A mutation is a heritable change in the DNA sequence of an organism. The resulting organism, called a mutant, may have a recognizable change in phenotype compared to the wild type, which is the phenotype most commonly observed in nature. A change in the DNA sequence is conferred to mRNA through transcription, and may lead to an altered amino acid sequence in a protein on translation. Because proteins carry out the vast majority of cellular functions, a change in amino acid sequence in a protein may lead to an altered phenotype for the cell and organism.

There are several types of mutations that are classified according to how the DNA molecule is altered. One type, called a point mutation, affects a single base and most commonly occurs when one base is substituted or replaced by another. Mutations also result from the addition of one or more bases, known as an insertion, or the removal of one or more bases, known as a deletion.

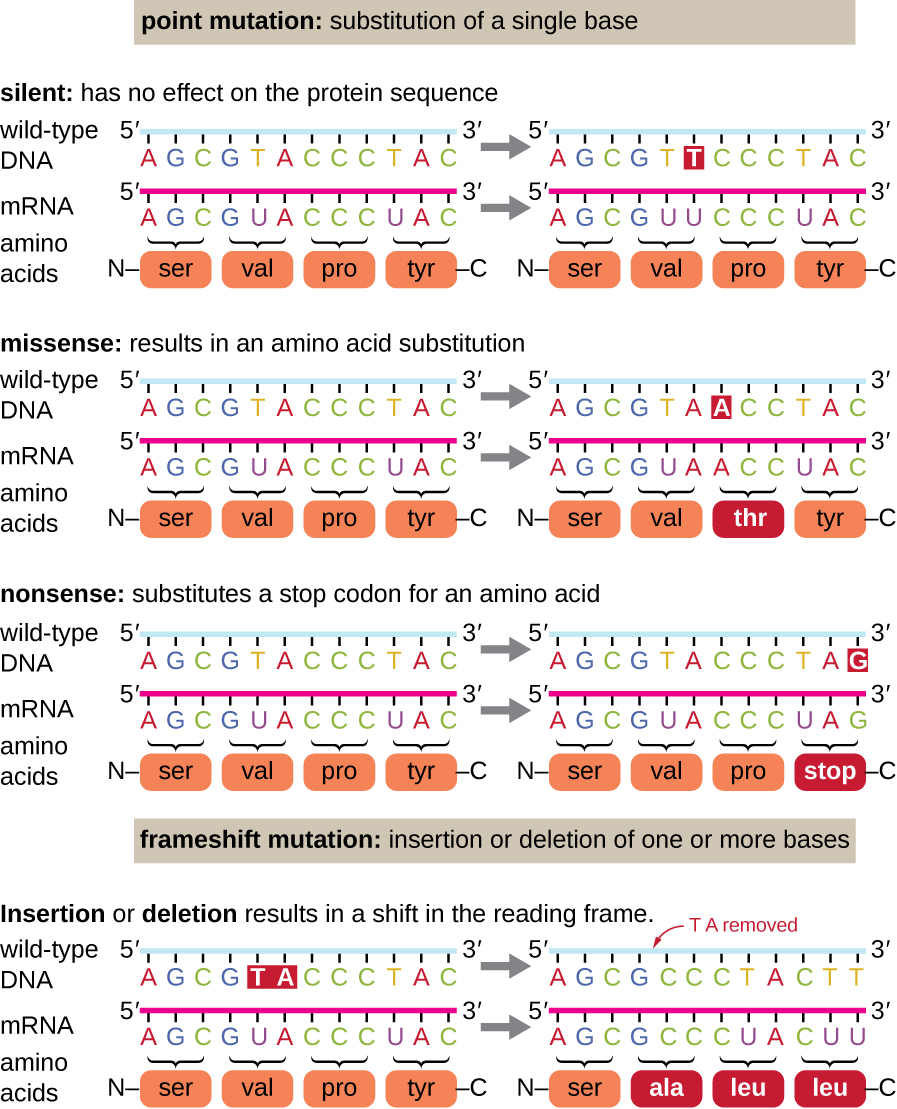

Point mutations may have a wide range of effects on protein function ([link]). As a consequence of the degeneracy of the genetic code, a point mutation will commonly result in the same amino acid being incorporated into the resulting polypeptide despite the sequence change. This change would have no effect on the protein’s structure, and is thus called a silent mutation. A missense mutation results in a different amino acid being incorporated into the resulting polypeptide. The effect of a missense mutation depends on how chemically different the new amino acid is from the wild-type amino acid. The location of the changed amino acid within the protein also is important. For example, if the changed amino acid is part of the enzyme’s active site, then the effect of the missense mutation may be significant. Many missense mutations result in proteins that are still functional, at least to some degree. Sometimes the effects of missense mutations may be only apparent under certain environmental conditions; such missense mutations are called conditional mutations. Rarely, a missense mutation may be beneficial. Under the right environmental conditions, this type of mutation may give the organism that harbors it a selective advantage. Yet another type of point mutation, called a nonsense mutation, converts a codon encoding an amino acid (a sense codon) into a stop codon (a nonsense codon). Nonsense mutations result in the synthesis of proteins that are shorter than the wild type and typically not functional.

Deletions and insertions also cause various effects. Because codons are triplets of nucleotides, insertions or deletions in groups of three nucleotides may lead to the insertion or deletion of one or more amino acids and may not cause significant effects on the resulting protein’s functionality. However, frameshift mutations, caused by insertions or deletions of a number of nucleotides that are not a multiple of three are extremely problematic because a shift in the reading frame results ([link]). Because ribosomes read the mRNA in triplet codons, frameshift mutations can change every amino acid after the point of the mutation. The new reading frame may also include a stop codon before the end of the coding sequence. Consequently, proteins made from genes containing frameshift mutations are nearly always nonfunctional.

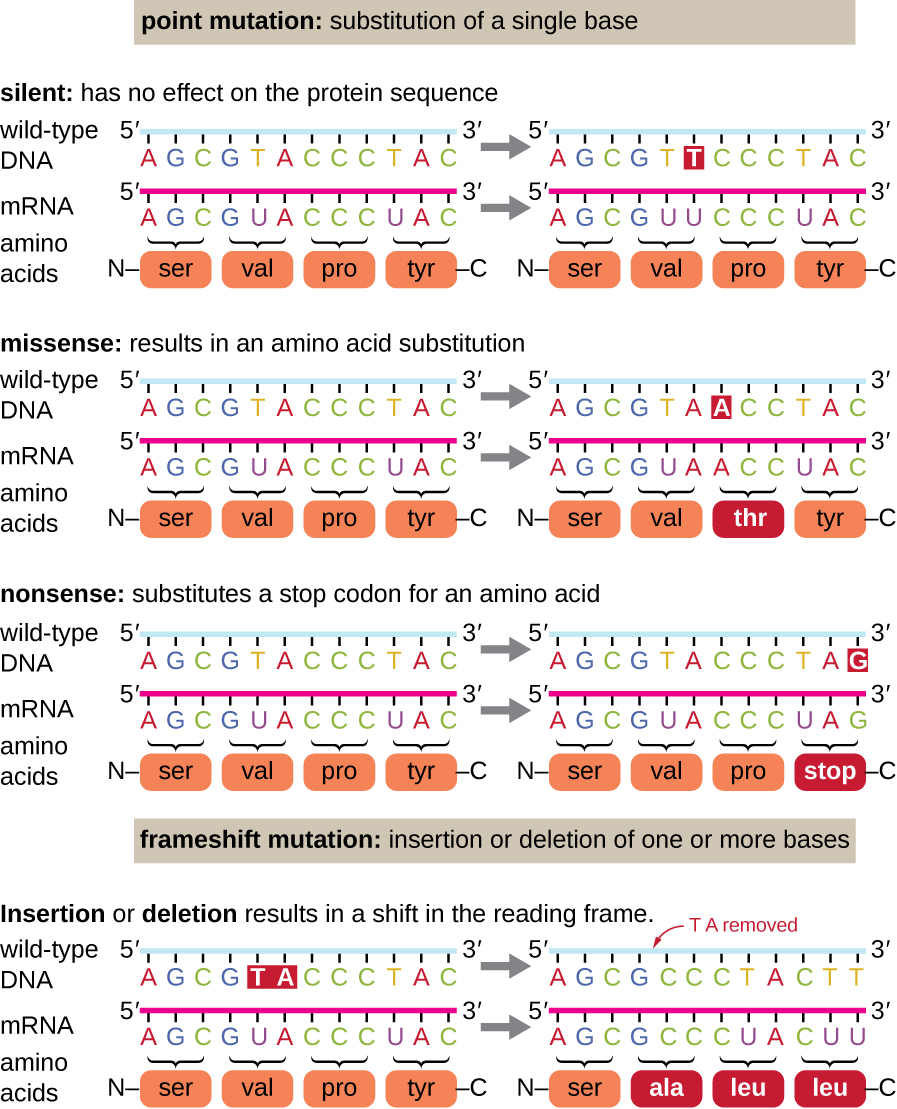

Since the first case of infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) was reported in 1981, nearly 40 million people have died from HIV infection,1 the virus that causes acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). The virus targets helper T cells that play a key role in bridging the innate and adaptive immune response, infecting and killing cells normally involved in the body’s response to infection. There is no cure for HIV infection, but many drugs have been developed to slow or block the progression of the virus. Although individuals around the world may be infected, the highest prevalence among people 15–49 years old is in sub-Saharan Africa, where nearly one person in 20 is infected, accounting for greater than 70% of the infections worldwide2 ([link]). Unfortunately, this is also a part of the world where prevention strategies and drugs to treat the infection are the most lacking.

In recent years, scientific interest has been piqued by the discovery of a few individuals from northern Europe who are resistant to HIV infection. In 1998, American geneticist Stephen J. O’Brien at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and colleagues published the results of their genetic analysis of more than 4,000 individuals. These indicated that many individuals of Eurasian descent (up to 14% in some ethnic groups) have a deletion mutation, called CCR5-delta 32, in the gene encoding CCR5. CCR5 is a coreceptor found on the surface of T cells that is necessary for many strains of the virus to enter the host cell. The mutation leads to the production of a receptor to which HIV cannot effectively bind and thus blocks viral entry. People homozygous for this mutation have greatly reduced susceptibility to HIV infection, and those who are heterozygous have some protection from infection as well.

It is not clear why people of northern European descent, specifically, carry this mutation, but its prevalence seems to be highest in northern Europe and steadily decreases in populations as one moves south. Research indicates that the mutation has been present since before HIV appeared and may have been selected for in European populations as a result of exposure to the plague or smallpox. This mutation may protect individuals from plague (caused by the bacterium Yersinia pestis) and smallpox (caused by the variola virus) because this receptor may also be involved in these diseases. The age of this mutation is a matter of debate, but estimates suggest it appeared between 1875 years to 225 years ago, and may have been spread from Northern Europe through Viking invasions.

This exciting finding has led to new avenues in HIV research, including looking for drugs to block CCR5 binding to HIV in individuals who lack the mutation. Although DNA testing to determine which individuals carry the CCR5-delta 32 mutation is possible, there are documented cases of individuals homozygous for the mutation contracting HIV. For this reason, DNA testing for the mutation is not widely recommended by public health officials so as not to encourage risky behavior in those who carry the mutation. Nevertheless, inhibiting the binding of HIV to CCR5 continues to be a valid strategy for the development of drug therapies for those infected with HIV.

Mistakes in the process of DNA replication can cause spontaneous mutations to occur. The error rate of DNA polymerase is one incorrect base per billion base pairs replicated. Exposure to mutagens can cause induced mutations, which are various types of chemical agents or radiation ([link]). Exposure to a mutagen can increase the rate of mutation more than 1000-fold. Mutagens are often also carcinogens, agents that cause cancer. However, whereas nearly all carcinogens are mutagenic, not all mutagens are necessarily carcinogens.

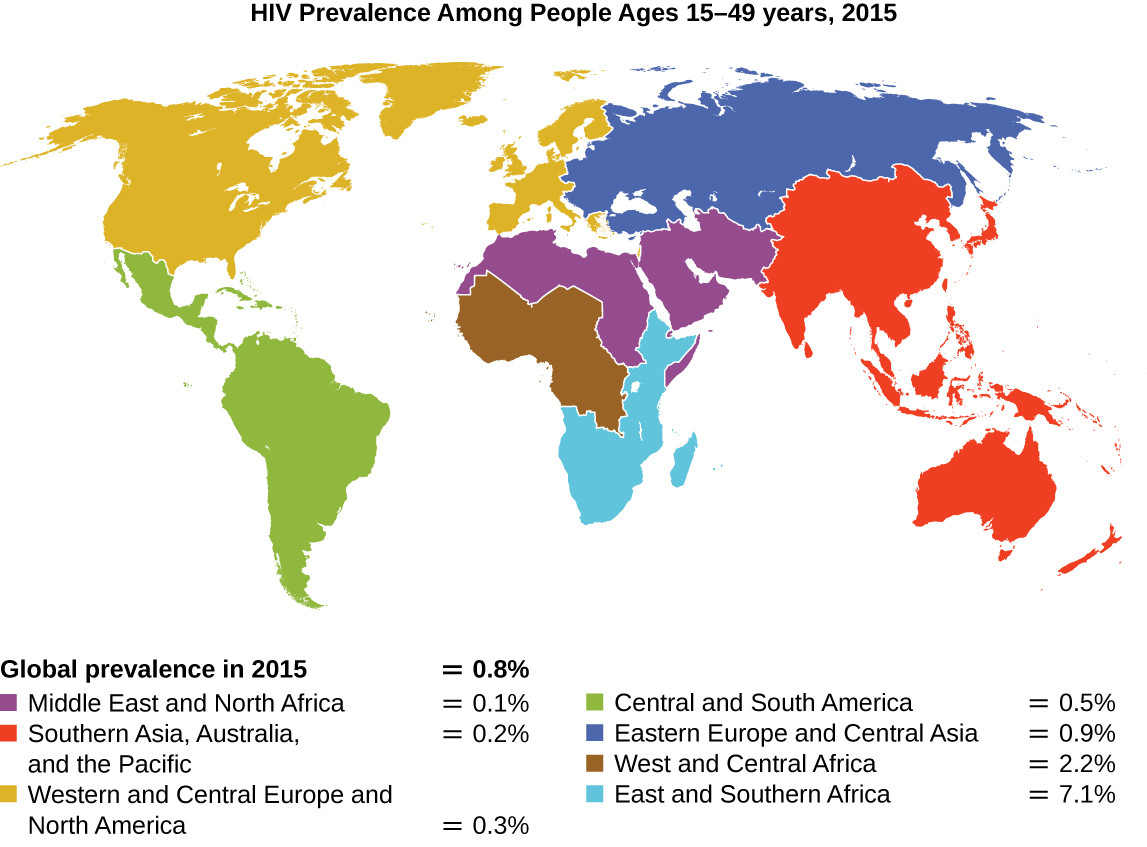

Various types of chemical mutagens interact directly with DNA either by acting as nucleoside analogs or by modifying nucleotide bases. Chemicals called nucleoside analogs are structurally similar to normal nucleotide bases and can be incorporated into DNA during replication ([link]). These base analogs induce mutations because they often have different base-pairing rules than the bases they replace. Other chemical mutagens can modify normal DNA bases, resulting in different base-pairing rules. For example, nitrous acid deaminates cytosine, converting it to uracil. Uracil then pairs with adenine in a subsequent round of replication, resulting in the conversion of a GC base pair to an AT base pair. Nitrous acid also deaminates adenine to hypoxanthine, which base pairs with cytosine instead of thymine, resulting in the conversion of a TA base pair to a CG base pair.

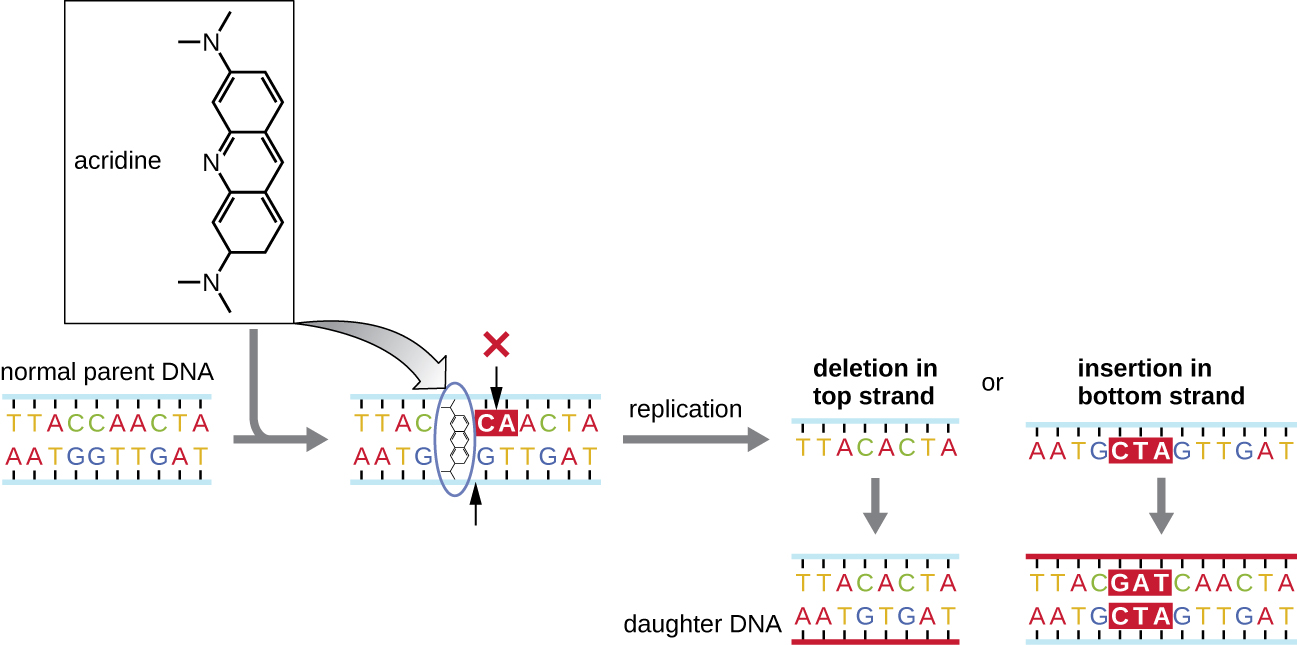

Chemical mutagens known as intercalating agents work differently. These molecules slide between the stacked nitrogenous bases of the DNA double helix, distorting the molecule and creating atypical spacing between nucleotide base pairs ([link]). As a result, during DNA replication, DNA polymerase may either skip replicating several nucleotides (creating a deletion) or insert extra nucleotides (creating an insertion). Either outcome may lead to a frameshift mutation. Combustion products like polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons are particularly dangerous intercalating agents that can lead to mutation-caused cancers. The intercalating agents ethidium bromide and acridine orange are commonly used in the laboratory to stain DNA for visualization and are potential mutagens.

Exposure to either ionizing or nonionizing radiation can each induce mutations in DNA, although by different mechanisms. Strong ionizing radiation like X-rays and gamma rays can cause single- and double-stranded breaks in the DNA backbone through the formation of hydroxyl radicals on radiation exposure ([link]). Ionizing radiation can also modify bases; for example, the deamination of cytosine to uracil, analogous to the action of nitrous acid.3 Ionizing radiation exposure is used to kill microbes to sterilize medical devices and foods, because of its dramatic nonspecific effect in damaging DNA, proteins, and other cellular components (see Using Physical Methods to Control Microorganisms).

Nonionizing radiation, like ultraviolet light, is not energetic enough to initiate these types of chemical changes. However, nonionizing radiation can induce dimer formation between two adjacent pyrimidine bases, commonly two thymines, within a nucleotide strand. During thymine dimer formation, the two adjacent thymines become covalently linked and, if left unrepaired, both DNA replication and transcription are stalled at this point. DNA polymerase may proceed and replicate the dimer incorrectly, potentially leading to frameshift or point mutations.

| A Summary of Mutagenic Agents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Mutagenic Agents | Mode of Action | Effect on DNA | Resulting Type of Mutation |

| Nucleoside analogs | |||

| 2-aminopurine | Is inserted in place of A but base pairs with C | Converts AT to GC base pair | Point |

| 5-bromouracil | Is inserted in place of T but base pairs with G | Converts AT to GC base pair | Point |

| Nucleotide-modifying agent | |||

| Nitrous oxide | Deaminates C to U | Converts GC to AT base pair | Point |

| Intercalating agents | |||

| Acridine orange, ethidium bromide, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons | Distorts double helix, creates unusual spacing between nucleotides | Introduces small deletions and insertions | Frameshift |

| Ionizing radiation | |||

| X-rays, γ-rays | Forms hydroxyl radicals | Causes single- and double-strand DNA breaks | Repair mechanisms may introduce mutations |

| X-rays, γ-rays | Modifies bases (e.g., deaminating C to U) | Converts GC to AT base pair | Point |

| Nonionizing radiation | |||

| Ultraviolet | Forms pyrimidine (usually thymine) dimers | Causes DNA replication errors | Frameshift or point |

The process of DNA replication is highly accurate, but mistakes can occur spontaneously or be induced by mutagens. Uncorrected mistakes can lead to serious consequences for the phenotype. Cells have developed several repair mechanisms to minimize the number of mutations that persist.

Most of the mistakes introduced during DNA replication are promptly corrected by most DNA polymerases through a function called proofreading. In proofreading, the DNA polymerase reads the newly added base, ensuring that it is complementary to the corresponding base in the template strand before adding the next one. If an incorrect base has been added, the enzyme makes a cut to release the wrong nucleotide and a new base is added.

Some errors introduced during replication are corrected shortly after the replication machinery has moved. This mechanism is called mismatch repair. The enzymes involved in this mechanism recognize the incorrectly added nucleotide, excise it, and replace it with the correct base. One example is the methyl-directed mismatch repair in E. coli. The DNA is hemimethylated. This means that the parental strand is methylated while the newly synthesized daughter strand is not. It takes several minutes before the new strand is methylated. Proteins MutS, MutL, and MutH bind to the hemimethylated site where the incorrect nucleotide is found. MutH cuts the nonmethylated strand (the new strand). An exonuclease removes a portion of the strand (including the incorrect nucleotide). The gap formed is then filled in by DNA pol III and ligase.

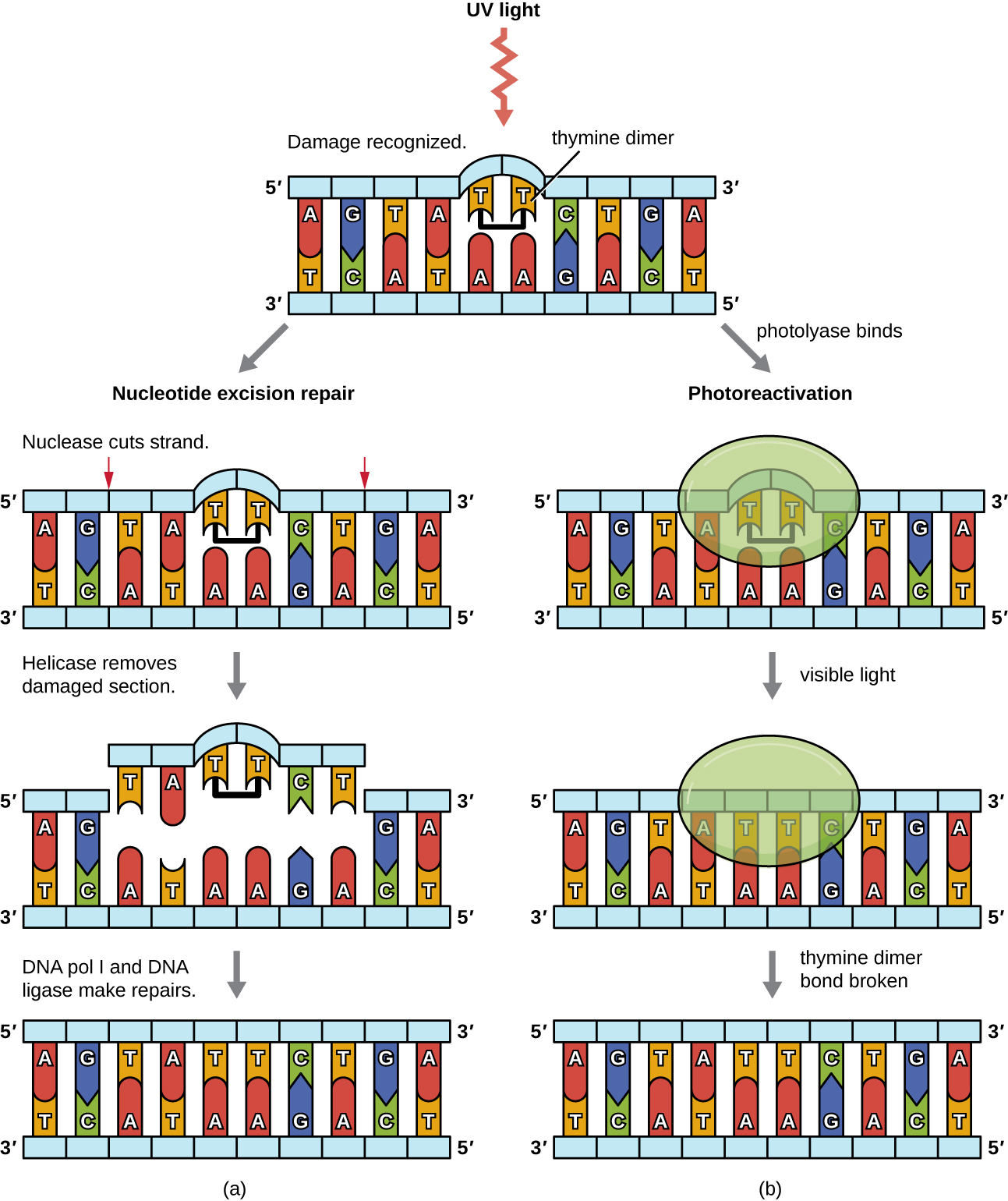

Because the production of thymine dimers is common (many organisms cannot avoid ultraviolet light), mechanisms have evolved to repair these lesions. In nucleotide excision repair (also called dark repair), enzymes remove the pyrimidine dimer and replace it with the correct nucleotides ([link]). In E. coli, the DNA is scanned by an enzyme complex. If a distortion in the double helix is found that was introduced by the pyrimidine dimer, the enzyme complex cuts the sugar-phosphate backbone several bases upstream and downstream of the dimer, and the segment of DNA between these two cuts is then enzymatically removed. DNA pol I replaces the missing nucleotides with the correct ones and DNA ligase seals the gap in the sugar-phosphate backbone.

The direct repair (also called light repair) of thymine dimers occurs through the process of photoreactivation in the presence of visible light. An enzyme called photolyase recognizes the distortion in the DNA helix caused by the thymine dimer and binds to the dimer. Then, in the presence of visible light, the photolyase enzyme changes conformation and breaks apart the thymine dimer, allowing the thymines to again correctly base pair with the adenines on the complementary strand. Photoreactivation appears to be present in all organisms, with the exception of placental mammals, including humans. Photoreactivation is particularly important for organisms chronically exposed to ultraviolet radiation, like plants, photosynthetic bacteria, algae, and corals, to prevent the accumulation of mutations caused by thymine dimer formation.

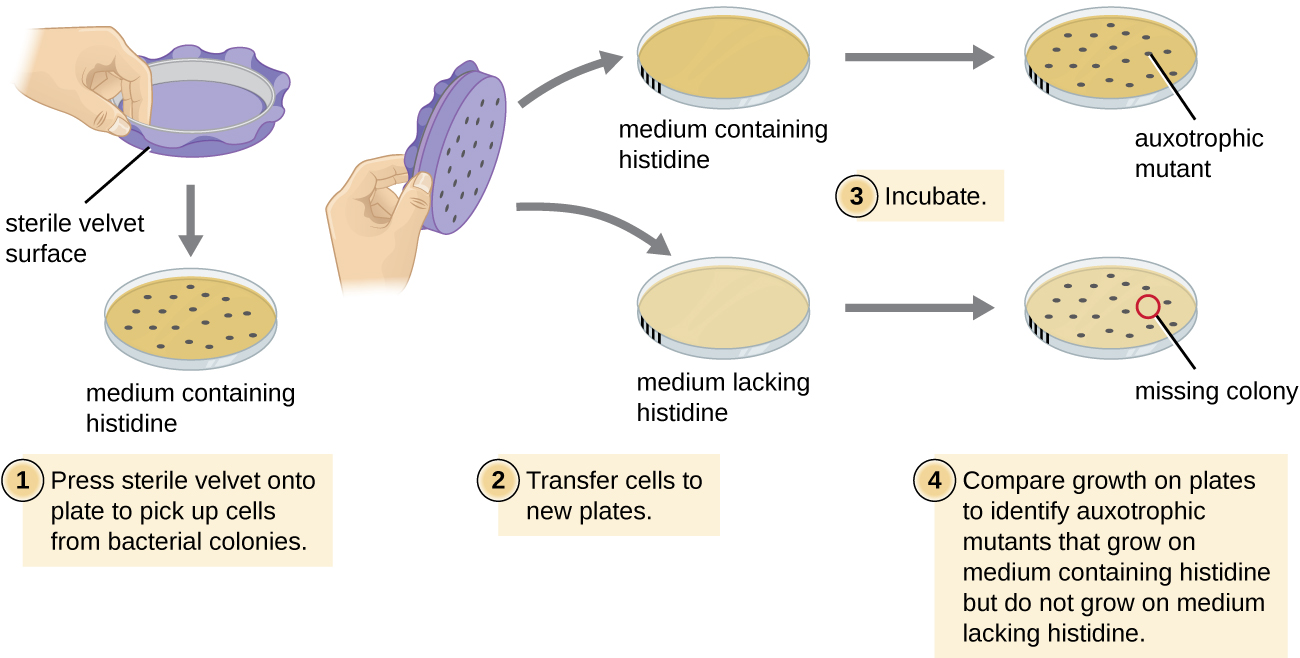

One common technique used to identify bacterial mutants is called replica plating. This technique is used to detect nutritional mutants, called auxotrophs, which have a mutation in a gene encoding an enzyme in the biosynthesis pathway of a specific nutrient, such as an amino acid. As a result, whereas wild-type cells retain the ability to grow normally on a medium lacking the specific nutrient, auxotrophs are unable to grow on such a medium. During replica plating ([link]), a population of bacterial cells is mutagenized and then plated as individual cells on a complex nutritionally complete plate and allowed to grow into colonies. Cells from these colonies are removed from this master plate, often using sterile velvet. This velvet, containing cells, is then pressed in the same orientation onto plates of various media. At least one plate should also be nutritionally complete to ensure that cells are being properly transferred between the plates. The other plates lack specific nutrients, allowing the researcher to discover various auxotrophic mutants unable to produce specific nutrients. Cells from the corresponding colony on the nutritionally complete plate can be used to recover the mutant for further study.

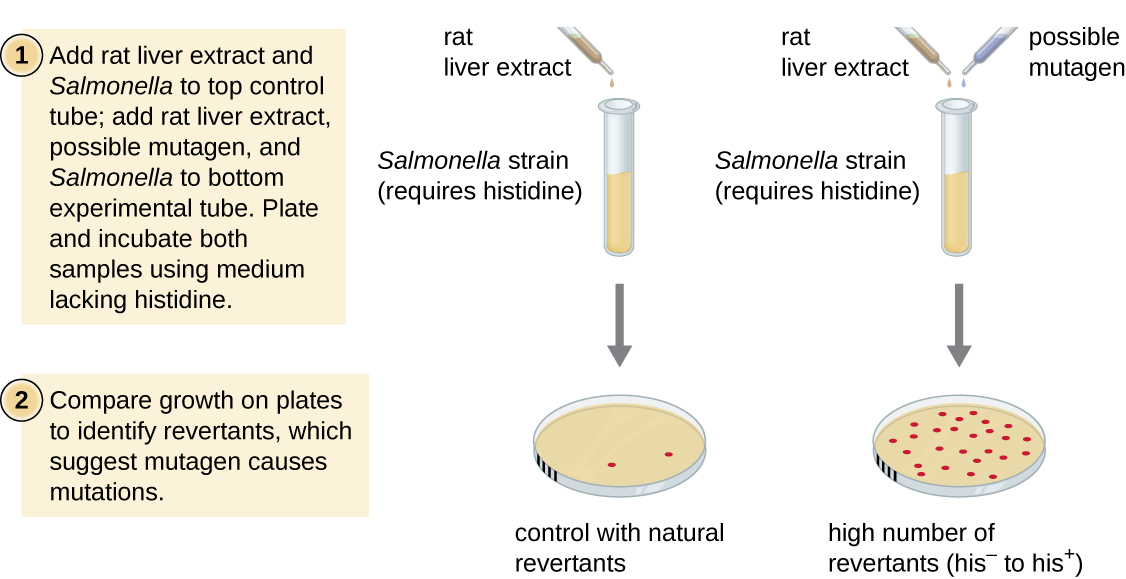

The Ames test, developed by Bruce Ames (1928–) in the 1970s, is a method that uses bacteria for rapid, inexpensive screening of the carcinogenic potential of new chemical compounds. The test measures the mutation rate associated with exposure to the compound, which, if elevated, may indicate that exposure to this compound is associated with greater cancer risk. The Ames test uses as the test organism a strain of Salmonella typhimurium that is a histidine auxotroph, unable to synthesize its own histidine because of a mutation in an essential gene required for its synthesis. After exposure to a potential mutagen, these bacteria are plated onto a medium lacking histidine, and the number of mutants regaining the ability to synthesize histidine is recorded and compared with the number of such mutants that arise in the absence of the potential mutagen ([link]). Chemicals that are more mutagenic will bring about more mutants with restored histidine synthesis in the Ames test. Because many chemicals are not directly mutagenic but are metabolized to mutagenic forms by liver enzymes, rat liver extract is commonly included at the start of this experiment to mimic liver metabolism. After the Ames test is conducted, compounds identified as mutagenic are further tested for their potential carcinogenic properties by using other models, including animal models like mice and rats.

Which of the following is a change in the sequence that leads to formation of a stop codon?

B

The formation of pyrimidine dimers results from which of the following?

C

Which of the following is an example of a frameshift mutation?

D

Which of the following is the type of DNA repair in which thymine dimers are directly broken down by the enzyme photolyase?

A

Which of the following regarding the Ames test is true?

B

A chemical mutagen that is structurally similar to a nucleotide but has different base-pairing rules is called a ________.

nucleoside analog

The enzyme used in light repair to split thymine dimers is called ________.

photolyase

The phenotype of an organism that is most commonly observed in nature is called the ________.

wild type

Carcinogens are typically mutagenic.

True

Why is it more likely that insertions or deletions will be more detrimental to a cell than point mutations?

Below are several DNA sequences that are mutated compared with the wild-type sequence: 3’-T A C T G A C T G A C G A T C-5’. Envision that each is a section of a DNA molecule that has separated in preparation for transcription, so you are only seeing the template strand. Construct the complementary DNA sequences (indicating 5’ and 3’ ends) for each mutated DNA sequence, then transcribe (indicating 5’ and 3’ ends) the template strands, and translate the mRNA molecules using the genetic code, recording the resulting amino acid sequence (indicating the N and C termini). What type of mutation is each?

| Mutated DNA Template Strand #1: 3’-T A C T G T C T G A C G A T C-5’ Complementary DNA sequence: mRNA sequence transcribed from template: Amino acid sequence of peptide: Type of mutation: |

| Mutated DNA Template Strand #2: 3’-T A C G G A C T G A C G A T C-5’ Complementary DNA sequence: mRNA sequence transcribed from template: Amino acid sequence of peptide: Type of mutation: |

| Mutated DNA Template Strand #3: 3’-T A C T G A C T G A C T A T C-5’ Complementary DNA sequence: mRNA sequence transcribed from template: Amino acid sequence of peptide: Type of mutation: |

| Mutated DNA Template Strand #4: 3’-T A C G A C T G A C T A T C-5’ Complementary DNA sequence: mRNA sequence transcribed from template: Amino acid sequence of peptide: Type of mutation: |

Why do you think the Ames test is preferable to the use of animal models to screen chemical compounds for mutagenicity?

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/e42bd376-624b-4c0f-972f-e0c57998e765@5.3

Attribution: