Watson and Crick’s identification of the structure of DNA in 1953 was the seminal event in the field of genetic engineering. Since the 1970s, there has been a veritable explosion in scientists’ ability to manipulate DNA in ways that have revolutionized the fields of biology, medicine, diagnostics, forensics, and industrial manufacturing. Many of the molecular tools discovered in recent decades have been produced using prokaryotic microbes. In this chapter, we will explore some of those tools, especially as they relate to applications in medicine and health care.

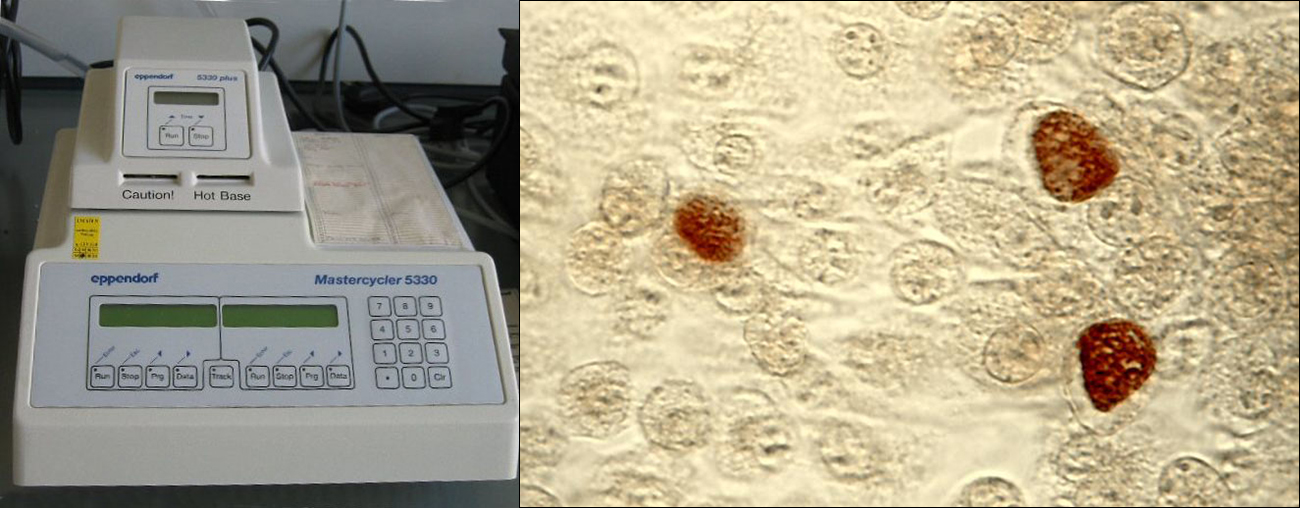

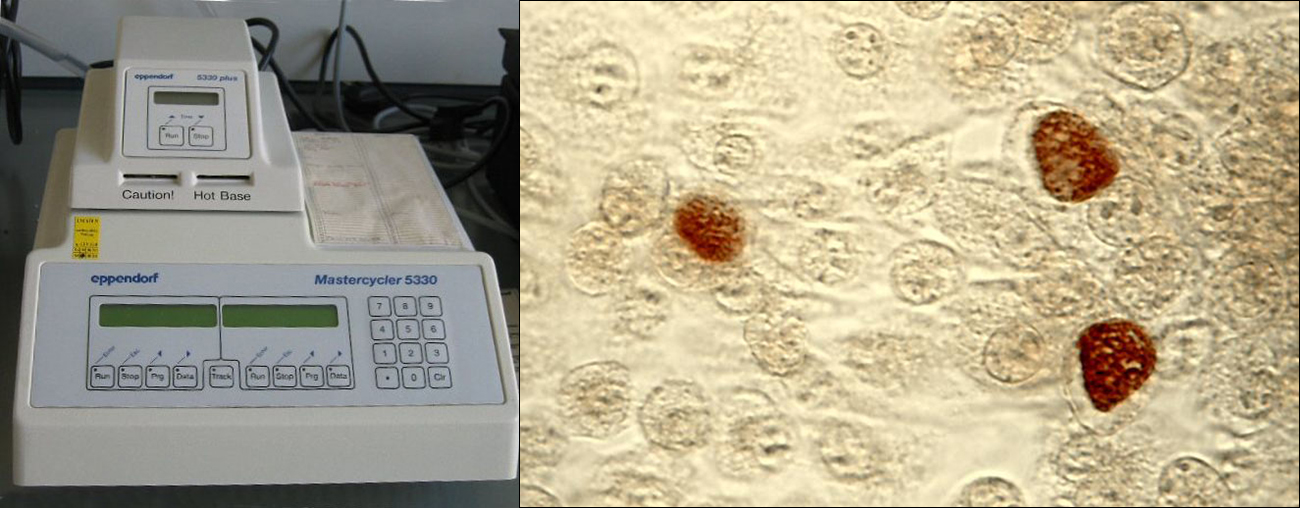

As an example, the thermal cycler in [link] is used to perform a diagnostic technique called the polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which relies on DNA polymerase enzymes from thermophilic bacteria. Other molecular tools, such as restriction enzymes and plasmids obtained from microorganisms, allow scientists to insert genes from humans or other organisms into microorganisms. The microorganisms are then grown on an industrial scale to synthesize products such as insulin, vaccines, and biodegradable polymers. These are just a few of the numerous applications of microbial genetics that we will explore in this chapter.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/e42bd376-624b-4c0f-972f-e0c57998e765@5.3

Attribution: