The most abundant biomolecules on earth are carbohydrates. From a chemical viewpoint, carbohydrates are primarily a combination of carbon and water, and many of them have the empirical formula (CH2O)n, where n is the number of repeated units. This view represents these molecules simply as “hydrated” carbon atom chains in which water molecules attach to each carbon atom, leading to the term “carbohydrates.” Although all carbohydrates contain carbon, hydrogen, and oxygen, there are some that also contain nitrogen, phosphorus, and/or sulfur. Carbohydrates have myriad different functions. They are abundant in terrestrial ecosystems, many forms of which we use as food sources. These molecules are also vital parts of macromolecular structures that store and transmit genetic information (i.e., DNA and RNA). They are the basis of biological polymers that impart strength to various structural components of organisms (e.g., cellulose and chitin), and they are the primary source of energy storage in the form of starch and glycogen.

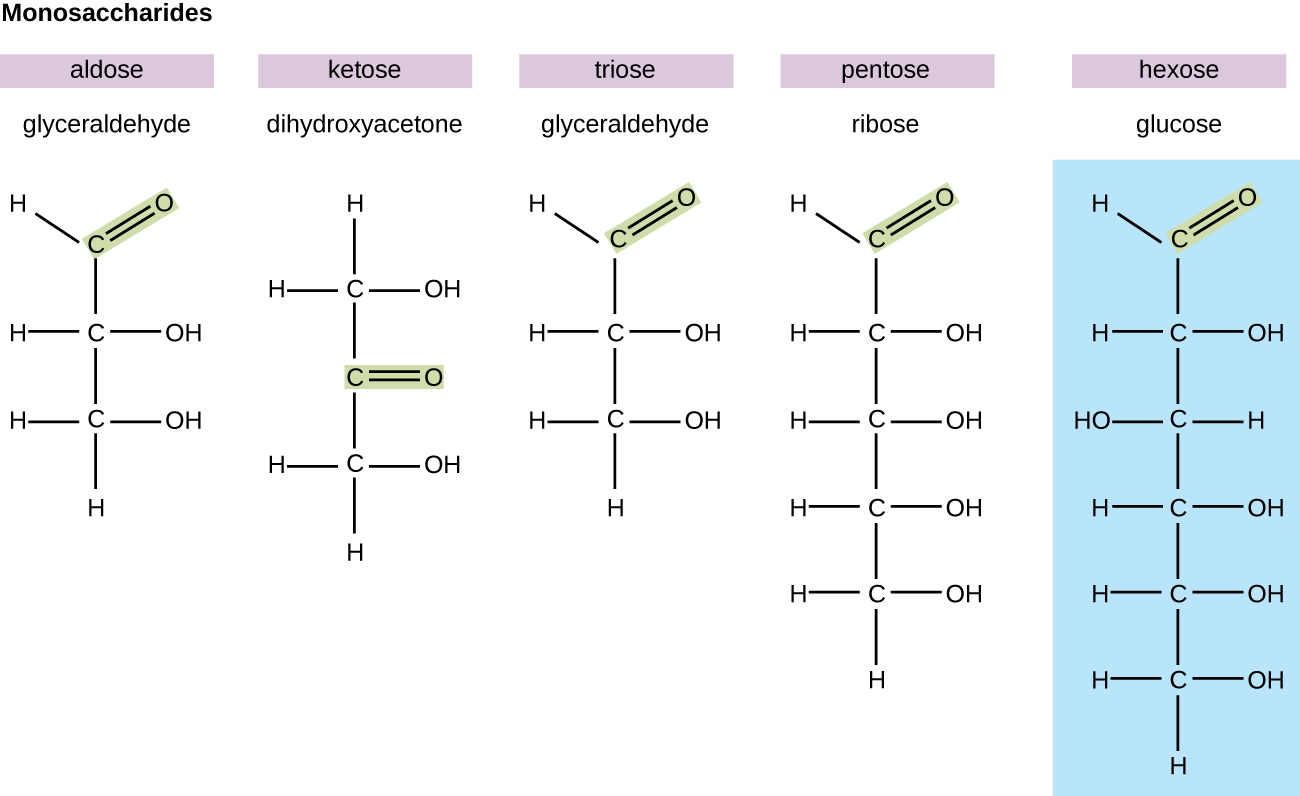

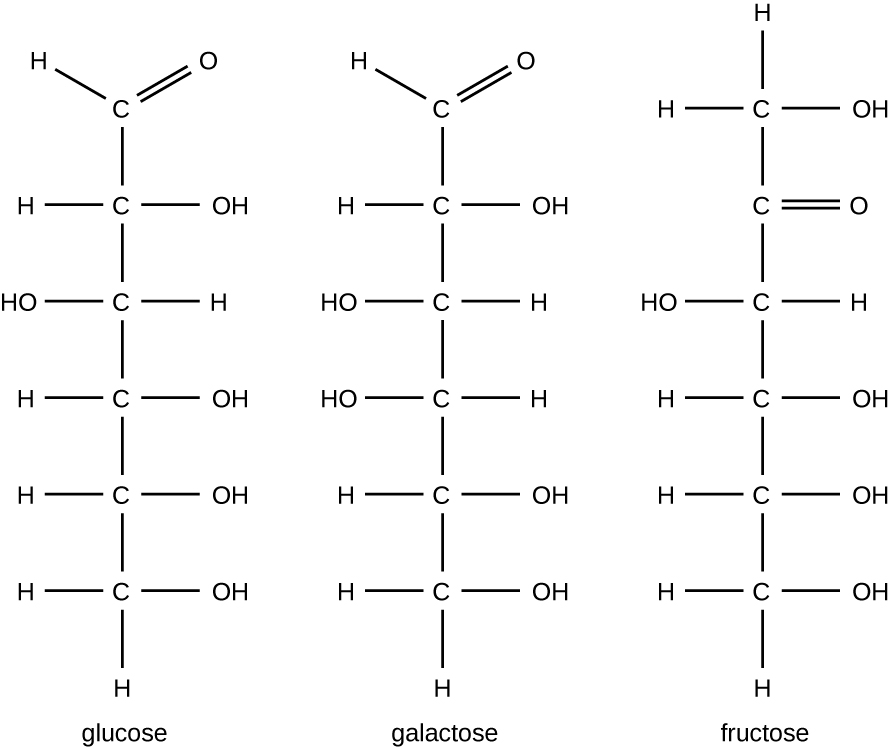

In biochemistry, carbohydrates are often called saccharides, from the Greek sakcharon, meaning sugar, although not all the saccharides are sweet. The simplest carbohydrates are called monosaccharides, or simple sugars. They are the building blocks (monomers) for the synthesis of polymers or complex carbohydrates, as will be discussed further in this section. Monosaccharides are classified based on the number of carbons in the molecule. General categories are identified using a prefix that indicates the number of carbons and the suffix –ose, which indicates a saccharide; for example, triose (three carbons), tetrose (four carbons), pentose (five carbons), and hexose (six carbons) ([link]). The hexose D-glucose is the most abundant monosaccharide in nature. Other very common and abundant hexose monosaccharides are galactose, used to make the disaccharide milk sugar lactose, and the fruit sugar fructose.

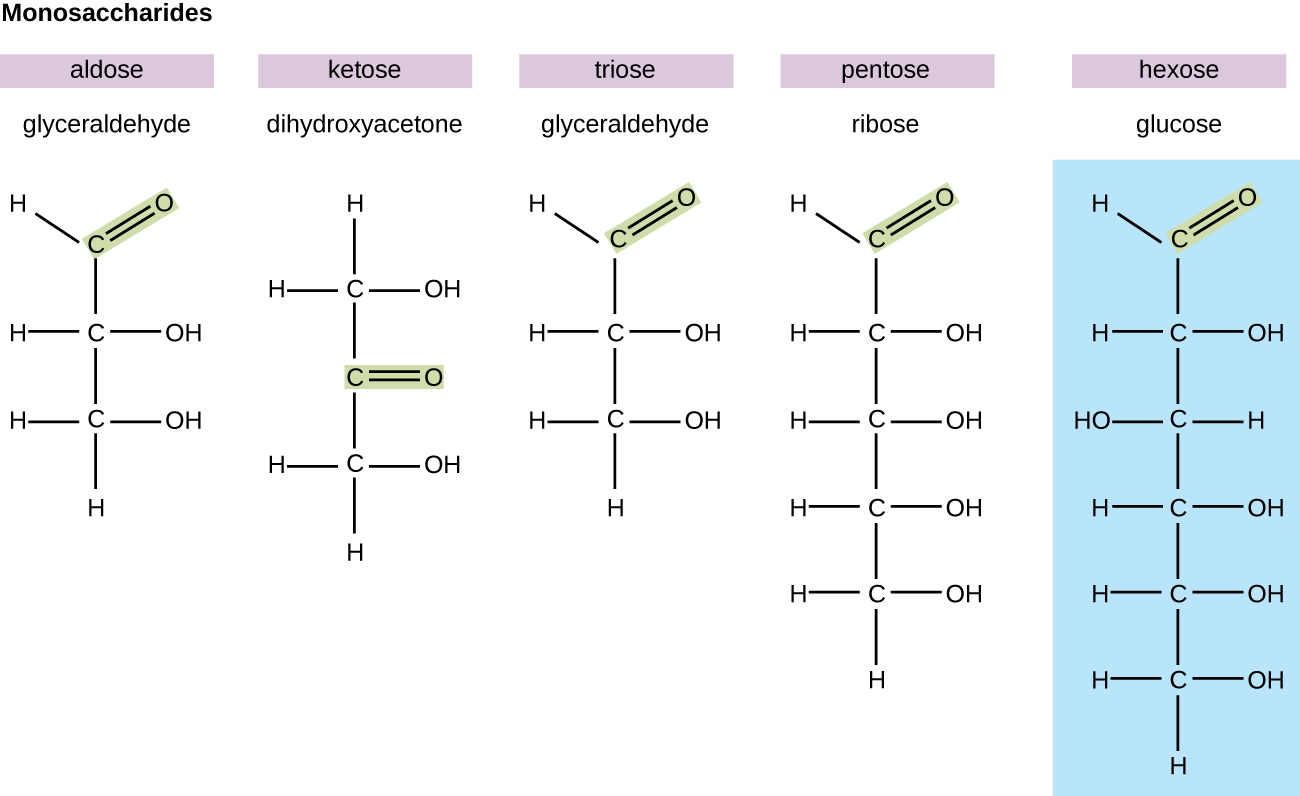

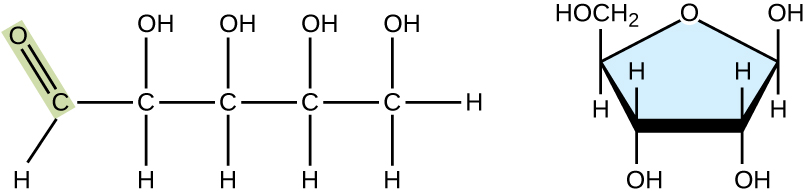

Monosaccharides of four or more carbon atoms are typically more stable when they adopt cyclic, or ring, structures. These ring structures result from a chemical reaction between functional groups on opposite ends of the sugar’s flexible carbon chain, namely the carbonyl group and a relatively distant hydroxyl group. Glucose, for example, forms a six-membered ring ([link]).

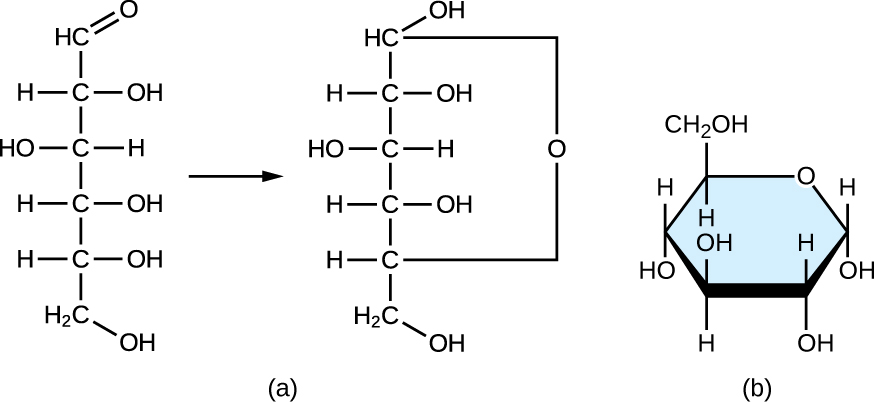

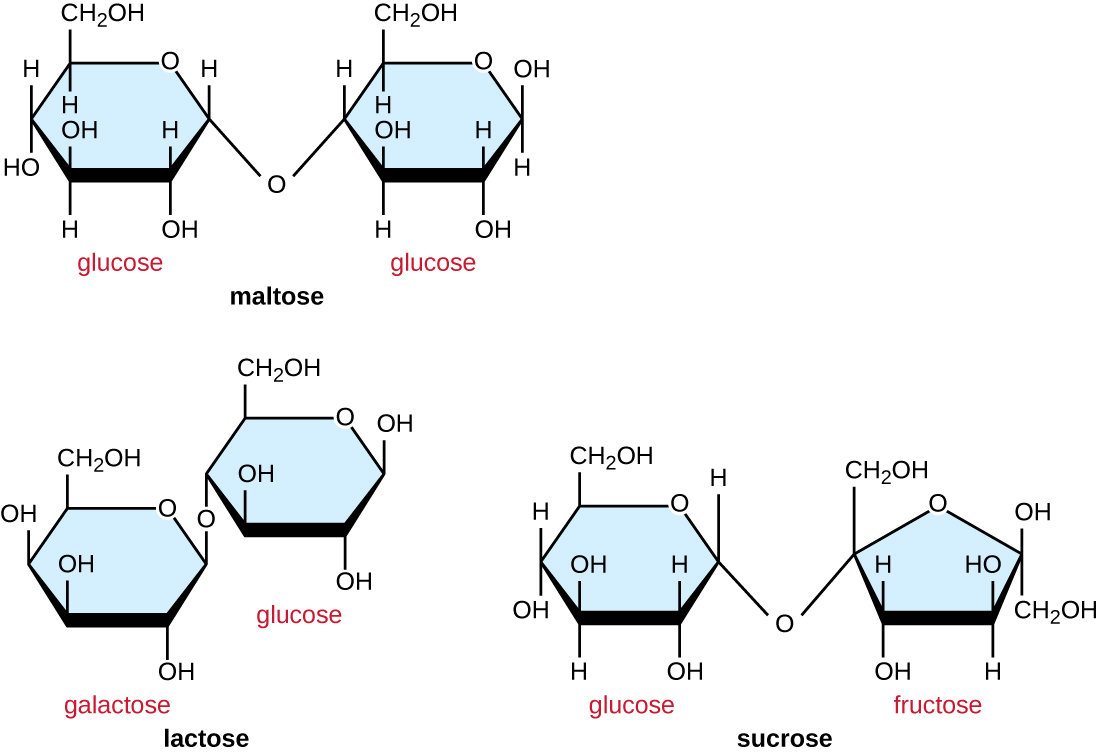

Two monosaccharide molecules may chemically bond to form a disaccharide. The name given to the covalent bond between the two monosaccharides is a glycosidic bond. Glycosidic bonds form between hydroxyl groups of the two saccharide molecules, an example of the dehydration synthesis described in the previous section of this chapter:

Common disaccharides are the grain sugar maltose, made of two glucose molecules; the milk sugar lactose, made of a galactose and a glucose molecule; and the table sugar sucrose, made of a glucose and a fructose molecule ([link]).

Polysaccharides, also called glycans, are large polymers composed of hundreds of monosaccharide monomers. Unlike mono- and disaccharides, polysaccharides are not sweet and, in general, they are not soluble in water. Like disaccharides, the monomeric units of polysaccharides are linked together by glycosidic bonds.

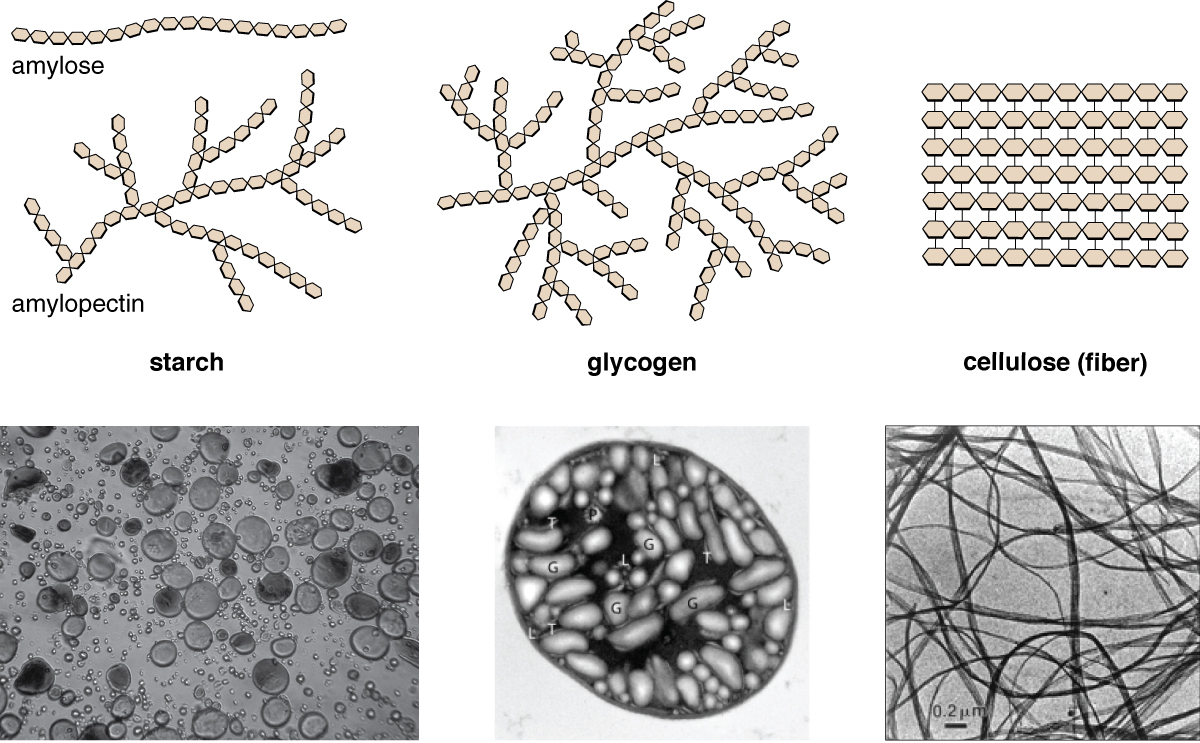

Polysaccharides are very diverse in their structure. Three of the most biologically important polysaccharides—starch, glycogen, and cellulose—are all composed of repetitive glucose units, although they differ in their structure ([link]). Cellulose consists of a linear chain of glucose molecules and is a common structural component of cell walls in plants and other organisms. Glycogen and starch are branched polymers; glycogen is the primary energy-storage molecule in animals and bacteria, whereas plants primarily store energy in starch. The orientation of the glycosidic linkages in these three polymers is different as well and, as a consequence, linear and branched macromolecules have different properties.

Modified glucose molecules can be fundamental components of other structural polysaccharides. Examples of these types of structural polysaccharides are N-acetyl glucosamine (NAG) and N-acetyl muramic acid (NAM) found in bacterial cell wall peptidoglycan. Polymers of NAG form chitin, which is found in fungal cell walls and in the exoskeleton of insects.

By definition, carbohydrates contain which elements?

C

Monosaccharides may link together to form polysaccharides by forming which type of bond?

D

Match each polysaccharide with its description.

| ___chitin | A. energy storage polymer in plants | {: valign=”top”}| ___glycogen | B. structural polymer found in plants | {: valign=”top”}| ___starch | C. structural polymer found in cell walls of fungi and exoskeletons of some animals | {: valign=”top”}| ___cellulose | D. energy storage polymer found in animal cells and bacteria | {: valign=”top”}{: summary=”No Summary” .unnumbered .unstyled}

C, D, A, B

What are monosaccharides, disaccharides, and polysaccharides?

The figure depicts the structural formulas of glucose, galactose, and fructose. (a) Circle the functional groups that classify the sugars either an aldose or a ketose, and identify each sugar as one or the other. (b) The chemical formula of these compounds is the same, although the structural formula is different. What are such compounds called?

Structural diagrams for the linear and cyclic forms of a monosaccharide are shown. (a) What is the molecular formula for this monosaccharide? (Count the C, H and O atoms in each to confirm that these two molecules have the same formula, and report this formula.) (b) Identify which hydroxyl group in the linear structure undergoes the ring-forming reaction with the carbonyl group.

The term “dextrose” is commonly used in medical settings when referring to the biologically relevant isomer of the monosaccharide glucose. Explain the logic of this alternative name.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/e42bd376-624b-4c0f-972f-e0c57998e765@5.3

Attribution: