Before looking at all the particles we now know about, let us examine some of the machines that created them. The fundamental process in creating previously unknown particles is to accelerate known particles, such as protons or electrons, and direct a beam of them toward a target. Collisions with target nuclei provide a wealth of information, such as information obtained by Rutherford using energetic helium nuclei from natural

radiation. But if the energy of the incoming particles is large enough, new matter is sometimes created in the collision. The more energy input or

, the more matter

can be created, since

. Limitations are placed on what can occur by known conservation laws, such as conservation of mass-energy, momentum, and charge. Even more interesting are the unknown limitations provided by nature. Some expected reactions do occur, while others do not, and still other unexpected reactions may appear. New laws are revealed, and the vast majority of what we know about particle physics has come from accelerator laboratories. It is the particle physicist’s favorite indoor sport, which is partly inspired by theory.

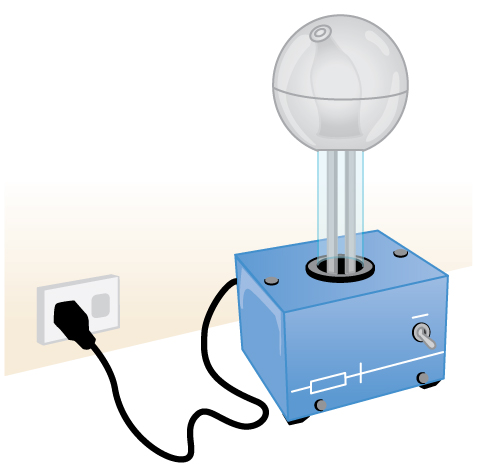

An early accelerator is a relatively simple, large-scale version of the electron gun. The Van de Graaff (named after the Dutch physicist), which you have likely seen in physics demonstrations, is a small version of the ones used for nuclear research since their invention for that purpose in 1932. For more, see [link]. These machines are electrostatic, creating potentials as great as 50 MV, and are used to accelerate a variety of nuclei for a range of experiments. Energies produced by Van de Graaffs are insufficient to produce new particles, but they have been instrumental in exploring several aspects of the nucleus. Another, equally famous, early accelerator is the cyclotron, invented in 1930 by the American physicist, E. O. Lawrence (1901–1958). For a visual representation with more detail, see [link]. Cyclotrons use fixed-frequency alternating electric fields to accelerate particles. The particles spiral outward in a magnetic field, making increasingly larger radius orbits during acceleration. This clever arrangement allows the successive addition of electric potential energy and so greater particle energies are possible than in a Van de Graaff. Lawrence was involved in many early discoveries and in the promotion of physics programs in American universities. He was awarded the 1939 Nobel Prize in Physics for the cyclotron and nuclear activations, and he has an element and two major laboratories named for him.

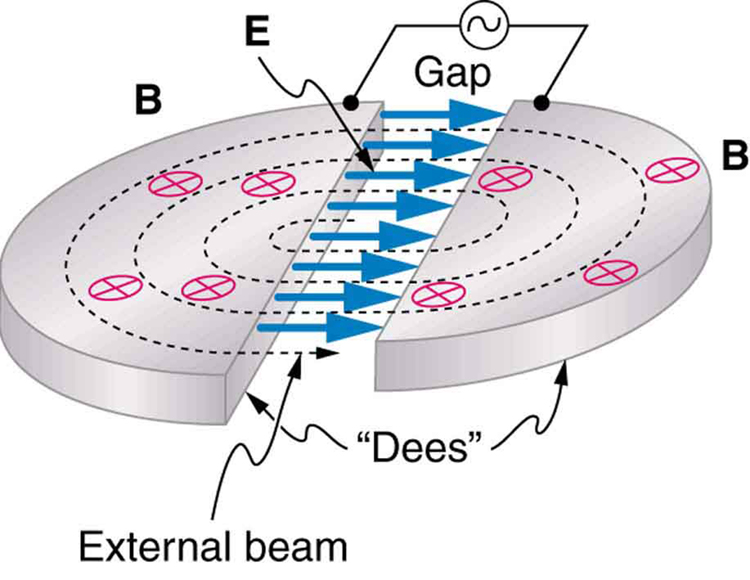

A synchrotron is a version of a cyclotron in which the frequency of the alternating voltage and the magnetic field strength are increased as the beam particles are accelerated. Particles are made to travel the same distance in a shorter time with each cycle in fixed-radius orbits. A ring of magnets and accelerating tubes, as shown in [link], are the major components of synchrotrons. Accelerating voltages are synchronized (i.e., occur at the same time) with the particles to accelerate them, hence the name. Magnetic field strength is increased to keep the orbital radius constant as energy increases. High-energy particles require strong magnetic fields to steer them, so superconducting magnets are commonly employed. Still limited by achievable magnetic field strengths, synchrotrons need to be very large at very high energies, since the radius of a high-energy particle’s orbit is very large. Radiation caused by a magnetic field accelerating a charged particle perpendicular to its velocity is called synchrotron radiation in honor of its importance in these machines. Synchrotron radiation has a characteristic spectrum and polarization, and can be recognized in cosmic rays, implying large-scale magnetic fields acting on energetic and charged particles in deep space. Synchrotron radiation produced by accelerators is sometimes used as a source of intense energetic electromagnetic radiation for research purposes.

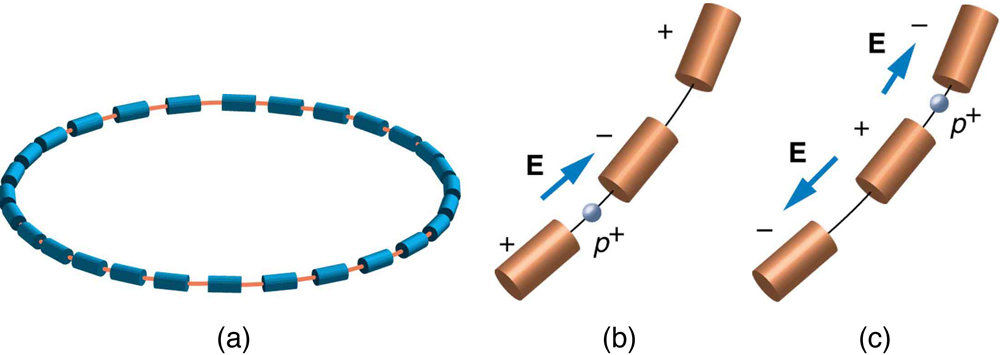

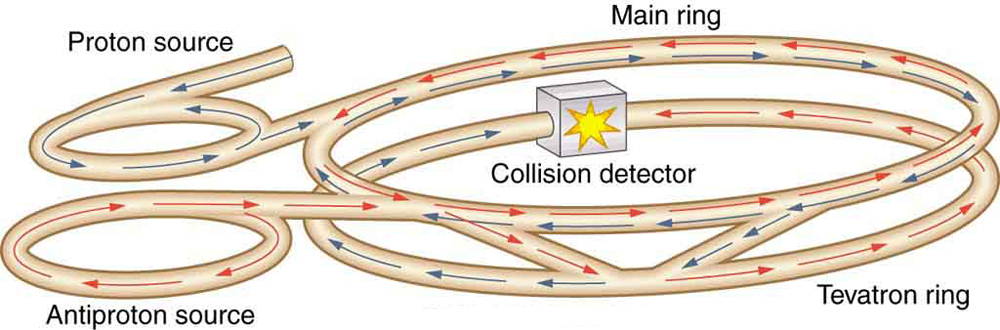

Physicists have built ever-larger machines, first to reduce the wavelength of the probe and obtain greater detail, then to put greater energy into collisions to create new particles. Each major energy increase brought new information, sometimes producing spectacular progress, motivating the next step. One major innovation was driven by the desire to create more massive particles. Since momentum needs to be conserved in a collision, the particles created by a beam hitting a stationary target should recoil. This means that part of the energy input goes into recoil kinetic energy, significantly limiting the fraction of the beam energy that can be converted into new particles. One solution to this problem is to have head-on collisions between particles moving in opposite directions. Colliding beams are made to meet head-on at points where massive detectors are located. Since the total incoming momentum is zero, it is possible to create particles with momenta and kinetic energies near zero. Particles with masses equivalent to twice the beam energy can thus be created. Another innovation is to create the antimatter counterpart of the beam particle, which thus has the opposite charge and circulates in the opposite direction in the same beam pipe. For a schematic representation, see [link].

Detectors capable of finding the new particles in the spray of material that emerges from colliding beams are as impressive as the accelerators. While the Fermilab Tevatron had proton and antiproton beam energies of about 1 TeV, so that it can create particles up to

, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC) at the European Center for Nuclear Research (CERN) has achieved beam energies of 3.5 TeV, so that it has a 7-TeV collision energy; CERN hopes to double the beam energy in 2014. The now-canceled Superconducting Super Collider was being constructed in Texas with a design energy of 20 TeV to give a 40-TeV collision energy. It was to be an oval 30 km in diameter. Its cost as well as the politics of international research funding led to its demise.

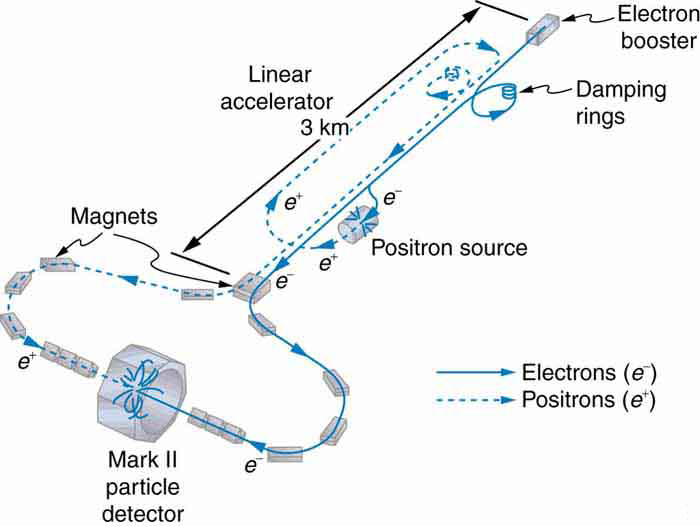

In addition to the large synchrotrons that produce colliding beams of protons and antiprotons, there are other large electron-positron accelerators. The oldest of these was a straight-line or linear accelerator, called the Stanford Linear Accelerator (SLAC), which accelerated particles up to 50 GeV as seen in [link]. Positrons created by the accelerator were brought to the same energy and collided with electrons in specially designed detectors. Linear accelerators use accelerating tubes similar to those in synchrotrons, but aligned in a straight line. This helps eliminate synchrotron radiation losses, which are particularly severe for electrons made to follow curved paths. CERN had an electron-positron collider appropriately called the Large Electron-Positron Collider (LEP), which accelerated particles to 100 GeV and created a collision energy of 200 GeV. It was 8.5 km in diameter, while the SLAC machine was 3.2 km long.

A linear accelerator designed to produce a beam of 800-MeV protons has 2000 accelerating tubes. What average voltage must be applied between tubes (such as in the gaps in [link]) to achieve the desired energy?

Strategy

The energy given to the proton in each gap between tubes is

where

is the proton’s charge and

is the potential difference (voltage) across the gap. Since

and

, the proton gains 1 eV in energy for each volt across the gap that it passes through. The AC voltage applied to the tubes is timed so that it adds to the energy in each gap. The effective voltage is the sum of the gap voltages and equals 800 MV to give each proton an energy of 800 MeV.

Solution

There are 2000 gaps and the sum of the voltages across them is 800 MV; thus,

Discussion

A voltage of this magnitude is not difficult to achieve in a vacuum. Much larger gap voltages would be required for higher energy, such as those at the 50-GeV SLAC facility. Synchrotrons are aided by the circular path of the accelerated particles, which can orbit many times, effectively multiplying the number of accelerations by the number of orbits. This makes it possible to reach energies greater than 1 TeV.

The total energy in the beam of an accelerator is far greater than the energy of the individual beam particles. Why isn’t this total energy available to create a single extremely massive particle?

Synchrotron radiation takes energy from an accelerator beam and is related to acceleration. Why would you expect the problem to be more severe for electron accelerators than proton accelerators?

What two major limitations prevent us from building high-energy accelerators that are physically small?

What are the advantages of colliding-beam accelerators? What are the disadvantages?

At full energy, protons in the 2.00-km-diameter Fermilab synchrotron travel at nearly the speed of light, since their energy is about 1000 times their rest mass energy.

(a) How long does it take for a proton to complete one trip around?

(b) How many times per second will it pass through the target area?

(a)

(b)

Suppose a

created in a bubble chamber lives for

What distance does it move in this time if it is traveling at 0.900 c? Since this distance is too short to make a track, the presence of the

must be inferred from its decay products. Note that the time is longer than the given

lifetime, which can be due to the statistical nature of decay or time dilation.

What length track does a

traveling at 0.100 c leave in a bubble chamber if it is created there and lives for

? (Those moving faster or living longer may escape the detector before decaying.)

78.0 cm

The 3.20-km-long SLAC produces a beam of 50.0-GeV electrons. If there are 15,000 accelerating tubes, what average voltage must be across the gaps between them to achieve this energy?

Because of energy loss due to synchrotron radiation in the LHC at CERN, only 5.00 MeV is added to the energy of each proton during each revolution around the main ring. How many revolutions are needed to produce 7.00-TeV (7000 GeV) protons, if they are injected with an initial energy of 8.00 GeV?

A proton and an antiproton collide head-on, with each having a kinetic energy of 7.00 TeV (such as in the LHC at CERN). How much collision energy is available, taking into account the annihilation of the two masses? (Note that this is not significantly greater than the extremely relativistic kinetic energy.)

When an electron and positron collide at the SLAC facility, they each have 50.0 GeV kinetic energies. What is the total collision energy available, taking into account the annihilation energy? Note that the annihilation energy is insignificant, because the electrons are highly relativistic.

100 GeV

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@11.1

Attribution: