Many types of genetic engineering have yielded clear benefits with few apparent risks. Few would question, for example, the value of our now abundant supply of human insulin produced by genetically engineered bacteria. However, many emerging applications of genetic engineering are much more controversial, often because their potential benefits are pitted against significant risks, real or perceived. This is certainly the case for gene therapy, a clinical application of genetic engineering that may one day provide a cure for many diseases but is still largely an experimental approach to treatment.

Human diseases that result from genetic mutations are often difficult to treat with drugs or other traditional forms of therapy because the signs and symptoms of disease result from abnormalities in a patient’s genome. For example, a patient may have a genetic mutation that prevents the expression of a specific protein required for the normal function of a particular cell type. This is the case in patients with Severe Combined Immunodeficiency (SCID), a genetic disease that impairs the function of certain white blood cells essential to the immune system.

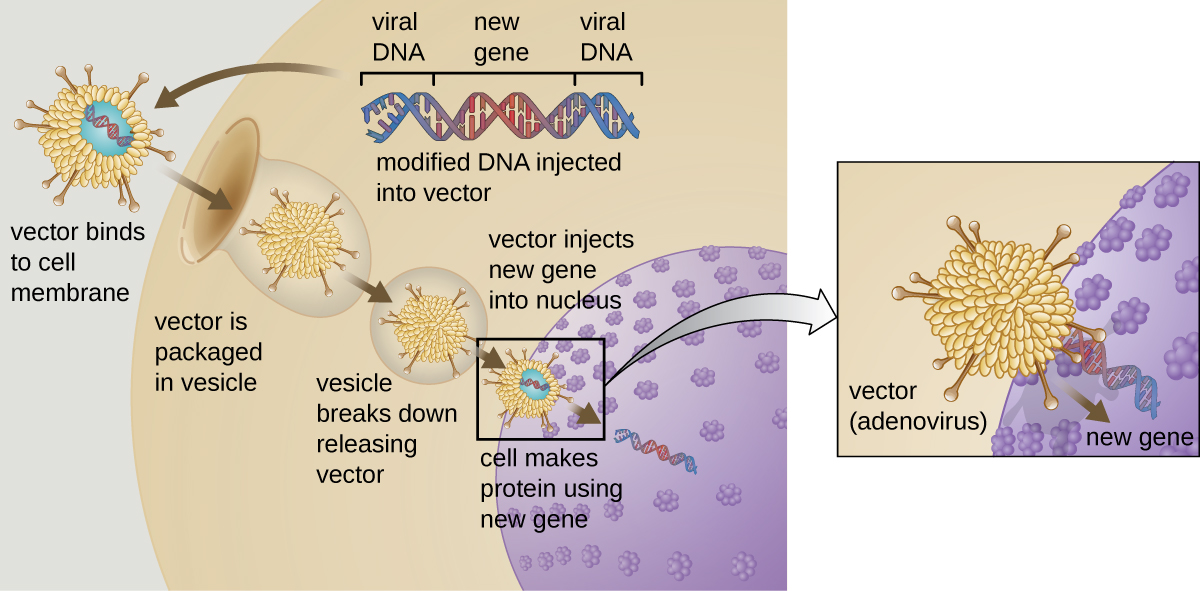

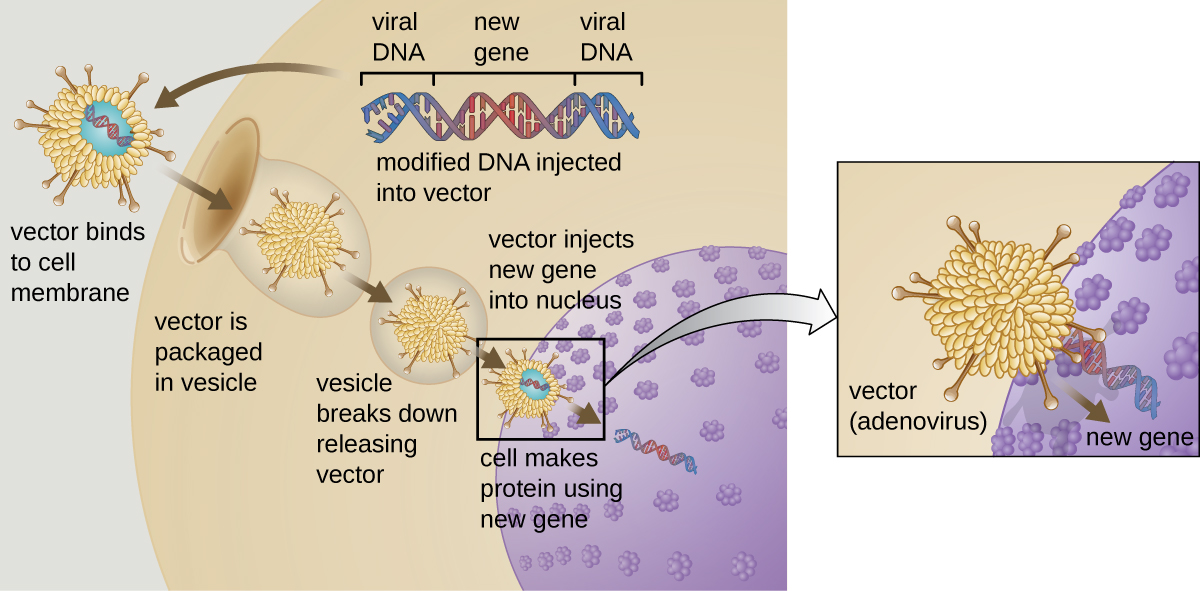

Gene therapy attempts to correct genetic abnormalities by introducing a nonmutated, functional gene into the patient’s genome. The nonmutated gene encodes a functional protein that the patient would otherwise be unable to produce. Viral vectors such as adenovirus are sometimes used to introduce the functional gene; part of the viral genome is removed and replaced with the desired gene ([link]). More advanced forms of gene therapy attempt to correct the mutation at the original site in the genome, such as is the case with treatment of SCID.

So far, gene therapies have proven relatively ineffective, with the possible exceptions of treatments for cystic fibrosis and adenosine deaminase deficiency, a type of SCID. Other trials have shown the clear hazards of attempting genetic manipulation in complex multicellular organisms like humans. In some patients, the use of an adenovirus vector can trigger an unanticipated inflammatory response from the immune system, which may lead to organ failure. Moreover, because viruses can often target multiple cell types, the virus vector may infect cells not targeted for the therapy, damaging these other cells and possibly leading to illnesses such as cancer. Another potential risk is that the modified virus could revert to being infectious and cause disease in the patient. Lastly, there is a risk that the inserted gene could unintentionally inactivate another important gene in the patient’s genome, disrupting normal cell cycling and possibly leading to tumor formation and cancer. Because gene therapy involves so many risks, candidates for gene therapy need to be fully informed of these risks before providing informed consent to undergo the therapy.

The risks of gene therapy were realized in the 1999 case of Jesse Gelsinger, an 18-year-old patient who received gene therapy as part of a clinical trial at the University of Pennsylvania. Jesse received gene therapy for a condition called ornithine transcarbamylase (OTC) deficiency, which leads to ammonia accumulation in the blood due to deficient ammonia processing. Four days after the treatment, Jesse died after a massive immune response to the adenovirus vector.1

Until that point, researchers had not really considered an immune response to the vector to be a legitimate risk, but on investigation, it appears that the researchers had some evidence suggesting that this was a possible outcome. Prior to Jesse’s treatment, several other human patients had suffered side effects of the treatment, and three monkeys used in a trial had died as a result of inflammation and clotting disorders. Despite this information, it appears that neither Jesse nor his family were made aware of these outcomes when they consented to the therapy. Jesse’s death was the first patient death due to a gene therapy treatment and resulted in the immediate halting of the clinical trial in which he was involved, the subsequent halting of all other gene therapy trials at the University of Pennsylvania, and the investigation of all other gene therapy trials in the United States. As a result, the regulation and oversight of gene therapy overall was reexamined, resulting in new regulatory protocols that are still in place today.

Presently, there is significant oversight of gene therapy clinical trials. At the federal level, three agencies regulate gene therapy in parallel: the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), the Office of Human Research Protection (OHRP), and the Recombinant DNA Advisory Committee (RAC) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). Along with several local agencies, these federal agencies interact with the institutional review board to ensure that protocols are in place to protect patient safety during clinical trials. Compliance with these protocols is enforced mostly on the local level in cooperation with the federal agencies. Gene therapies are currently under the most extensive federal and local review compared to other types of therapies, which are more typically only under the review of the FDA. Some researchers believe that these extensive regulations actually inhibit progress in gene therapy research. In 2013, the Institute of Medicine (now the National Academy of Medicine) called upon the NIH to relax its review of gene therapy trials in most cases.2 However, ensuring patient safety continues to be of utmost concern.

Beyond the health risks of gene therapy, the ability to genetically modify humans poses a number of ethical issues related to the limits of such “therapy.” While current research is focused on gene therapy for genetic diseases, scientists might one day apply these methods to manipulate other genetic traits not perceived as desirable. This raises questions such as:

The ability to alter reproductive cells using gene therapy could also generate new ethical dilemmas. To date, the various types of gene therapies have been targeted to somatic cells, the non-reproductive cells within the body. Because somatic cell traits are not inherited, any genetic changes accomplished by somatic-cell gene therapy would not be passed on to offspring. However, should scientists successfully introduce new genes to germ cells (eggs or sperm), the resulting traits could be passed on to offspring. This approach, called germ-line gene therapy, could potentially be used to combat heritable diseases, but it could also lead to unintended consequences for future generations. Moreover, there is the question of informed consent, because those impacted by germ-line gene therapy are unborn and therefore unable to choose whether they receive the therapy. For these reasons, the U.S. government does not currently fund research projects investigating germ-line gene therapies in humans.

While there are currently no gene therapies on the market in the United States, many are in the pipeline and it is likely that some will eventually be approved. With recent advances in gene therapies targeting p53, a gene whose somatic cell mutations have been implicated in over 50% of human cancers,3 cancer treatments through gene therapies could become much more widespread once they reach the commercial market.

Bringing any new therapy to market poses ethical questions that pit the expected benefits against the risks. How quickly should new therapies be brought to the market? How can we ensure that new therapies have been sufficiently tested for safety and effectiveness before they are marketed to the public? The process by which new therapies are developed and approved complicates such questions, as those involved in the approval process are often under significant pressure to get a new therapy approved even in the face of significant risks.

To receive FDA approval for a new therapy, researchers must collect significant laboratory data from animal trials and submit an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER). Following a 30-day waiting period during which the FDA reviews the IND, clinical trials involving human subjects may begin. If the FDA perceives a problem prior to or during the clinical trial, the FDA can order a “clinical hold” until any problems are addressed. During clinical trials, researchers collect and analyze data on the therapy’s effectiveness and safety, including any side effects observed. Once the therapy meets FDA standards for effectiveness and safety, the developers can submit a New Drug Application (NDA) that details how the therapy will be manufactured, packaged, monitored, and administered.

Because new gene therapies are frequently the result of many years (even decades) of laboratory and clinical research, they require a significant financial investment. By the time a therapy has reached the clinical trials stage, the financial stakes are high for pharmaceutical companies and their shareholders. This creates potential conflicts of interest that can sometimes affect the objective judgment of researchers, their funders, and even trial participants. The Jesse Gelsinger case (see Case in Point: Gene Therapy Gone Wrong) is a classic example. Faced with a life-threatening disease and no reasonable treatments available, it is easy to see why a patient might be eager to participate in a clinical trial no matter the risks. It is also easy to see how a researcher might view the short-term risks for a small group of study participants as a small price to pay for the potential benefits of a game-changing new treatment.

Gelsinger’s death led to increased scrutiny of gene therapy, and subsequent negative outcomes of gene therapy have resulted in the temporary halting of clinical trials pending further investigation. For example, when children in France treated with gene therapy for SCID began to develop leukemia several years after treatment, the FDA temporarily stopped clinical trials of similar types of gene therapy occurring in the United States.4 Cases like these highlight the need for researchers and health professionals not only to value human well-being and patients’ rights over profitability, but also to maintain scientific objectivity when evaluating the risks and benefits of new therapies.

At what point can the FDA halt the development or use of gene therapy?

D

_____________ is a common viral vector used in gene therapy for introducing a new gene into a specifically targeted cell type.

Adenovirus

Briefly describe the risks associated with somatic cell gene therapy.

Compare the ethical issues involved in the use of somatic cell gene therapy and germ-line gene therapy.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/e42bd376-624b-4c0f-972f-e0c57998e765@5.3

Attribution: