World Association of Newspapers 2004).

With the invention and widespread use of television in the mid-20th century, newspaper circulation steadily dropped off, and in the 21st century, circulation has dropped further as more people turn to internet news sites and other forms of new media to stay informed. According to the Pew Research Center, 2009 saw an unprecedented drop in newspaper circulation––down 10.6 percent from the year before (Pew 2010).

This shift away from newspapers as a source of information has profound effects on societies. When the news is given to a large diverse conglomerate of people, it must (to appeal to them and keep them subscribing) maintain some level of broad-based reporting and balance. As newspapers decline, news sources become more fractured, so that the audience can choose specifically what it wants to hear and what it wants to avoid.

Radio programming obviously preceded television, but both shaped people’s lives in much the same way. In both cases, information (and entertainment) could be enjoyed at home, with a kind of immediacy and community that newspapers could not offer. For instance, many older Americans might remember when they heard on the radio that Pearl Harbor had been bombed, or when they saw on the television that President John F. Kennedy had been shot. Even though people were in their own homes, media allowed them to share these moments in real time. This same kind of separate-but-communal approach occurred with entertainment too. School-aged children and office workers gathered to discuss the previous night’s installment of a serial television or radio show.

Right up through the 1970s, American television was dominated by three major networks (ABC, CBS, and NBC) that competed for ratings and advertising dollars. They also exerted a lot of control over what was being watched. Public television, in contrast, offered an educational nonprofit alternative to the sensationalization of news spurred by the network competition for viewers and advertising dollars. Those sources—PBS (Public Broadcasting Service), the BBC (British Broadcasting Company), and CBC (Canadian Broadcasting Company)—garnered a worldwide reputation for quality programming and a global perspective. Al Jazeera, the Arabic independent news station, has joined this group as a similar media force that broadcasts to people worldwide.

The impact of television on American society is hard to overstate. By the late 1990s, 98 percent of U.S. homes had at least one television set, and the average American watched between two and a half to five hours of television daily. All this television has a powerful socializing effect, with these forms of visual media providing reference groups while reinforcing social norms, values, and beliefs.

The film industry took off in the 1930s, when color and sound were first integrated into feature films. Like television, early films were unifying for society: As people gathered in theaters to watch new releases, they would laugh, cry, and be scared together. Movies also act as time capsules or cultural touchstones for society. From tough-talking Clint Eastwood to the biopic of Facebook founder and Harvard dropout Mark Zuckerberg, movies illustrate society’s dreams, fears, and experiences. While many Americans consider Hollywood the epicenter of moviemaking, India’s Bollywood actually produces more films per year, speaking to the cultural aspirations and norms of Indian society.

New media encompasses all interactive forms of information exchange. These include social networking sites, blogs, podcasts, wikis, and virtual worlds. Clearly, the list grows almost daily. New media tends to level the playing field in terms of who is constructing it, i.e., creating, publishing, distributing, and accessing information (Lievrouw and Livingston 2006), as well as offering alternative forums to groups unable to gain access to traditional political platforms, such as groups associated with the Arab Spring protests (van de Donk et al. 2004). However, there is no guarantee of the accuracy of the information offered. In fact, the immediacy of new media coupled with the lack of oversight means that we must be more careful than ever to ensure our news is coming from accurate sources.

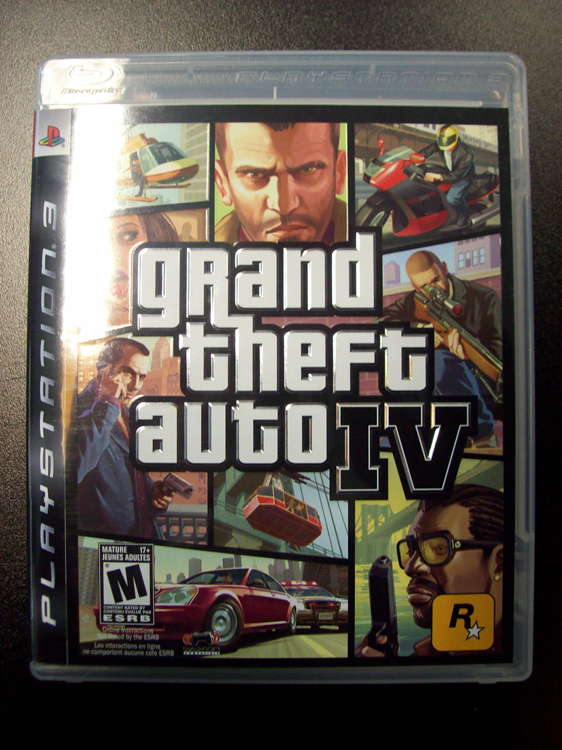

A glance through popular video game and movie titles geared toward children and teens shows the vast spectrum of violence that is displayed, condoned, and acted out. It may hearken back to Popeye and Bluto beating up on each other, or Wile E. Coyote trying to kill and devour the Road Runner, but the graphics and actions have moved far beyond Acme’s cartoon dynamite.

As a way to guide parents in their programming choices, the motion picture industry put a rating system in place in the 1960s. But new media—video games in particular—proved to be uncharted territory. In 1994, the Entertainment Software Rating Board (ERSB) set a ratings system for games that addressed issues of violence, sexuality, drug use, and the like. California took it a step further by making it illegal to sell video games to underage buyers. The case led to a heated debate about personal freedoms and child protection, and in 2011, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled against the California law, stating it violated freedom of speech (ProCon 2012).

Children’s play has often involved games of aggression—from cowboys and Indians, to cops and robbers, to water-balloon fights. Many articles report on the controversy surrounding the linkage between violent video games and violent behavior. Are these charges true? Psychologists Anderson and Bushman (2001) reviewed 40-plus years of research on the subject and, in 2003, determined that there are causal linkages between violent video game use and aggression. They found that children who had just played a violent video game demonstrated an immediate increase in hostile or aggressive thoughts, an increase in aggressive emotions, and physiological arousal that increased the chances of acting out aggressive behavior (Anderson 2003).

Ultimately, repeated exposure to this kind of violence leads to increased expectations regarding violence as a solution, increased violent behavioral scripts, and making violent behavior more cognitively accessible (Anderson 2003). In short, people who play a lot of these games find it easier to imagine and access violent solutions than nonviolent ones, and are less socialized to see violence as a negative. While these facts do not mean there is no role for video games, it should give players pause. Clearly, when it comes to violence in gaming, it’s not “only a game.”

Can You Hear Me Now? I’m Lovin’ It. The Verizon Halftime Report. Companies use advertising to sell to us, but the way they reach us is changing. Increasingly, synergistic advertising practices ensure you are receiving the same message from a variety of sources. For example, you may see billboards for Miller on your way to a stadium, sit down to watch a game preceded by an MGD commercial on the big screen, and watch a halftime ad in which people are frequently shown holding up the trademark bottles. Chances are you can guess which brand of beer is for sale at the concession stand.

Advertising has changed, as technology and media have allowed consumers to bypass traditional advertising venues. From the invention of the remote control, which allows us to ignore television advertising without leaving our seats, to recording devices that let us watch television programs but skip the ads, conventional advertising is on the wane. And print media is no different. Advertising revenue in newspapers and on television fell significantly in 2009, showing that companies need new ways of getting their message to consumers.

One model companies are considering to address this advertising downturn uses the same philosophy as celebrity endorsements, just on a different scale. Companies are hiring college students to be their on-campus representatives, looking for popular students involved in high-profile activities like sports, fraternities, and music. The marketing team is betting that if we buy perfume because Beyoncé tells us to, we’ll also choose our cell phone or smoothie if a popular student encourages that brand. According to an article in the New York Times, fall semester 2011 saw an estimated 10,000 American college students working on campus as brand ambassadors for products from Red Bull energy drinks to Hewlett-Packard computers (Singer 2011). As the companies figure it, college students will trust one source of information above all: other students.

Despite the variety of media at hand, the mainstream news and entertainment you enjoy are increasingly homogenized. Research by McManus (1995) suggests that different news outlets all tell the same stories, using the same sources, resulting in the same message, presented with only slight variations. So whether you are reading the New York Times or the CNN’s web site, the coverage of national events like a major court case or political issue will likely be the same.

Simultaneous to this homogenization among the major news outlets, the opposite process is occurring in the newer media streams. With so many choices, people increasingly “customize” their news experience, minimizing “chance encounters” with information that does not jive with their worldview (Prior 2005). For instance, those who are staunchly Republican can avoid centrist or liberal-leaning cable news shows and web sites that would show Democrats in a favorable light. They know to seek out Fox News over MSNBC, just as Democrats know to do the opposite. Further, people who want to avoid politics completely can choose to visit web sites that deal only with entertainment or that will keep them up to date on sports scores. They have an easy way to avoid information they do not wish to hear.

Media and technology have been interwoven from the earliest days of human communication. The printing press, the telegraph, and the internet are all examples of their intersection. Mass media has allowed for more shared social experiences, but new media now creates a seemingly endless amount of airtime for any and every voice that wants to be heard. Advertising has also changed with technology. New media allows consumers to bypass traditional advertising venues, causing companies to be more innovative and intrusive as they try to gain our attention.

When it comes to technology, media, and society, which of the following is true?

C

If the U.S. Patent Office were to issue a patent for a new type of tomato that tastes like a jellybean, it would be issuing a _________ patent?

B

Which of the following is the primary component of the evolutionary model of technological change?

D

Which of the following is not a form of new media?

A

Research regarding video game violence suggests that _________.

D

Comic books, Wikipedia, MTV, and a commercial for Coca-Cola are all examples of:

A

Where and how do you get your news? Do you watch network television? Read the newspaper? Go online? How about your parents or grandparents? Do you think it matters where you seek out information? Why or why not?

Do you believe new media allows for the kind of unifying moments that television and radio programming used to? If so, give an example.

Where are you most likely to notice advertisements? What causes them to catch your attention?

To get a sense of the timeline of technology, check out this web site: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/Tech\_History

To learn more about new media, click here: http://openstaxcollege.org/l/new\_media

Anderson, C.A., and B.J. Bushman. 2001. “Effects of Violent Video Games on Aggressive Behavior, Aggressive Cognition, Aggressive Affect, Physiological Arousal, and Prosocial Behavior: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Scientific Literature.” Psychological Science 12:353–359.

Anderson, Craig. 2003. “Violent Video Games: Myths, Facts and Unanswered Questions.” American Psychological Association, October. Retrieved January 13, 2012 (http://www.apa.org/science/about/psa/2003/10/anderson.aspx).

Anderson, Philip and Michael Tushman. 1990. “Technological Discontinuities and Dominant Designs: A Cyclical Model of Technological Change.” Administrative Science Quarterly 35:604–633.

Lievrouw, Leah A. and Sonia Livingstone, eds. 2006. Handbook of New Media: Social Shaping and Social Consequences. London : SAGE Publications.

McManus, John. 1995. “A Market-Based Model of News Production.” Communication Theory 5:301–338.

Pew Research Center. 2010. “State of the News Media 2010.” Pew Research Center Publications, March 15. Retrieved January 24, 2012 ( [link] ).

Prior, Markus. 2005. “News vs. Entertainment: How Increasing Media Choice Widens Gaps in Political Knowledge and Turnout.” American Journal of Political Science 49(3):577–592.

ProCon. 2012. “Video Games.” January 5. Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://videogames.procon.org/).

Singer, Natasha. 2011. “On Campus, It’s One Big Commercial.” New York Times, September 10. Retrieved February 10, 2012 (http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/11/business/at-colleges-the-marketers-are-everywhere.html?pagewanted=1&\_r=1&ref=education).

United States Patent and Trademark Office. 2012. “General Information Concerning Patents.” Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.uspto.gov/patents/resources/general\_info\_concerning\_patents.jsphttp://www.uspto.gov/patents/resources/general\_info\_concerning\_patents.jsp).

van de Donk, W., B.D. Loader, P.G. Nixon, and D. Rucht, eds. 2004. Cyberprotest: New Media, Citizens, and Social Movements. New York: Routledge.

World Association of Newspapers. 2004. “Newspapers: A Brief History.” Retrieved January 12, 2012 (http://www.wan-press.org/article.php3?id\_article=2821).

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1

Attribution: