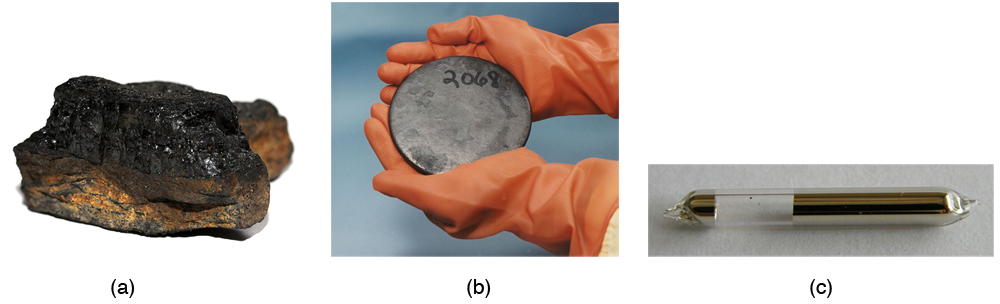

What is inside the nucleus? Why are some nuclei stable while others decay? (See [link].) Why are there different types of decay (

,

and

)? Why are nuclear decay energies so large? Pursuing natural questions like these has led to far more fundamental discoveries than you might imagine.

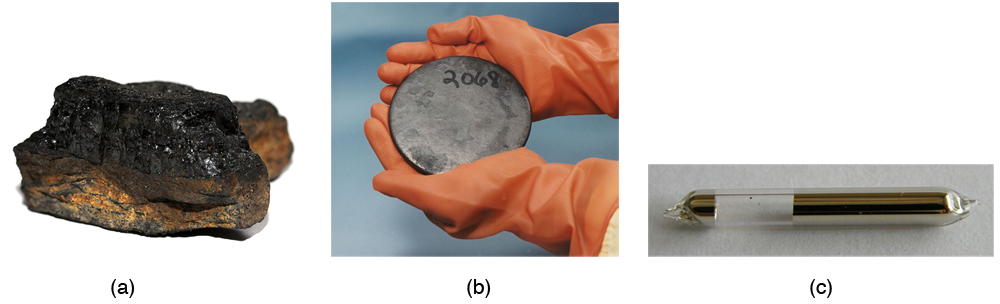

We have already identified protons as the particles that carry positive charge in the nuclei. However, there are actually two types of particles in the nuclei—the proton and the neutron, referred to collectively as nucleons, the constituents of nuclei. As its name implies, the neutron is a neutral particle (

) that has nearly the same mass and intrinsic spin as the proton. [link] compares the masses of protons, neutrons, and electrons. Note how close the proton and neutron masses are, but the neutron is slightly more massive once you look past the third digit. Both nucleons are much more massive than an electron. In fact,

(as noted in Medical Applications of Nuclear Physics and

.

[link] also gives masses in terms of mass units that are more convenient than kilograms on the atomic and nuclear scale. The first of these is the unified atomic mass unit (u), defined as

This unit is defined so that a neutral carbon

atom has a mass of exactly 12 u. Masses are also expressed in units of

. These units are very convenient when considering the conversion of mass into energy (and vice versa), as is so prominent in nuclear processes. Using

and units of

in

, we find that

cancels and

comes out conveniently in MeV. For example, if the rest mass of a proton is converted entirely into energy, then

It is useful to note that 1 u of mass converted to energy produces 931.5 MeV, or

All properties of a nucleus are determined by the number of protons and neutrons it has. A specific combination of protons and neutrons is called a nuclide and is a unique nucleus. The following notation is used to represent a particular nuclide:

where the symbols

,

,

, and

are defined as follows: The number of protons in a nucleus is the atomic number

, as defined in Medical Applications of Nuclear Physics. X is the symbol for the element, such as Ca for calcium. However, once

is known, the element is known; hence,

and

are redundant. For example,

is always calcium, and calcium always has

.

is the number of neutrons in a nucleus. In the notation for a nuclide, the subscript

is usually omitted. The symbol

is defined as the number of nucleons or the total number of protons and neutrons,

where

is also called the mass number. This name for

is logical; the mass of an atom is nearly equal to the mass of its nucleus, since electrons have so little mass. The mass of the nucleus turns out to be nearly equal to the sum of the masses of the protons and neutrons in it, which is proportional to

. In this context, it is particularly convenient to express masses in units of u. Both protons and neutrons have masses close to 1 u, and so the mass of an atom is close to

u. For example, in an oxygen nucleus with eight protons and eight neutrons,

, and its mass is 16 u. As noticed, the unified atomic mass unit is defined so that a neutral carbon atom (actually a

atom) has a mass of exactly 12

. Carbon was chosen as the standard, partly because of its importance in organic chemistry (see Appendix A).

| Particle | Symbol | kg | u | MeVc2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Proton | p | 1.007276 | 938.27 | |

| Neutron | n | 1.008665 | 939.57 | |

| Electron | e | 0.00054858 | 0.511 |

Let us look at a few examples of nuclides expressed in the

notation. The nucleus of the simplest atom, hydrogen, is a single proton, or

(the zero for no neutrons is often omitted). To check this symbol, refer to the periodic table—you see that the atomic number

of hydrogen is 1. Since you are given that there are no neutrons, the mass number

is also 1. Suppose you are told that the helium nucleus or

particle has two protons and two neutrons. You can then see that it is written

. There is a scarce form of hydrogen found in nature called deuterium; its nucleus has one proton and one neutron and, hence, twice the mass of common hydrogen. The symbol for deuterium is, thus,

(sometimes

is used, as for deuterated water

). An even rarer—and radioactive—form of hydrogen is called tritium, since it has a single proton and two neutrons, and it is written

. These three varieties of hydrogen have nearly identical chemistries, but the nuclei differ greatly in mass, stability, and other characteristics. Nuclei (such as those of hydrogen) having the same

and different

s are defined to be isotopes of the same element.

There is some redundancy in the symbols

,

,

, and

. If the element

is known, then

can be found in a periodic table and is always the same for a given element. If both

and

are known, then

can also be determined (first find

; then,

). Thus the simpler notation for nuclides is

which is sufficient and is most commonly used. For example, in this simpler notation, the three isotopes of hydrogen are

and

while the

particle is

. We read this backward, saying helium-4 for

, or uranium-238 for

. So for

, should we need to know, we can determine that

for uranium from the periodic table, and, thus,

.

A variety of experiments indicate that a nucleus behaves something like a tightly packed ball of nucleons, as illustrated in [link]. These nucleons have large kinetic energies and, thus, move rapidly in very close contact. Nucleons can be separated by a large force, such as in a collision with another nucleus, but resist strongly being pushed closer together. The most compelling evidence that nucleons are closely packed in a nucleus is that the radius of a nucleus,

, is found to be given approximately by

where

and

is the mass number of the nucleus. Note that

. Since many nuclei are spherical, and the volume of a sphere is

, we see that

—that is, the volume of a nucleus is proportional to the number of nucleons in it. This is what would happen if you pack nucleons so closely that there is no empty space between them.

Nucleons are held together by nuclear forces and resist both being pulled apart and pushed inside one another. The volume of the nucleus is the sum of the volumes of the nucleons in it, here shown in different colors to represent protons and neutrons.

(a) Find the radius of an iron-56 nucleus. (b) Find its approximate density in

, approximating the mass of

to be 56 u.

Strategy and Concept

(a) Finding the radius of

is a straightforward application of

given

. (b) To find the approximate density, we assume the nucleus is spherical (this one actually is), calculate its volume using the radius found in part (a), and then find its density from

. Finally, we will need to convert density from units of

to

.

Solution

(a) The radius of a nucleus is given by

Substituting the values for

and

yields

(b) Density is defined to be

, which for a sphere of radius

is

Substituting known values gives

Converting to units of

, we find

Discussion

(a) The radius of this medium-sized nucleus is found to be approximately 4.6 fm, and so its diameter is about 10 fm, or

. In our discussion of Rutherford’s discovery of the nucleus, we noticed that it is about

in diameter (which is for lighter nuclei), consistent with this result to an order of magnitude. The nucleus is much smaller in diameter than the typical atom, which has a diameter of the order of

.

(b) The density found here is so large as to cause disbelief. It is consistent with earlier discussions we have had about the nucleus being very small and containing nearly all of the mass of the atom. Nuclear densities, such as found here, are about

times greater than that of water, which has a density of “only”

. One cubic meter of nuclear matter, such as found in a neutron star, has the same mass as a cube of water 61 km on a side.

What forces hold a nucleus together? The nucleus is very small and its protons, being positive, exert tremendous repulsive forces on one another. (The Coulomb force increases as charges get closer, since it is proportional to

, even at the tiny distances found in nuclei.) The answer is that two previously unknown forces hold the nucleus together and make it into a tightly packed ball of nucleons. These forces are called the weak and strong nuclear forces. Nuclear forces are so short ranged that they fall to zero strength when nucleons are separated by only a few fm. However, like glue, they are strongly attracted when the nucleons get close to one another. The strong nuclear force is about 100 times more attractive than the repulsive EM force, easily holding the nucleons together. Nuclear forces become extremely repulsive if the nucleons get too close, making nucleons strongly resist being pushed inside one another, something like ball bearings.

The fact that nuclear forces are very strong is responsible for the very large energies emitted in nuclear decay. During decay, the forces do work, and since work is force times the distance (

), a large force can result in a large emitted energy. In fact, we know that there are two distinct nuclear forces because of the different types of nuclear decay—the strong nuclear force is responsible for

decay, while the weak nuclear force is responsible for

decay.

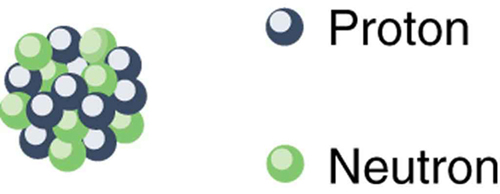

The many stable and unstable nuclei we have explored, and the hundreds we have not discussed, can be arranged in a table called the chart of the nuclides, a simplified version of which is shown in [link]. Nuclides are located on a plot of

versus

. Examination of a detailed chart of the nuclides reveals patterns in the characteristics of nuclei, such as stability, abundance, and types of decay, analogous to but more complex than the systematics in the periodic table of the elements.

In principle, a nucleus can have any combination of protons and neutrons, but [link] shows a definite pattern for those that are stable. For low-mass nuclei, there is a strong tendency for

and

to be nearly equal. This means that the nuclear force is more attractive when

. More detailed examination reveals greater stability when

and

are even numbers—nuclear forces are more attractive when neutrons and protons are in pairs. For increasingly higher masses, there are progressively more neutrons than protons in stable nuclei. This is due to the ever-growing repulsion between protons. Since nuclear forces are short ranged, and the Coulomb force is long ranged, an excess of neutrons keeps the protons a little farther apart, reducing Coulomb repulsion. Decay modes of nuclides out of the region of stability consistently produce nuclides closer to the region of stability. There are more stable nuclei having certain numbers of protons and neutrons, called magic numbers. Magic numbers indicate a shell structure for the nucleus in which closed shells are more stable. Nuclear shell theory has been very successful in explaining nuclear energy levels, nuclear decay, and the greater stability of nuclei with closed shells. We have been producing ever-heavier transuranic elements since the early 1940s, and we have now produced the element with

. There are theoretical predictions of an island of relative stability for nuclei with such high

s.

is the number of protons or atomic number, X is the symbol for the element,

is the number of neutrons, and

is the mass number or the total number of protons and neutrons,

but different

are isotopes of the same element.

, is approximately

where

. Nuclear volumes are proportional to

. There are two nuclear forces, the weak and the strong. Systematics in nuclear stability seen on the chart of the nuclides indicate that there are shell closures in nuclei for values of

and

equal to the magic numbers, which correspond to highly stable nuclei.

The weak and strong nuclear forces are basic to the structure of matter. Why we do not experience them directly?

Define and make clear distinctions between the terms neutron, nucleon, nucleus, nuclide, and neutrino.

What are isotopes? Why do different isotopes of the same element have similar chemistries?

Verify that a

mass of water at normal density would make a cube 60 km on a side, as claimed in [link]. (This mass at nuclear density would make a cube 1.0 m on a side.)

Find the length of a side of a cube having a mass of 1.0 kg and the density of nuclear matter, taking this to be

.

What is the radius of an

particle?

Find the radius of a

nucleus.

is a manufactured nuclide that is used as a power source on some space probes.

(a) Calculate the radius of

, one of the most tightly bound stable nuclei.

(b) What is the ratio of the radius of

to that of

, one of the largest nuclei ever made? Note that the radius of the largest nucleus is still much smaller than the size of an atom.

(a)

(b)

The unified atomic mass unit is defined to be

. Verify that this amount of mass converted to energy yields 931.5 MeV. Note that you must use four-digit or better values for

and

.

What is the ratio of the velocity of a

particle to that of an

particle, if they have the same nonrelativistic kinetic energy?

If a 1.50-cm-thick piece of lead can absorb 90.0% of the

rays from a radioactive source, how many centimeters of lead are needed to absorb all but 0.100% of the

rays?

The detail observable using a probe is limited by its wavelength. Calculate the energy of a

-ray photon that has a wavelength of

, small enough to detect details about one-tenth the size of a nucleon. Note that a photon having this energy is difficult to produce and interacts poorly with the nucleus, limiting the practicability of this probe.

(a) Show that if you assume the average nucleus is spherical with a radius

, and with a mass of

u, then its density is independent of

.

(b) Calculate that density in

and

, and compare your results with those found in [link] for

.

What is the ratio of the velocity of a 5.00-MeV

ray to that of an

particle with the same kinetic energy? This should confirm that

s travel much faster than

s even when relativity is taken into consideration. (See also [link].)

19.3 to 1

(a) What is the kinetic energy in MeV of a

ray that is traveling at

? This gives some idea of how energetic a

ray must be to travel at nearly the same speed as a

ray. (b) What is the velocity of the

ray relative to the

ray?

and different

s

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@11.1

Attribution: