Standard measurements of voltage and current alter the circuit being measured, introducing uncertainties in the measurements. Voltmeters draw some extra current, whereas ammeters reduce current flow. Null measurements balance voltages so that there is no current flowing through the measuring device and, therefore, no alteration of the circuit being measured.

Null measurements are generally more accurate but are also more complex than the use of standard voltmeters and ammeters, and they still have limits to their precision. In this module, we shall consider a few specific types of null measurements, because they are common and interesting, and they further illuminate principles of electric circuits.

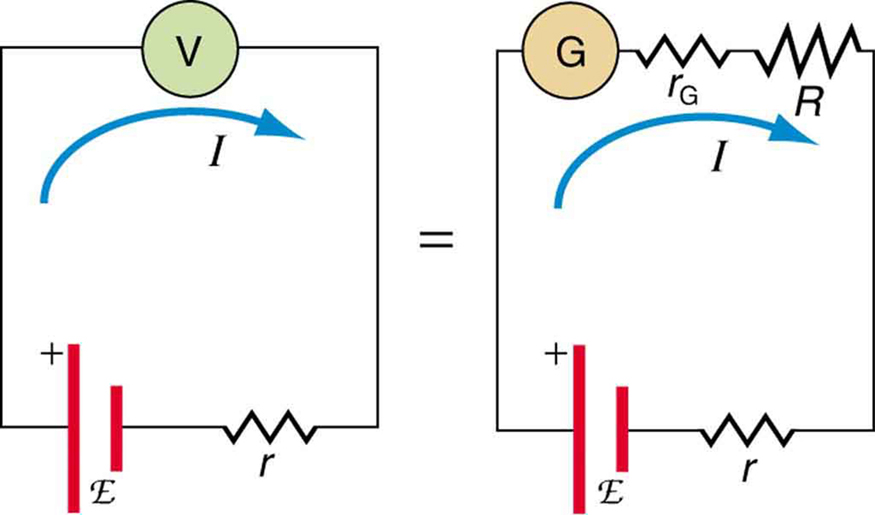

Suppose you wish to measure the emf of a battery. Consider what happens if you connect the battery directly to a standard voltmeter as shown in [link]. (Once we note the problems with this measurement, we will examine a null measurement that improves accuracy.) As discussed before, the actual quantity measured is the terminal voltage

, which is related to the emf of the battery by

, where

is the current that flows and

is the internal resistance of the battery.

The emf could be accurately calculated if

were very accurately known, but it is usually not. If the current

could be made zero, then

, and so emf could be directly measured. However, standard voltmeters need a current to operate; thus, another technique is needed.

A potentiometer is a null measurement device for measuring potentials (voltages). (See [link].) A voltage source is connected to a resistor

say, a long wire, and passes a constant current through it. There is a steady drop in potential (an

drop) along the wire, so that a variable potential can be obtained by making contact at varying locations along the wire.

[link](b) shows an unknown

(represented by script

in the figure) connected in series with a galvanometer. Note that

opposes the other voltage source. The location of the contact point (see the arrow on the drawing) is adjusted until the galvanometer reads zero. When the galvanometer reads zero,

, where

is the resistance of the section of wire up to the contact point. Since no current flows through the galvanometer, none flows through the unknown emf, and so

is directly sensed.

Now, a very precisely known standard

is substituted for

, and the contact point is adjusted until the galvanometer again reads zero, so that

. In both cases, no current passes through the galvanometer, and so the current

through the long wire is the same. Upon taking the ratio

,

cancels, giving

Solving for

gives

Because a long uniform wire is used for

, the ratio of resistances

is the same as the ratio of the lengths of wire that zero the galvanometer for each emf. The three quantities on the right-hand side of the equation are now known or measured, and

can be calculated. The uncertainty in this calculation can be considerably smaller than when using a voltmeter directly, but it is not zero. There is always some uncertainty in the ratio of resistances

and in the standard

. Furthermore, it is not possible to tell when the galvanometer reads exactly zero, which introduces error into both

and

, and may also affect the current

.

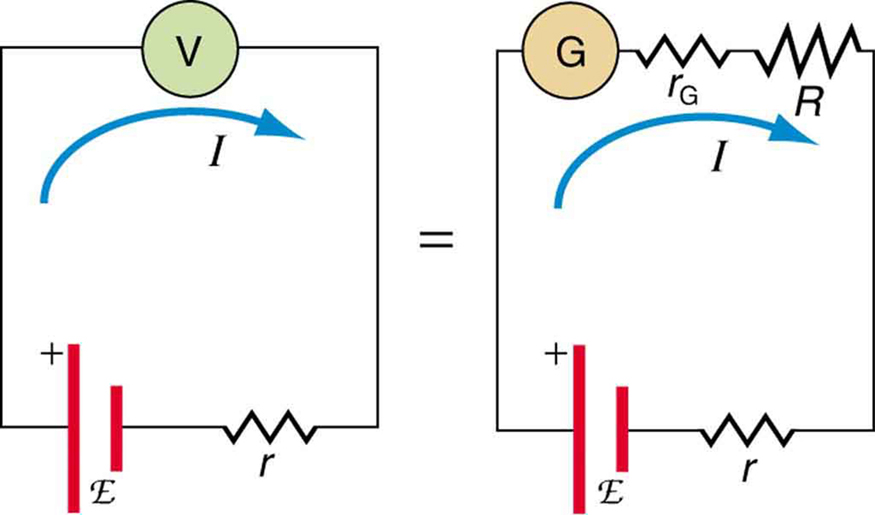

There is a variety of so-called ohmmeters that purport to measure resistance. What the most common ohmmeters actually do is to apply a voltage to a resistance, measure the current, and calculate the resistance using Ohm’s law. Their readout is this calculated resistance. Two configurations for ohmmeters using standard voltmeters and ammeters are shown in [link]. Such configurations are limited in accuracy, because the meters alter both the voltage applied to the resistor and the current that flows through it.

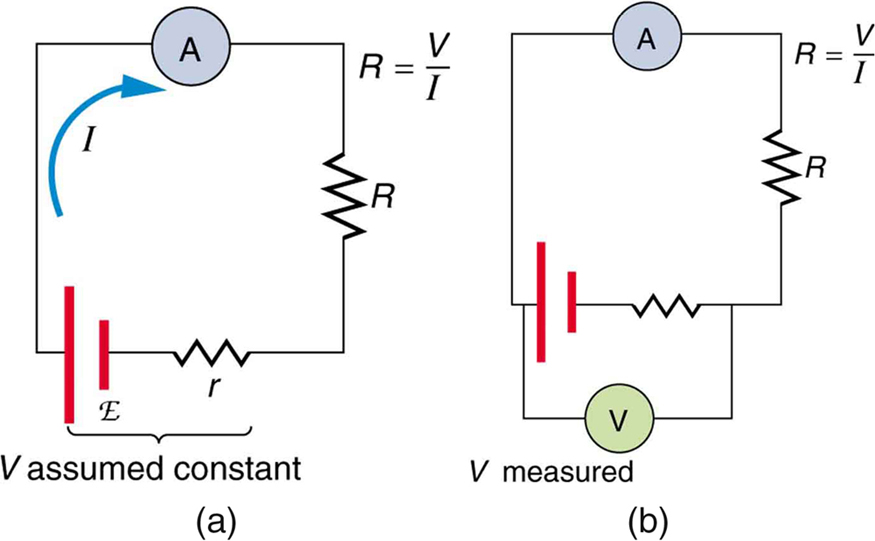

The Wheatstone bridge is a null measurement device for calculating resistance by balancing potential drops in a circuit. (See [link].) The device is called a bridge because the galvanometer forms a bridge between two branches. A variety of bridge devices are used to make null measurements in circuits.

Resistors

and

are precisely known, while the arrow through

indicates that it is a variable resistance. The value of

can be precisely read. With the unknown resistance

in the circuit,

is adjusted until the galvanometer reads zero. The potential difference between points b and d is then zero, meaning that b and d are at the same potential. With no current running through the galvanometer, it has no effect on the rest of the circuit. So the branches abc and adc are in parallel, and each branch has the full voltage of the source. That is, the

drops along abc and adc are the same. Since b and d are at the same potential, the

drop along ad must equal the

drop along ab. Thus,

Again, since b and d are at the same potential, the

drop along dc must equal the

drop along bc. Thus,

Taking the ratio of these last two expressions gives

Canceling the currents and solving for Rx yields

This equation is used to calculate the unknown resistance when current through the galvanometer is zero. This method can be very accurate (often to four significant digits), but it is limited by two factors. First, it is not possible to get the current through the galvanometer to be exactly zero. Second, there are always uncertainties in

,

, and

, which contribute to the uncertainty in

.

Identify other factors that might limit the accuracy of null measurements. Would the use of a digital device that is more sensitive than a galvanometer improve the accuracy of null measurements?

One factor would be resistance in the wires and connections in a null measurement. These are impossible to make zero, and they can change over time. Another factor would be temperature variations in resistance, which can be reduced but not completely eliminated by choice of material. Digital devices sensitive to smaller currents than analog devices do improve the accuracy of null measurements because they allow you to get the current closer to zero.

Why can a null measurement be more accurate than one using standard voltmeters and ammeters? What factors limit the accuracy of null measurements?

If a potentiometer is used to measure cell emfs on the order of a few volts, why is it most accurate for the standard

to be the same order of magnitude and the resistances to be in the range of a few ohms?

What is the

of a cell being measured in a potentiometer, if the standard cell’s emf is 12.0 V and the potentiometer balances for

and

?

24.0 V

Calculate the

of a dry cell for which a potentiometer is balanced when

, while an alkaline standard cell with an emf of 1.600 V requires

to balance the potentiometer.

When an unknown resistance

is placed in a Wheatstone bridge, it is possible to balance the bridge by adjusting

to be

. What is

if

?

To what value must you adjust

to balance a Wheatstone bridge, if the unknown resistance

is

,

is

, and

is

?

(a) What is the unknown

in a potentiometer that balances when

is

, and balances when

is

for a standard 3.000-V emf? (b) The same

is placed in the same potentiometer, which now balances when

is

for a standard emf of 3.100 V. At what resistance

will the potentiometer balance?

(a) 2.00 V

(b)

Suppose you want to measure resistances in the range from

to

using a Wheatstone bridge that has

. Over what range should

be adjustable?

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@11.1

Attribution: