After a morning of playing outside, four-year-old Carli ran inside for lunch. After taking a bite of her fried egg, she pushed it away and whined, “It’s too slimy, Mommy. I don’t want any more.” But her mother, in no mood for games, curtly replied that if she wanted to go back outside she had better finish her lunch. Reluctantly, Carli complied, trying hard not to gag as she choked down the runny egg.

That night, Carli woke up feeling nauseated. She cried for her parents and then began to vomit. Her parents tried to comfort her, but she continued to vomit all night and began to have diarrhea and run a fever. By the morning, her parents were very worried. They rushed her to the emergency room.

Jump to the next Clinical Focus box.

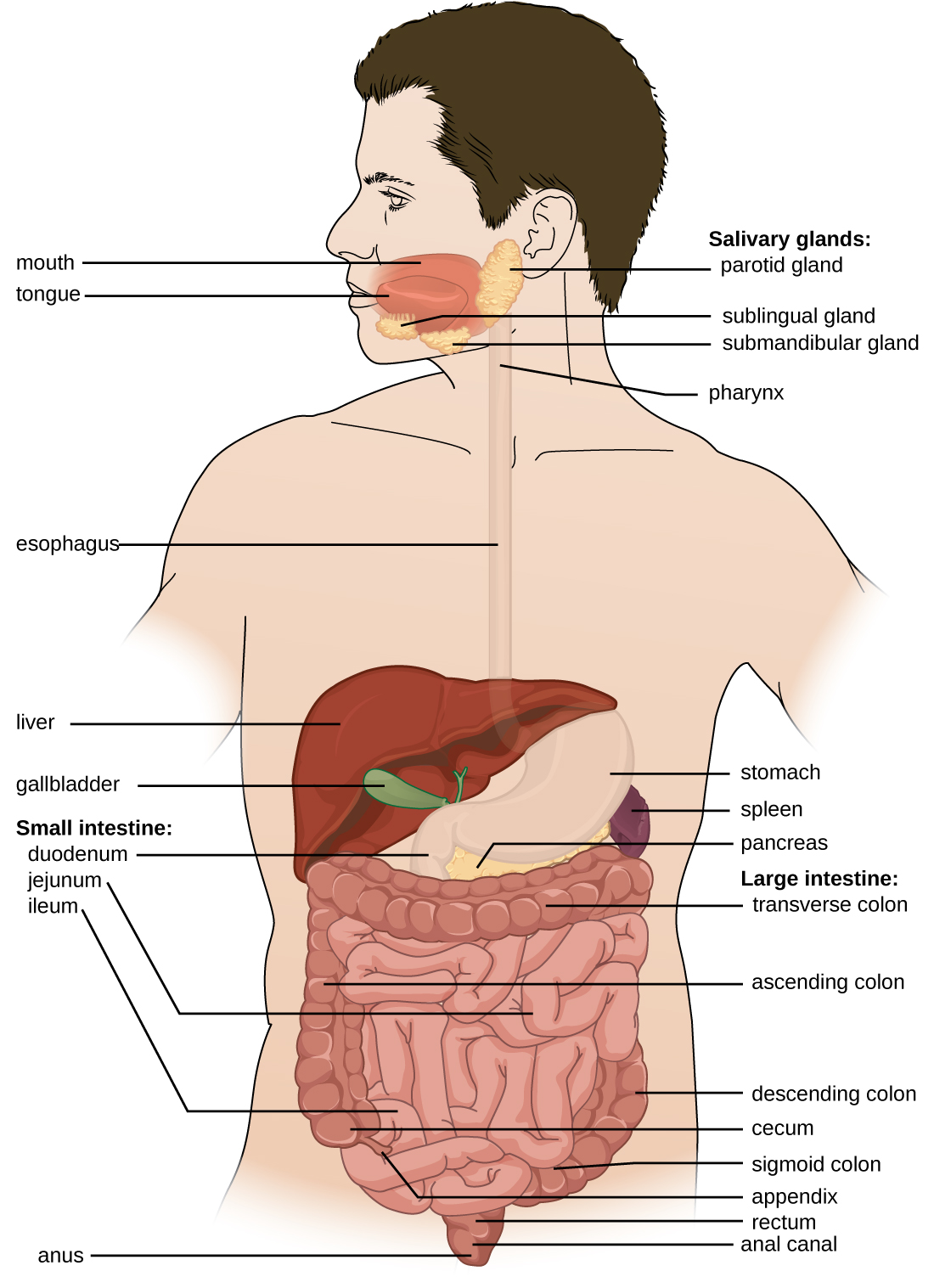

The human digestive system, or the gastrointestinal (GI) tract, begins with the mouth and ends with the anus. The parts of the mouth include the teeth, the gums, the tongue, the oral vestibule (the space between the gums, lips, and teeth), and the oral cavity proper (the space behind the teeth and gums). Other parts of the GI tract are the pharynx, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, large intestine, rectum, and anus ([link]). Accessory digestive organs include the salivary glands, liver, gallbladder, spleen, and pancreas.

The digestive system contains normal microbiota, including archaea, bacteria, fungi, protists, and even viruses. Because this microbiota is important for normal functioning of the digestive system, alterations to the microbiota by antibiotics or diet can be harmful. Additionally, the introduction of pathogens to the GI tract can cause infections and diseases. In this section, we will review the microbiota found in a healthy digestive tract and the general signs and symptoms associated with oral and GI infections.

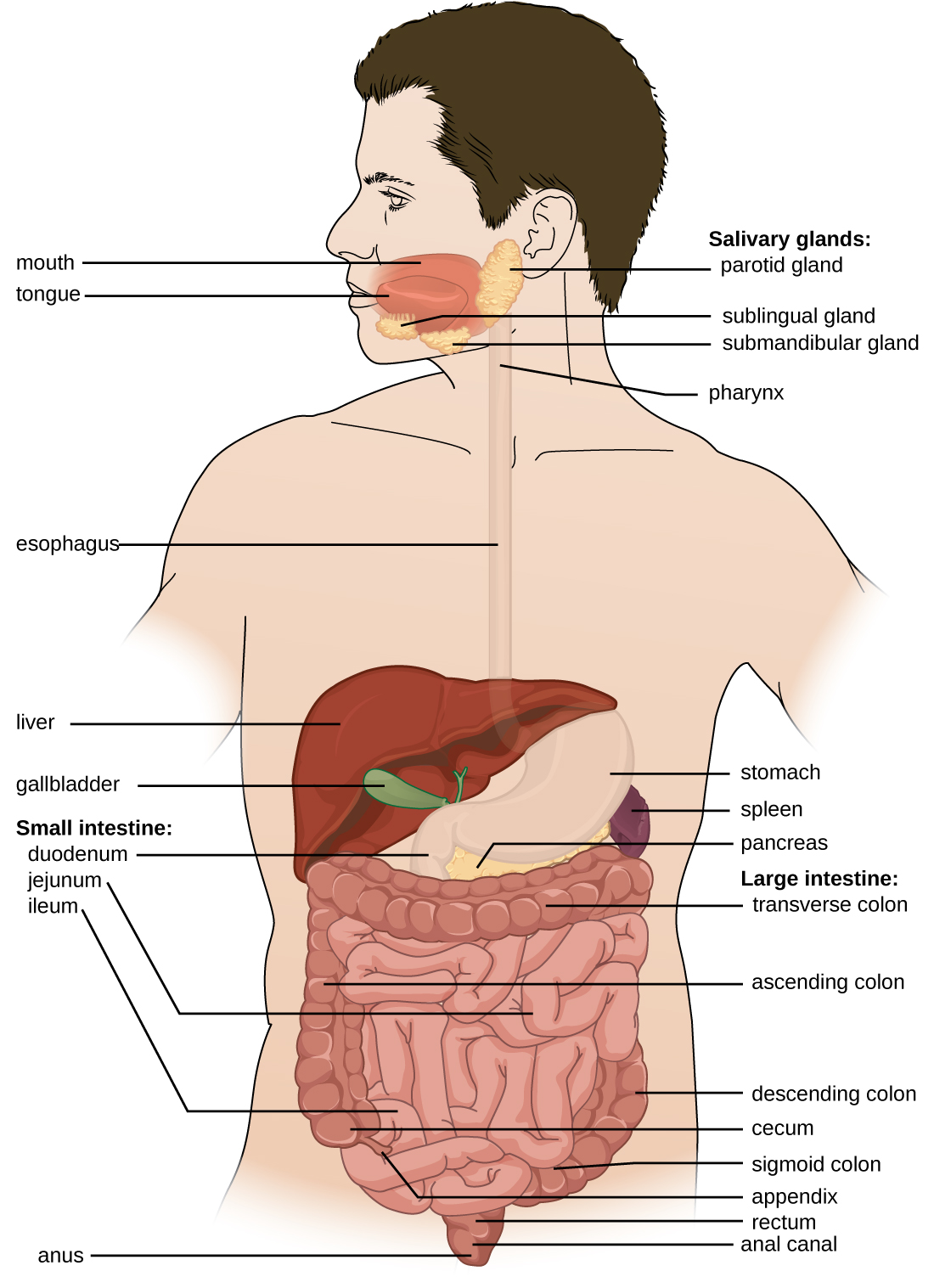

Food enters the digestive tract through the mouth, where mechanical digestion (by chewing) and chemical digestion (by enzymes in saliva) begin. Within the mouth are the tongue, teeth, and salivary glands, including the parotid, sublingual, and submandibular glands ([link]). The salivary glands produce saliva, which lubricates food and contains digestive enzymes.

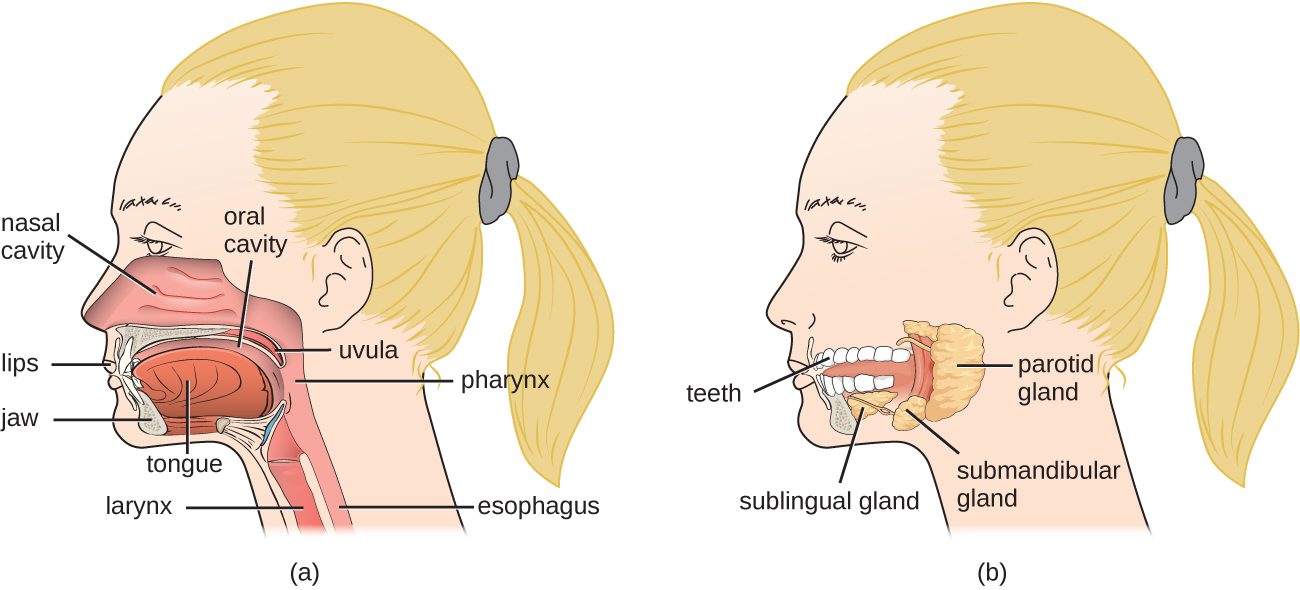

The structure of a tooth ([link]) begins with the visible outer surface, called the crown, which has to be extremely hard to withstand the force of biting and chewing. The crown is covered with enamel, which is the hardest material in the body. Underneath the crown, a layer of relatively hard dentin extends into the root of the tooth around the innermost pulp cavity, which includes the pulp chamber at the top of the tooth and pulp canal, or root canal, located in the root. The pulp that fills the pulp cavity is rich in blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, connective tissue, and nerves. The root of the tooth and some of the crown are covered with cementum, which works with the periodontal ligament to anchor the tooth in place in the jaw bone. The soft tissues surrounding the teeth and bones are called gums, or gingiva. The gingival space or gingival crevice is located between the gums and teeth.

Microbes such as bacteria and archaea are abundant in the mouth and coat all of the surfaces of the oral cavity. However, different structures, such as the teeth or cheeks, host unique communities of both aerobic and anaerobic microbes. Some factors appear to work against making the mouth hospitable to certain microbes. For example, chewing allows microbes to mix better with saliva so they can be swallowed or spit out more easily. Saliva also contains enzymes, including lysozyme, which can damage microbial cells. Recall that lysozyme is part of the first line of defense in the innate immune system and cleaves the β-(1,4) glycosidic linkages between N-acetylglucosamine (NAG) and N-acetylmuramic acid (NAM) in bacterial peptidoglycan (see Chemical Defenses). Additionally, fluids containing immunoglobulins and phagocytic cells are produced in the gingival spaces. Despite all of these chemical and mechanical activities, the mouth supports a large microbial community.

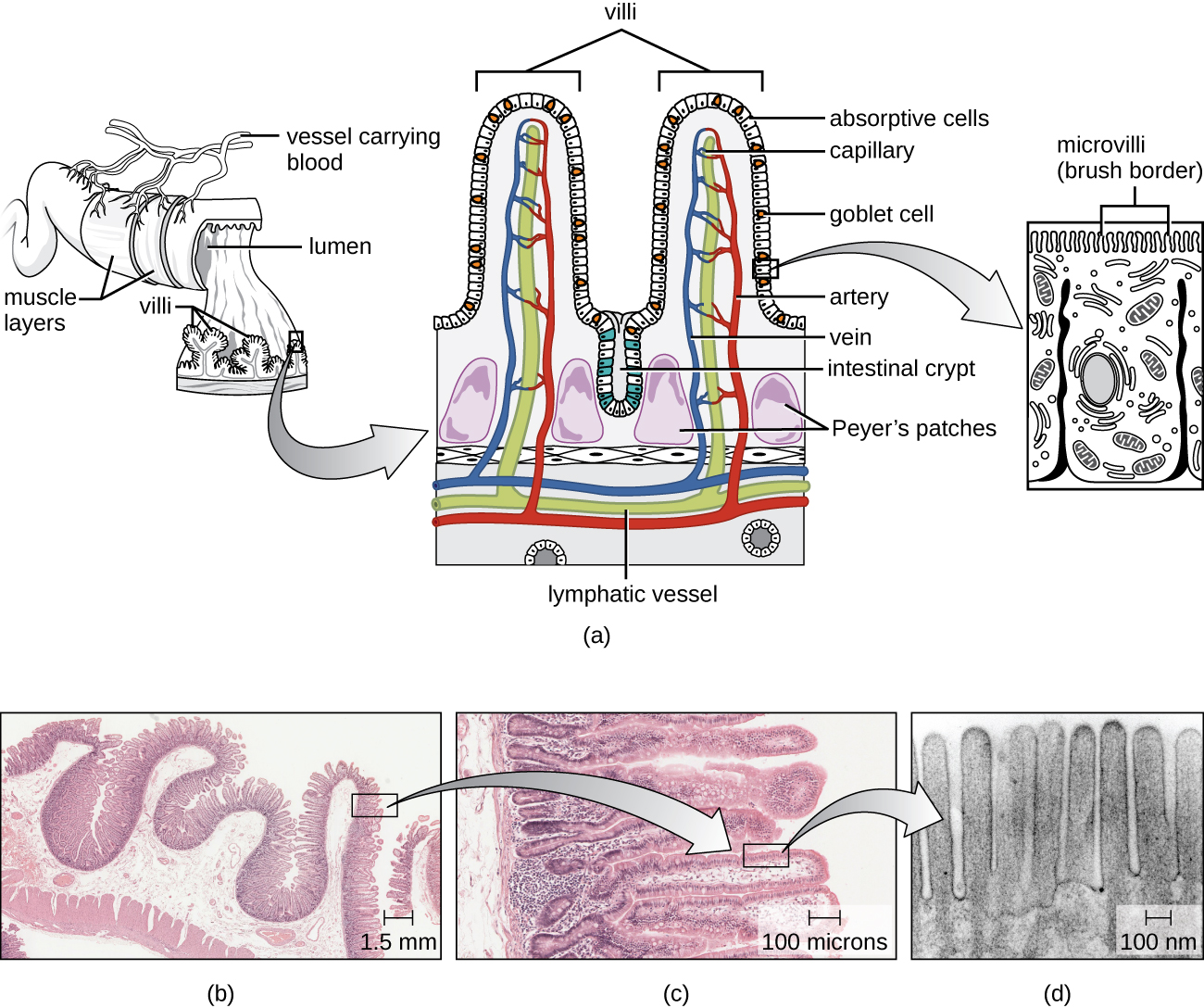

As food leaves the oral cavity, it travels through the pharynx, or the back of the throat, and moves into the esophagus, which carries the food from the pharynx to the stomach without adding any additional digestive enzymes. The stomach produces mucus to protect its lining, as well as digestive enzymes and acid to break down food. Partially digested food then leaves the stomach through the pyloric sphincter, reaching the first part of the small intestine called the duodenum. Pancreatic juice, which includes enzymes and bicarbonate ions, is released into the small intestine to neutralize the acidic material from the stomach and to assist in digestion. Bile, produced by the liver but stored in the gallbladder, is also released into the small intestine to emulsify fats so that they can travel in the watery environment of the small intestine. Digestion continues in the small intestine, where the majority of nutrients contained in the food are absorbed. Simple columnar epithelial cells called enterocytes line the lumen surface of the small intestinal folds called villi. Each enterocyte has smaller microvilli (cytoplasmic membrane extensions) on the cellular apical surface that increase the surface area to allow more absorption of nutrients to occur ([link]).

Digested food leaves the small intestine and moves into the large intestine, or colon, where there is a more diverse microbiota. Near this junction, there is a small pouch in the large intestine called the cecum, which attaches to the appendix. Further digestion occurs throughout the colon and water is reabsorbed, then waste is excreted through the rectum, the last section of the colon, and out of the body through the anus ([link]).

The environment of most of the GI tract is harsh, which serves two purposes: digestion and immunity. The stomach is an extremely acidic environment (pH 1.5–3.5) due to the gastric juices that break down food and kill many ingested microbes; this helps prevent infection from pathogens. The environment in the small intestine is less harsh and is able to support microbial communities. Microorganisms present in the small intestine can include lactobacilli, diptherioids and the fungus Candida. On the other hand, the large intestine (colon) contains a diverse and abundant microbiota that is important for normal function. These microbes include Bacteriodetes (especially the genera Bacteroides and Prevotella) and Firmicutes (especially members of the genus Clostridium). Methanogenic archaea and some fungi are also present, among many other species of bacteria. These microbes all aid in digestion and contribute to the production of feces, the waste excreted from the digestive tract, and flatus, the gas produced from microbial fermentation of undigested food. They can also produce valuable nutrients. For example, lactic acid bacteria such as bifidobacteria can synthesize vitamins, such as vitamin B12, folate, and riboflavin, that humans cannot synthesize themselves. E. coli found in the intestine can also break down food and help the body produce vitamin K, which is important for blood coagulation.

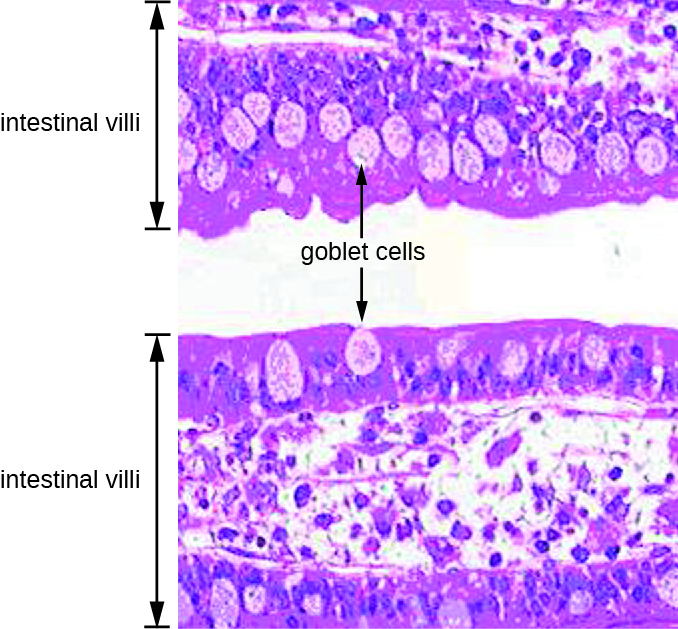

The GI tract has several other methods of reducing the risk of infection by pathogens. Small aggregates of underlying lymphoid tissue in the ileum, called Peyer’s patches ([link]), detect pathogens in the intestines via microfold (M) cells, which transfer antigens from the lumen of the intestine to the lymphocytes on Peyer’s patches to induce an immune response. The Peyer’s patches then secrete IgA and other pathogen-specific antibodies into the intestinal lumen to help keep intestinal microbes at safe levels. Goblet cells, which are modified simple columnar epithelial cells, also line the GI tract ([link]). Goblet cells secrete a gel-forming mucin, which is the major component of mucus. The production of a protective layer of mucus helps reduce the risk of pathogens reaching deeper tissues.

The constant movement of materials through the gastrointestinal tract also helps to move transient pathogens out of the body. In fact, feces are composed of approximately 25% microbes, 25% sloughed epithelial cells, 25% mucus, and 25% digested or undigested food. Finally, the normal microbiota provides an additional barrier to infection via a variety of mechanisms. For example, these organisms outcompete potential pathogens for space and nutrients within the intestine. This is known as competitive exclusion. Members of the microbiota may also secrete protein toxins known as bacteriocins that are able to bind to specific receptors on the surface of susceptible bacteria.

Despite numerous defense mechanisms that protect against infection, all parts of the digestive tract can become sites of infection or intoxication. The term food poisoning is sometimes used as a catch-all for GI infections and intoxications, but not all forms of GI disease originate with foodborne pathogens or toxins.

In the mouth, fermentation by anaerobic microbes produces acids that damage the teeth and gums. This can lead to tooth decay, cavities, and periodontal disease, a condition characterized by chronic inflammation and erosion of the gums. Additionally, some pathogens can cause infections of the mucosa, glands, and other structures in the mouth, resulting in inflammation, sores, cankers, and other lesions. An open sore in the mouth or GI tract is typically called an ulcer.

Infections and intoxications of the lower GI tract often produce symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, aches, and fever. In some cases, vomiting and diarrhea may cause severe dehydration and other complications that can become serious or fatal. Various clinical terms are used to describe gastrointestinal symptoms. For example, gastritis is an inflammation of the stomach lining that results in swelling and enteritis refers to inflammation of the intestinal mucosa. When the inflammation involves both the stomach lining and the intestinal lining, the condition is called gastroenteritis. Inflammation of the liver is called hepatitis. Inflammation of the colon, called colitis, commonly occurs in cases of food intoxication. Because an inflamed colon does not reabsorb water as effectively as it normally does, stools become watery, causing diarrhea. Damage to the epithelial cells of the colon can also cause bleeding and excess mucus to appear in watery stools, a condition called dysentery.

Which of the following is NOT a way the normal microbiota of the intestine helps to prevent infection?

D

What types of microbes live in the intestines?

A

The part of the gastrointestinal tract with the largest natural microbiota is the _________.

Large intestine or colon

How does the diarrhea caused by dysentery differ from other types of diarrhea?

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/e42bd376-624b-4c0f-972f-e0c57998e765@5.3

Attribution: