{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

{:}

Since ancient times, people have been fascinated by the relationship between individuals and the societies to which they belong. Many of the topics that are central to modern sociological scholarship were studied by ancient philosophers. Many of these earlier thinkers were motivated by their desire to describe an ideal society.

In the 13th century, Ma Tuan-Lin, a Chinese historian, first recognized social dynamics as an underlying component of historical development in his seminal encyclopedia, General Study of Literary Remains. The next century saw the emergence of the historian some consider to be the world’s first sociologist: Ibn Khaldun (1332–1406) of Tunisia. He wrote about many topics of interest today, setting a foundation for both modern sociology and economics, including a theory of social conflict, a comparison of nomadic and sedentary life, a description of political economy, and a study connecting a tribe’s social cohesion to its capacity for power (Hannoum 2003).

In the 18th century, Age of Enlightenment philosophers developed general principles that could be used to explain social life. Thinkers such as John Locke, Voltaire, Immanuel Kant, and Thomas Hobbes responded to what they saw as social ills by writing on topics that they hoped would lead to social reform.

The early 19th century saw great changes with the Industrial Revolution, increased mobility, and new kinds of employment. It was also a time of great social and political upheaval with the rise of empires that exposed many people—for the first time—to societies and cultures other than their own. Millions of people were moving into cities and many people were turning away from their traditional religious beliefs.

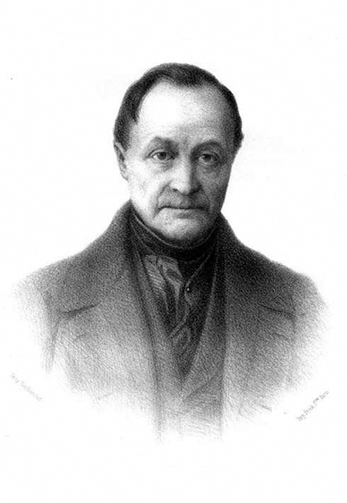

The term sociology was first coined in 1780 by the French essayist Emmanuel-Joseph Sieyès (1748–1836) in an unpublished manuscript (Fauré et al. 1999). In 1838, the term was reinvented by Auguste Comte (1798–1857). Comte originally studied to be an engineer, but later became a pupil of social philosopher Claude Henri de Rouvroy Comte de Saint-Simon (1760–1825). They both thought that society could be studied using the same scientific methods utilized in natural sciences. Comte also believed in the potential of social scientists to work toward the betterment of society. He held that once scholars identified the laws that governed society, sociologists could address problems such as poor education and poverty (Abercrombie et al. 2000).

Comte named the scientific study of social patterns positivism. He described his philosophy in a series of books called The Course in Positive Philosophy (1830–1842) and A General View of Positivism (1848). He believed that using scientific methods to reveal the laws by which societies and individuals interact would usher in a new “positivist” age of history. While the field and its terminology have grown, sociologists still believe in the positive impact of their work.

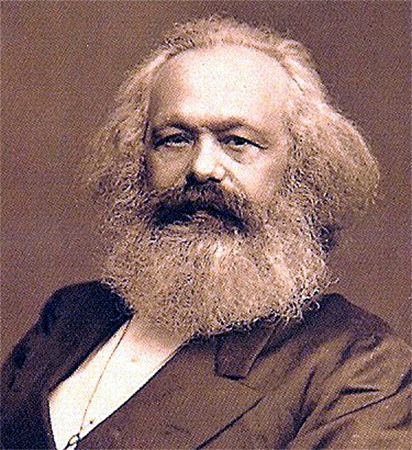

Karl Marx (1818–1883) was a German philosopher and economist. In 1848 he and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) coauthored the Communist Manifesto. This book is one of the most influential political manuscripts in history. It also presents Marx's theory of society, which differed from what Comte proposed.

Marx rejected Comte's positivism. He believed that societies grew and changed as a result of the struggles of different social classes over the means of production. At the time he was developing his theories, the Industrial Revolution and the rise of capitalism led to great disparities in wealth between the owners of the factories and workers. Capitalism, an economic system characterized by private or corporate ownership of goods and the means to produce them, grew in many nations.

Marx predicted that inequalities of capitalism would become so extreme that workers would eventually revolt. This would lead to the collapse of capitalism, which would be replaced by communism. Communism is an economic system under which there is no private or corporate ownership: everything is owned communally and distributed as needed. Marx believed that communism was a more equitable system than capitalism.

While his economic predictions may not have come true in the time frame he predicted, Marx’s idea that social conflict leads to change in society is still one of the major theories used in modern sociology.

In 1873, the English philosopher Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) published The Study of Sociology, the first book with the term “sociology” in the title. Spencer rejected much of Comte’s philosophy as well as Marx's theory of class struggle and his support of communism. Instead, he favored a form of government that allowed market forces to control capitalism. His work influenced many early sociologists including Émile Durkheim (1858–1917).

Durkheim helped establish sociology as a formal academic discipline by establishing the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux in 1895 and by publishing his Rules of the Sociological Method in 1895. In another important work, Division of Labour in Society (1893), Durkheim laid out his theory on how societies transformed from a primitive state into a capitalist, industrial society. According to Durkheim, people rise to their proper level in society based on merit.

Durkheim believed that sociologists could study objective “social facts” (Poggi 2000). He also believed that through such studies it would be possible to determine if a society was “healthy” or “pathological.” He saw healthy societies as stable, while pathological societies experienced a breakdown in social norms between individuals and society.

In 1897, Durkheim attempted to demonstrate the effectiveness of his rules of social research when he published a work titled Suicide. Durkheim examined suicide statistics in different police districts to research differences between Catholic and Protestant communities. He attributed the differences to socioreligious forces rather than to individual or psychological causes.

Prominent sociologist Max Weber (1864–1920) established a sociology department in Germany at the Ludwig Maximilians University of Munich in 1919. Weber wrote on many topics related to sociology including political change in Russia and social forces that affect factory workers. He is known best for his 1904 book, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. The theory that Weber sets forth in this book is still controversial. Some believe that Weber was arguing that the beliefs of many Protestants, especially Calvinists, led to the creation of capitalism. Others interpret it as simply claiming that the ideologies of capitalism and Protestantism are complementary.

Weber also made a major contribution to the methodology of sociological research. Along with other researchers such as Wilhelm Dilthey (1833–1911) and Heinrich Rickert (1863–1936), Weber believed that it was difficult if not impossible to use standard scientific methods to accurately predict the behavior of groups as people hoped to do. They argued that the influence of culture on human behavior had to be taken into account. This even applied to the researchers themselves, who, they believed, should be aware of how their own cultural biases could influence their research. To deal with this problem, Weber and Dilthey introduced the concept of verstehen, a German word that means to understand in a deep way. In seeking verstehen, outside observers of a social world—an entire culture or a small setting—attempt to understand it from an insider’s point of view.

In his book The Nature of Social Action (1922), Weber described sociology as striving to "interpret the meaning of social action and thereby give a causal explanation of the way in which action proceeds and the effects it produces." He and other like-minded sociologists proposed a philosophy of antipositivism whereby social researchers would strive for subjectivity as they worked to represent social processes, cultural norms, and societal values. This approach led to some research methods whose aim was not to generalize or predict (traditional in science), but to systematically gain an in-depth understanding of social worlds.

The different approaches to research based on positivism or antipositivism are often considered the foundation for the differences found today between quantitative sociology and qualitative sociology. Quantitative sociology uses statistical methods such as surveys with large numbers of participants. Researchers analyze data using statistical techniques to see if they can uncover patterns of human behavior. Qualitative sociology seeks to understand human behavior by learning about it through in-depth interviews, focus groups, and analysis of content sources (like books, magazines, journals, and popular media).

What constitutes a “typical family” in America has changed tremendously over the past decades. One of the most notable changes has been the increasing number of mothers who work outside the home. Earlier in U.S. society, most family households consisted of one parent working outside the home and the other being the primary childcare provider. Because of traditional gender roles and family structures, this was typically a working father and a stay-at-home mom. Quantitative research shows that in 1940 only 27 percent of all women worked outside the home. Today, 59.2 percent of all women do. Almost half of women with children younger than one year of age are employed (U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee Report 2010).

Sociologists interested in this topic might approach its study from a variety of angles. One might be interested in its impact on a child’s development, another may explore related economic values, while a third might examine how other social institutions have responded to this shift in society.

A sociologist studying the impact of working mothers on a child’s development might ask questions about children raised in childcare settings. How is a child socialized differently when raised largely by a childcare provider rather than a parent? Do early experiences in a school-like childcare setting lead to improved academic performance later in life? How does a child with two working parents perceive gender roles compared to a child raised with a stay-at-home parent?

Another sociologist might be interested in the increase in working mothers from an economic perspective. Why do so many households today have dual incomes? Has there been a contributing change in social class expectations? What impact does the larger economy play in the economic conditions of an individual household? Do people view money—savings, spending, debt—differently than they have in the past?

Curiosity about this trend’s influence on social institutions might lead a researcher to explore its effect on the nation’s educational system. Has the increase in working mothers shifted traditional family responsibilities onto schools, such as providing lunch and even breakfast for students? How does the creation of after-school care programs shift resources away from traditional academics?

As these examples show, sociologists study many real-world topics. Their research often influences social policies and political issues. Results from sociological studies on this topic might play a role in developing federal laws like the Family and Medical Leave Act, or they might bolster the efforts of an advocacy group striving to reduce social stigmas placed on stay-at-home dads, or they might help governments determine how to best allocate funding for education.

Sociology was developed as a way to study and try to understand the changes to society brought on by the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries. Some of the earliest sociologists thought that societies and individuals’ roles in society could be studied using the same scientific methodologies that were used in the natural sciences, while others believed that is was impossible to predict human behavior scientifically, and still others debated the value of such predictions. Those perspectives continue to be represented within sociology today.

Which of the following was a topic of study in early sociology?

B

Which founder of sociology believed societies changed due to class struggle?

B

The difference between positivism and antipositivism relates to:

C

Which would a quantitative sociologists use to gather data?

A

Weber believed humans could not be studied purely objectively because they were influenced by:

B

What do you make of Karl Marx’s contributions to sociology? What perceptions of Marx have you been exposed to in your society, and how do those perceptions influence your views?

Do you tend to place more value on qualitative or quantitative research? Why? Does it matter what topic is being studied?

Many sociologists helped shape the discipline. To learn more about prominent sociologists and how they changed sociology check out http://openstaxcollege.org/l/ferdinand-toennies.

Abercrombie, Nicholas, Stephen Hill, and Bryan S. Turner. 2000. The Penguin Dictionary of Sociology. London: Penguin.

Durkheim, Émile. 1964 [1895]. The Rules of Sociological Method, edited by J. Mueller, E. George and E. Caitlin. 8th ed. Translated by S. Solovay. New York: Free Press.

Fauré, Christine, Jacques Guilhaumou, Jacques Vallier, and Françoise Weil. 2007 [1999]. Des Manuscrits de Sieyès, 1773–1799, Volumes I and II. Paris: Champion.

Hannoum, Abdelmajid. 2003. Translation and the Colonial Imaginary: Ibn Khaldun Orientalist. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (http://www.jstor.org/pss/3590803).

Poggi, Gianfranco. 2000. Durkheim. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

U.S. Congress Joint Economic Committee. 2010. Women and the Economy, 2010: 25 Years of Progress But Challenges Remain. August. Washington, DC: Congressional Printing Office. Retrieved January 19, 2012 (http://jec.senate.gov/public/?a=Files.Serve&File\_id=8be22cb0-8ed0-4a1a-841b-aa91dc55fa81).

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/02040312-72c8-441e-a685-20e9333f3e1d@10.1

Attribution: