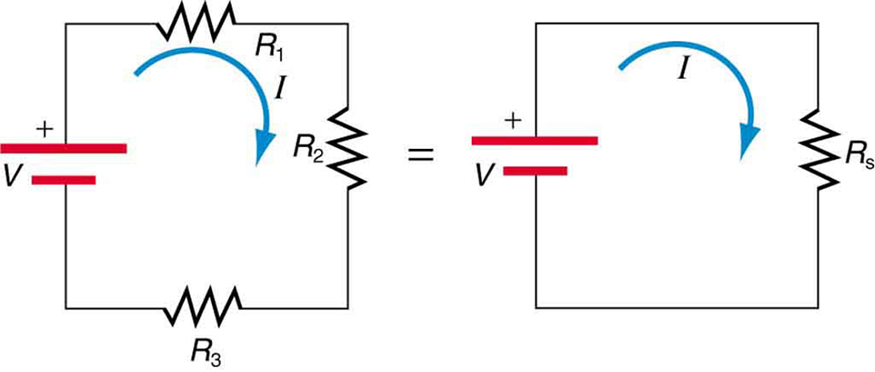

Most circuits have more than one component, called a resistor that limits the flow of charge in the circuit. A measure of this limit on charge flow is called resistance. The simplest combinations of resistors are the series and parallel connections illustrated in [link]. The total resistance of a combination of resistors depends on both their individual values and how they are connected.

When are resistors in series? Resistors are in series whenever the flow of charge, called the current, must flow through devices sequentially. For example, if current flows through a person holding a screwdriver and into the Earth, then

in [link](a) could be the resistance of the screwdriver’s shaft,

the resistance of its handle,

the person’s body resistance, and

the resistance of her shoes.

[link] shows resistors in series connected to a voltage source. It seems reasonable that the total resistance is the sum of the individual resistances, considering that the current has to pass through each resistor in sequence. (This fact would be an advantage to a person wishing to avoid an electrical shock, who could reduce the current by wearing high-resistance rubber-soled shoes. It could be a disadvantage if one of the resistances were a faulty high-resistance cord to an appliance that would reduce the operating current.)

To verify that resistances in series do indeed add, let us consider the loss of electrical power, called a voltage drop, in each resistor in [link].

According to Ohm’s law, the voltage drop,

, across a resistor when a current flows through it is calculated using the equation

, where

equals the current in amps (A) and

is the resistance in ohms

. Another way to think of this is that

is the voltage necessary to make a current

flow through a resistance

.

So the voltage drop across

is

, that across

is

, and that across

is

. The sum of these voltages equals the voltage output of the source; that is,

This equation is based on the conservation of energy and conservation of charge. Electrical potential energy can be described by the equation

, where

is the electric charge and

is the voltage. Thus the energy supplied by the source is

, while that dissipated by the resistors is

The derivations of the expressions for series and parallel resistance are based on the laws of conservation of energy and conservation of charge, which state that total charge and total energy are constant in any process. These two laws are directly involved in all electrical phenomena and will be invoked repeatedly to explain both specific effects and the general behavior of electricity.

These energies must be equal, because there is no other source and no other destination for energy in the circuit. Thus,

. The charge

cancels, yielding

, as stated. (Note that the same amount of charge passes through the battery and each resistor in a given amount of time, since there is no capacitance to store charge, there is no place for charge to leak, and charge is conserved.)

Now substituting the values for the individual voltages gives

Note that for the equivalent single series resistance

, we have

This implies that the total or equivalent series resistance

of three resistors is

.

This logic is valid in general for any number of resistors in series; thus, the total resistance

of a series connection is

as proposed. Since all of the current must pass through each resistor, it experiences the resistance of each, and resistances in series simply add up.

Suppose the voltage output of the battery in [link] is

, and the resistances are

,

, and

. (a) What is the total resistance? (b) Find the current. (c) Calculate the voltage drop in each resistor, and show these add to equal the voltage output of the source. (d) Calculate the power dissipated by each resistor. (e) Find the power output of the source, and show that it equals the total power dissipated by the resistors.

Strategy and Solution for (a)

The total resistance is simply the sum of the individual resistances, as given by this equation:

Strategy and Solution for (b)

The current is found using Ohm’s law,

. Entering the value of the applied voltage and the total resistance yields the current for the circuit:

Strategy and Solution for (c)

The voltage—or

drop—in a resistor is given by Ohm’s law. Entering the current and the value of the first resistance yields

Similarly,

and

Discussion for (c)

The three

drops add to

, as predicted:

Strategy and Solution for (d)

The easiest way to calculate power in watts (W) dissipated by a resistor in a DC circuit is to use Joule’s law,

, where

is electric power. In this case, each resistor has the same full current flowing through it. By substituting Ohm’s law

into Joule’s law, we get the power dissipated by the first resistor as

Similarly,

and

Discussion for (d)

Power can also be calculated using either

or

, where

is the voltage drop across the resistor (not the full voltage of the source). The same values will be obtained.

Strategy and Solution for (e)

The easiest way to calculate power output of the source is to use

, where

is the source voltage. This gives

Discussion for (e)

Note, coincidentally, that the total power dissipated by the resistors is also 7.20 W, the same as the power put out by the source. That is,

Power is energy per unit time (watts), and so conservation of energy requires the power output of the source to be equal to the total power dissipated by the resistors.

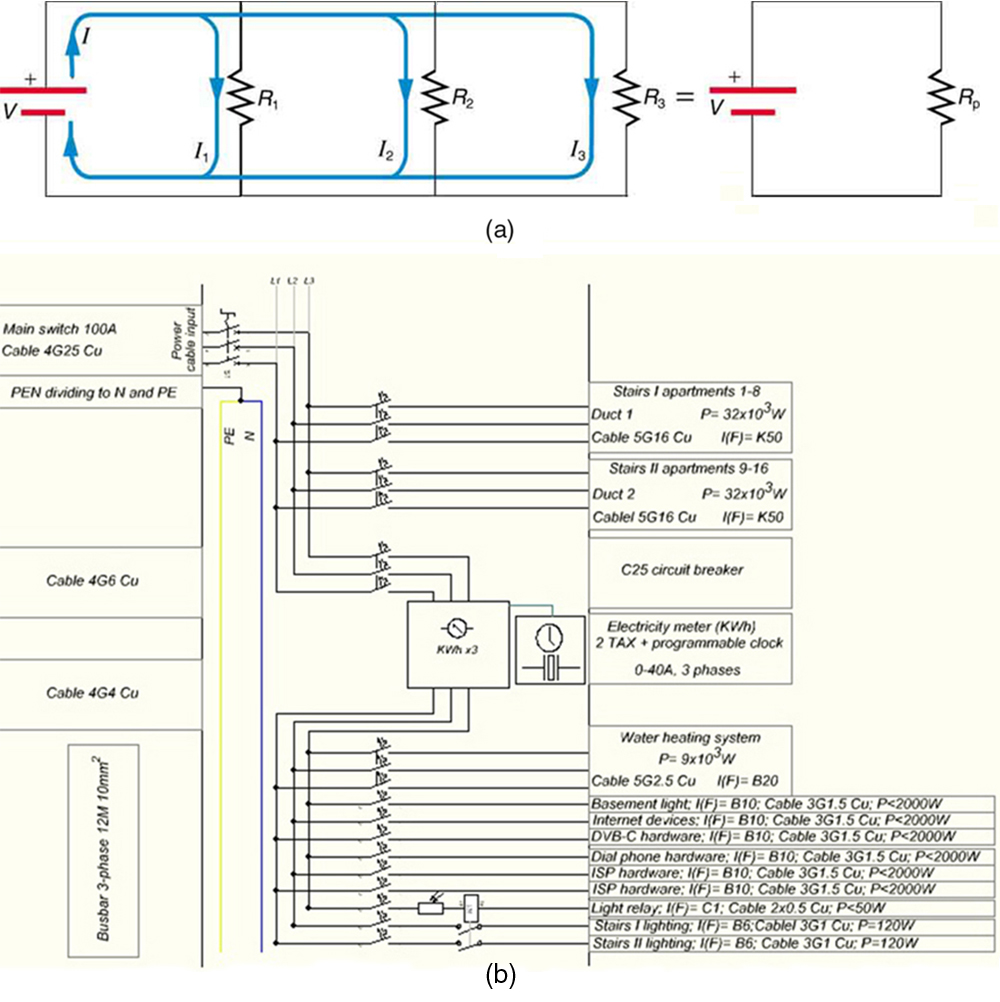

[link] shows resistors in parallel, wired to a voltage source. Resistors are in parallel when each resistor is connected directly to the voltage source by connecting wires having negligible resistance. Each resistor thus has the full voltage of the source applied to it.

Each resistor draws the same current it would if it alone were connected to the voltage source (provided the voltage source is not overloaded). For example, an automobile’s headlights, radio, and so on, are wired in parallel, so that they utilize the full voltage of the source and can operate completely independently. The same is true in your house, or any building. (See [link](b).)

To find an expression for the equivalent parallel resistance

, let us consider the currents that flow and how they are related to resistance. Since each resistor in the circuit has the full voltage, the currents flowing through the individual resistors are

,

, and

. Conservation of charge implies that the total current

produced by the source is the sum of these currents:

Substituting the expressions for the individual currents gives

Note that Ohm’s law for the equivalent single resistance gives

The terms inside the parentheses in the last two equations must be equal. Generalizing to any number of resistors, the total resistance

of a parallel connection is related to the individual resistances by

This relationship results in a total resistance

that is less than the smallest of the individual resistances. (This is seen in the next example.) When resistors are connected in parallel, more current flows from the source than would flow for any of them individually, and so the total resistance is lower.

Let the voltage output of the battery and resistances in the parallel connection in [link] be the same as the previously considered series connection:

,

,

, and

. (a) What is the total resistance? (b) Find the total current. (c) Calculate the currents in each resistor, and show these add to equal the total current output of the source. (d) Calculate the power dissipated by each resistor. (e) Find the power output of the source, and show that it equals the total power dissipated by the resistors.

Strategy and Solution for (a)

The total resistance for a parallel combination of resistors is found using the equation below. Entering known values gives

Thus,

(Note that in these calculations, each intermediate answer is shown with an extra digit.)

We must invert this to find the total resistance

. This yields

The total resistance with the correct number of significant digits is

Discussion for (a)

is, as predicted, less than the smallest individual resistance.

Strategy and Solution for (b)

The total current can be found from Ohm’s law, substituting

for the total resistance. This gives

Discussion for (b)

Current

for each device is much larger than for the same devices connected in series (see the previous example). A circuit with parallel connections has a smaller total resistance than the resistors connected in series.

Strategy and Solution for (c)

The individual currents are easily calculated from Ohm’s law, since each resistor gets the full voltage. Thus,

Similarly,

and

Discussion for (c)

The total current is the sum of the individual currents:

This is consistent with conservation of charge.

Strategy and Solution for (d)

The power dissipated by each resistor can be found using any of the equations relating power to current, voltage, and resistance, since all three are known. Let us use

, since each resistor gets full voltage. Thus,

Similarly,

and

Discussion for (d)

The power dissipated by each resistor is considerably higher in parallel than when connected in series to the same voltage source.

Strategy and Solution for (e)

The total power can also be calculated in several ways. Choosing

, and entering the total current, yields

Discussion for (e)

Total power dissipated by the resistors is also 179 W:

This is consistent with the law of conservation of energy.

Overall Discussion

Note that both the currents and powers in parallel connections are greater than for the same devices in series.

, and it is smaller than any individual resistance in the combination.

More complex connections of resistors are sometimes just combinations of series and parallel. These are commonly encountered, especially when wire resistance is considered. In that case, wire resistance is in series with other resistances that are in parallel.

Combinations of series and parallel can be reduced to a single equivalent resistance using the technique illustrated in [link]. Various parts are identified as either series or parallel, reduced to their equivalents, and further reduced until a single resistance is left. The process is more time consuming than difficult.

The simplest combination of series and parallel resistance, shown in [link], is also the most instructive, since it is found in many applications. For example,

could be the resistance of wires from a car battery to its electrical devices, which are in parallel.

and

could be the starter motor and a passenger compartment light. We have previously assumed that wire resistance is negligible, but, when it is not, it has important effects, as the next example indicates.

[link] shows the resistors from the previous two examples wired in a different way—a combination of series and parallel. We can consider

to be the resistance of wires leading to

and

. (a) Find the total resistance. (b) What is the

drop in

? (c) Find the current

through

. (d) What power is dissipated by

?

Strategy and Solution for (a)

To find the total resistance, we note that

and

are in parallel and their combination

is in series with

. Thus the total (equivalent) resistance of this combination is

First, we find

using the equation for resistors in parallel and entering known values:

Inverting gives

So the total resistance is

Discussion for (a)

The total resistance of this combination is intermediate between the pure series and pure parallel values (

and

, respectively) found for the same resistors in the two previous examples.

Strategy and Solution for (b)

To find the

drop in

, we note that the full current

flows through

. Thus its

drop is

We must find

before we can calculate

. The total current

is found using Ohm’s law for the circuit. That is,

Entering this into the expression above, we get

Discussion for (b)

The voltage applied to

and

is less than the total voltage by an amount

. When wire resistance is large, it can significantly affect the operation of the devices represented by

and

.

Strategy and Solution for (c)

To find the current through

, we must first find the voltage applied to it. We call this voltage

, because it is applied to a parallel combination of resistors. The voltage applied to both

and

is reduced by the amount

, and so it is

Now the current

through resistance

is found using Ohm’s law:

Discussion for (c)

The current is less than the 2.00 A that flowed through

when it was connected in parallel to the battery in the previous parallel circuit example.

Strategy and Solution for (d)

The power dissipated by

is given by

Discussion for (d)

The power is less than the 24.0 W this resistor dissipated when connected in parallel to the 12.0-V source.

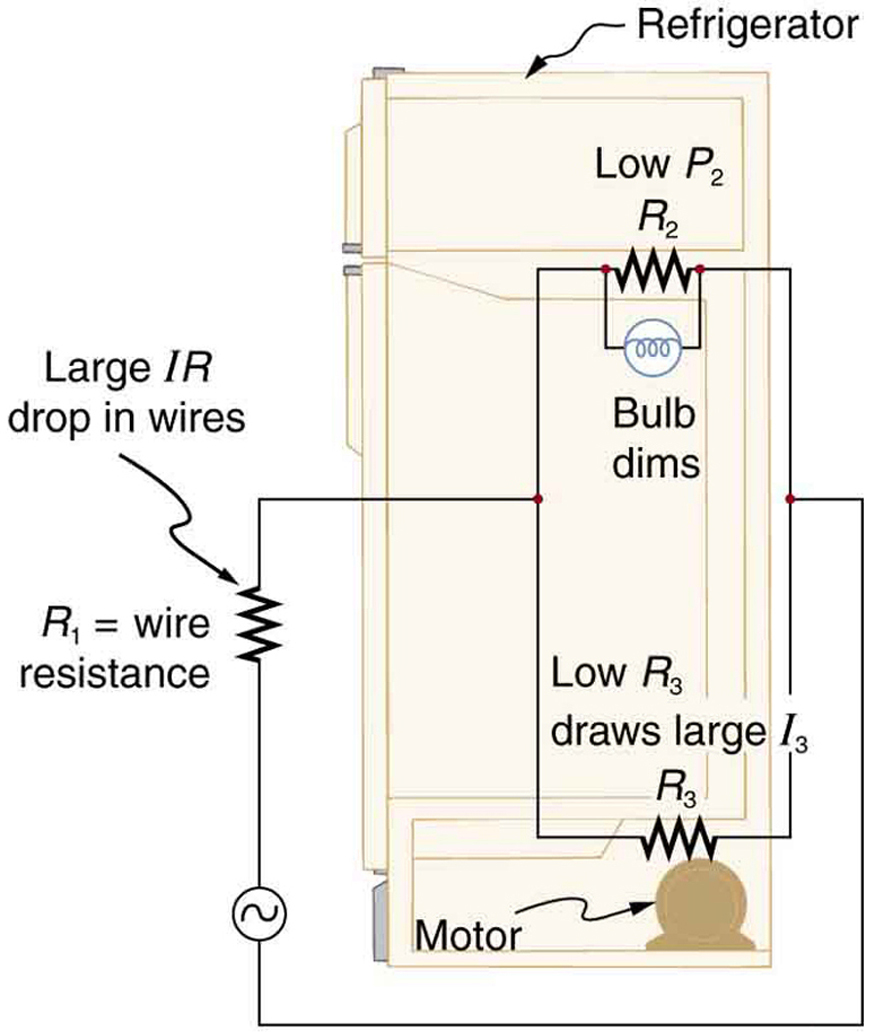

One implication of this last example is that resistance in wires reduces the current and power delivered to a resistor. If wire resistance is relatively large, as in a worn (or a very long) extension cord, then this loss can be significant. If a large current is drawn, the

drop in the wires can also be significant.

For example, when you are rummaging in the refrigerator and the motor comes on, the refrigerator light dims momentarily. Similarly, you can see the passenger compartment light dim when you start the engine of your car (although this may be due to resistance inside the battery itself).

What is happening in these high-current situations is illustrated in [link]. The device represented by

has a very low resistance, and so when it is switched on, a large current flows. This increased current causes a larger

drop in the wires represented by

, reducing the voltage across the light bulb (which is

), which then dims noticeably.

Can any arbitrary combination of resistors be broken down into series and parallel combinations? See if you can draw a circuit diagram of resistors that cannot be broken down into combinations of series and parallel.

No, there are many ways to connect resistors that are not combinations of series and parallel, including loops and junctions. In such cases Kirchhoff’s rules, to be introduced in Kirchhoff’s Rules, will allow you to analyze the circuit.

, the reciprocal must be taken with care.

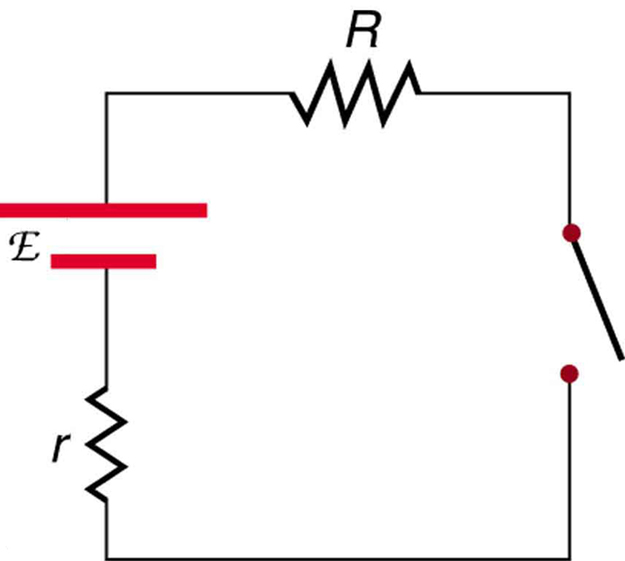

A switch has a variable resistance that is nearly zero when closed and extremely large when open, and it is placed in series with the device it controls. Explain the effect the switch in [link] has on current when open and when closed.

What is the voltage across the open switch in [link]?

There is a voltage across an open switch, such as in [link]. Why, then, is the power dissipated by the open switch small?

Why is the power dissipated by a closed switch, such as in [link], small?

A student in a physics lab mistakenly wired a light bulb, battery, and switch as shown in [link]. Explain why the bulb is on when the switch is open, and off when the switch is closed. (Do not try this—it is hard on the battery!)

Knowing that the severity of a shock depends on the magnitude of the current through your body, would you prefer to be in series or parallel with a resistance, such as the heating element of a toaster, if shocked by it? Explain.

Would your headlights dim when you start your car’s engine if the wires in your automobile were superconductors? (Do not neglect the battery’s internal resistance.) Explain.

Some strings of holiday lights are wired in series to save wiring costs. An old version utilized bulbs that break the electrical connection, like an open switch, when they burn out. If one such bulb burns out, what happens to the others? If such a string operates on 120 V and has 40 identical bulbs, what is the normal operating voltage of each? Newer versions use bulbs that short circuit, like a closed switch, when they burn out. If one such bulb burns out, what happens to the others? If such a string operates on 120 V and has 39 remaining identical bulbs, what is then the operating voltage of each?

If two household lightbulbs rated 60 W and 100 W are connected in series to household power, which will be brighter? Explain.

Suppose you are doing a physics lab that asks you to put a resistor into a circuit, but all the resistors supplied have a larger resistance than the requested value. How would you connect the available resistances to attempt to get the smaller value asked for?

Before World War II, some radios got power through a “resistance cord” that had a significant resistance. Such a resistance cord reduces the voltage to a desired level for the radio’s tubes and the like, and it saves the expense of a transformer. Explain why resistance cords become warm and waste energy when the radio is on.

Some light bulbs have three power settings (not including zero), obtained from multiple filaments that are individually switched and wired in parallel. What is the minimum number of filaments needed for three power settings?

Note: Data taken from figures can be assumed to be accurate to three significant digits.

(a) What is the resistance of ten

resistors connected in series? (b) In parallel?

(a)

(b)

(a) What is the resistance of a

, a

, and a

resistor connected in series? (b) In parallel?

What are the largest and smallest resistances you can obtain by connecting a

, a

, and a

resistor together?

(a)

(b)

An 1800-W toaster, a 1400-W electric frying pan, and a 75-W lamp are plugged into the same outlet in a 15-A, 120-V circuit. (The three devices are in parallel when plugged into the same socket.). (a) What current is drawn by each device? (b) Will this combination blow the 15-A fuse?

Your car’s 30.0-W headlight and 2.40-kW starter are ordinarily connected in parallel in a 12.0-V system. What power would one headlight and the starter consume if connected in series to a 12.0-V battery? (Neglect any other resistance in the circuit and any change in resistance in the two devices.)

(a) Given a 48.0-V battery and

and

resistors, find the current and power for each when connected in series. (b) Repeat when the resistances are in parallel.

Referring to the example combining series and parallel circuits and [link], calculate

in the following two different ways: (a) from the known values of

and

; (b) using Ohm’s law for

. In both parts explicitly show how you follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategies for Series and Parallel Resistors.

(a) 0.74 A

(b) 0.742 A

Referring to [link]: (a) Calculate

and note how it compares with

found in the first two example problems in this module. (b) Find the total power supplied by the source and compare it with the sum of the powers dissipated by the resistors.

Refer to [link] and the discussion of lights dimming when a heavy appliance comes on. (a) Given the voltage source is 120 V, the wire resistance is

, and the bulb is nominally 75.0 W, what power will the bulb dissipate if a total of 15.0 A passes through the wires when the motor comes on? Assume negligible change in bulb resistance. (b) What power is consumed by the motor?

(a) 60.8 W

(b) 3.18 kW

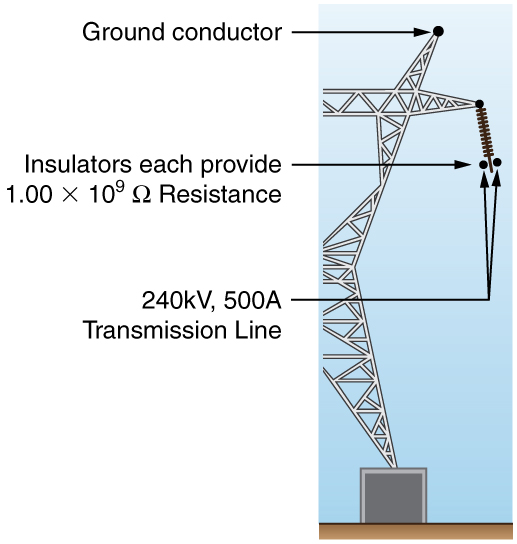

A 240-kV power transmission line carrying

is hung from grounded metal towers by ceramic insulators, each having a

resistance. [link]. (a) What is the resistance to ground of 100 of these insulators? (b) Calculate the power dissipated by 100 of them. (c) What fraction of the power carried by the line is this? Explicitly show how you follow the steps in the Problem-Solving Strategies for Series and Parallel Resistors.

Show that if two resistors

and

are combined and one is much greater than the other (

): (a) Their series resistance is very nearly equal to the greater resistance

. (b) Their parallel resistance is very nearly equal to smaller resistance

.

(a)

(b)

,

so that

Unreasonable Results

Two resistors, one having a resistance of

, are connected in parallel to produce a total resistance of

. (a) What is the value of the second resistance? (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

Unreasonable Results

Two resistors, one having a resistance of

, are connected in series to produce a total resistance of

. (a) What is the value of the second resistance? (b) What is unreasonable about this result? (c) Which assumptions are unreasonable or inconsistent?

(a)

(b) Resistance cannot be negative.

(c) Series resistance is said to be less than one of the resistors, but it must be greater than any of the resistors.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/031da8d3-b525-429c-80cf-6c8ed997733a@11.1

Attribution: