We have examined several versions of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus in higher dimensions that relate the integral around an oriented boundary of a domain to a “derivative” of that entity on the oriented domain. In this section, we state the divergence theorem, which is the final theorem of this type that we will study. The divergence theorem has many uses in physics; in particular, the divergence theorem is used in the field of partial differential equations to derive equations modeling heat flow and conservation of mass. We use the theorem to calculate flux integrals and apply it to electrostatic fields.

Before examining the divergence theorem, it is helpful to begin with an overview of the versions of the Fundamental Theorem of Calculus we have discussed:

This theorem relates the integral of derivative

over line segment

along the x-axis to a difference of

evaluated on the boundary.

where

is the initial point of C and

is the terminal point of C. The Fundamental Theorem for Line Integrals allows path C to be a path in a plane or in space, not just a line segment on the x-axis. If we think of the gradient as a derivative, then this theorem relates an integral of derivative

over path C to a difference of

evaluated on the boundary of C.

Since

and curl is a derivative of sorts, Green’s theorem relates the integral of derivative curlF over planar region D to an integral of F over the boundary of D.

Since

and divergence is a derivative of sorts, the flux form of Green’s theorem relates the integral of derivative divF over planar region D to an integral of F over the boundary of D.

If we think of the curl as a derivative of sorts, then Stokes’ theorem relates the integral of derivative curlF over surface S (not necessarily planar) to an integral of F over the boundary of S.

The divergence theorem follows the general pattern of these other theorems. If we think of divergence as a derivative of sorts, then the divergence theorem relates a triple integral of derivative divF over a solid to a flux integral of F over the boundary of the solid. More specifically, the divergence theorem relates a flux integral of vector field F over a closed surface S to a triple integral of the divergence of F over the solid enclosed by S.

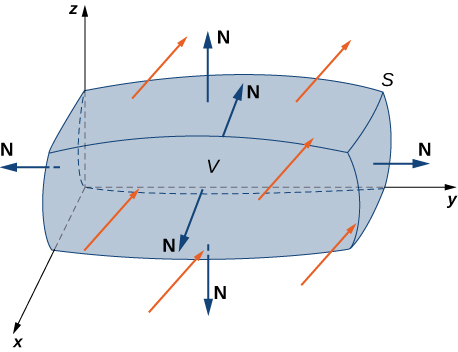

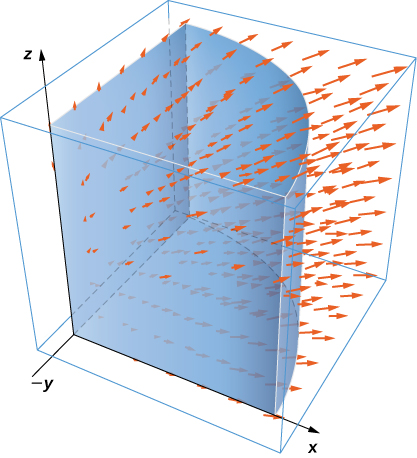

Let S be a piecewise, smooth closed surface that encloses solid E in space. Assume that S is oriented outward, and let F be a vector field with continuous partial derivatives on an open region containing E ([link]). Then

Recall that the flux form of Green’s theorem states that

Therefore, the divergence theorem is a version of Green’s theorem in one higher dimension.

The proof of the divergence theorem is beyond the scope of this text. However, we look at an informal proof that gives a general feel for why the theorem is true, but does not prove the theorem with full rigor. This explanation follows the informal explanation given for why Stokes’ theorem is true.

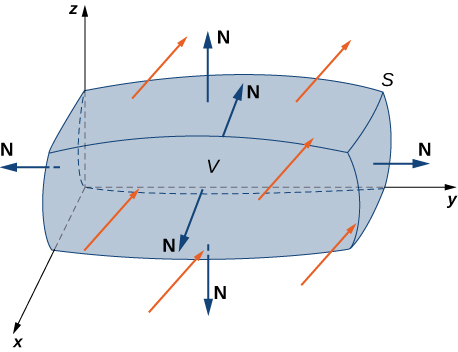

Let B be a small box with sides parallel to the coordinate planes inside E ([link]). Let the center of B have coordinates

and suppose the edge lengths are

and

([link](b)). The normal vector out of the top of the box is k and the normal vector out of the bottom of the box is

The dot product of

with k is R and the dot product with

is

The area of the top of the box (and the bottom of the box)

is

The flux out of the top of the box can be approximated by

([link](c)) and the flux out of the bottom of the box is

If we denote the difference between these values as

then the net flux in the vertical direction can be approximated by

However,

Therefore, the net flux in the vertical direction can be approximated by

Similarly, the net flux in the x-direction can be approximated by

and the net flux in the y-direction can be approximated by

Adding the fluxes in all three directions gives an approximation of the total flux out of the box:

This approximation becomes arbitrarily close to the value of the total flux as the volume of the box shrinks to zero.

The sum of

over all the small boxes approximating E is approximately

On the other hand, the sum of

over all the small boxes approximating E is the sum of the fluxes over all these boxes. Just as in the informal proof of Stokes’ theorem, adding these fluxes over all the boxes results in the cancelation of a lot of the terms. If an approximating box shares a face with another approximating box, then the flux over one face is the negative of the flux over the shared face of the adjacent box. These two integrals cancel out. When adding up all the fluxes, the only flux integrals that survive are the integrals over the faces approximating the boundary of E. As the volumes of the approximating boxes shrink to zero, this approximation becomes arbitrarily close to the flux over S.

□

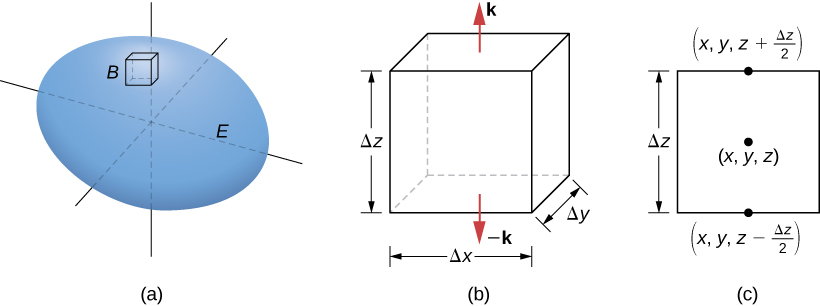

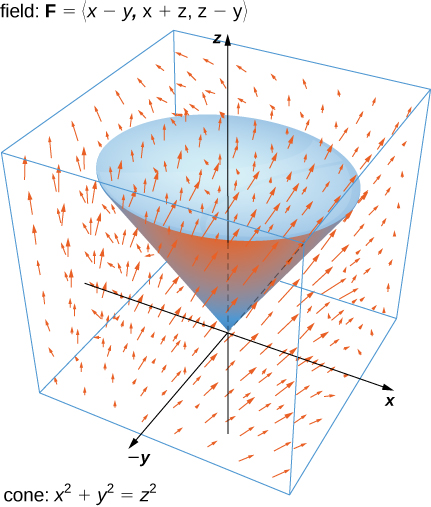

Verify the divergence theorem for vector field

and surface S that consists of cone

and the circular top of the cone (see the following figure). Assume this surface is positively oriented.

Let E be the solid cone enclosed by S. To verify the theorem for this example, we show that

by calculating each integral separately.

To compute the triple integral, note that

and therefore the triple integral is

The volume of a right circular cone is given by

In this case,

Therefore,

To compute the flux integral, first note that S is piecewise smooth; S can be written as a union of smooth surfaces. Therefore, we break the flux integral into two pieces: one flux integral across the circular top of the cone and one flux integral across the remaining portion of the cone. Call the circular top

and the portion under the top

We start by calculating the flux across the circular top of the cone. Notice that

has parameterization

Then, the tangent vectors are

and

Therefore, the flux across

is

We now calculate the flux over

A parameterization of this surface is

The tangent vectors are

and

so the cross product is

Notice that the negative signs on the x and y components induce the negative (or inward) orientation of the cone. Since the surface is positively oriented, we use vector

in the flux integral. The flux across

is then

The total flux across S is

and we have verified the divergence theorem for this example.

Verify the divergence theorem for vector field

and surface S given by the cylinder

plus the circular top and bottom of the cylinder. Assume that S is positively oriented.

Both integrals equal

Calculate both the flux integral and the triple integral with the divergence theorem and verify they are equal.

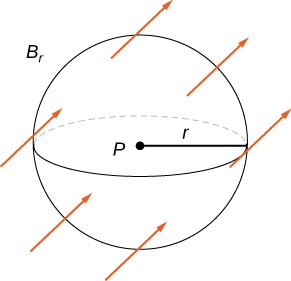

Recall that the divergence of continuous field F at point P is a measure of the “outflowing-ness” of the field at P. If F represents the velocity field of a fluid, then the divergence can be thought of as the rate per unit volume of the fluid flowing out less the rate per unit volume flowing in. The divergence theorem confirms this interpretation. To see this, let P be a point and let

be a ball of small radius r centered at P ([link]). Let

be the boundary sphere of

Since the radius is small and F is continuous,

for all other points Q in the ball. Therefore, the flux across

can be approximated using the divergence theorem:

Since

is a constant,

Therefore, flux

can be approximated by

This approximation gets better as the radius shrinks to zero, and therefore

This equation says that the divergence at P is the net rate of outward flux of the fluid per unit volume.

The divergence theorem translates between the flux integral of closed surface S and a triple integral over the solid enclosed by S. Therefore, the theorem allows us to compute flux integrals or triple integrals that would ordinarily be difficult to compute by translating the flux integral into a triple integral and vice versa.

Calculate the surface integral

where S is cylinder

including the circular top and bottom, and

We could calculate this integral without the divergence theorem, but the calculation is not straightforward because we would have to break the flux integral into three separate integrals: one for the top of the cylinder, one for the bottom, and one for the side. Furthermore, each integral would require parameterizing the corresponding surface, calculating tangent vectors and their cross product, and using [link].

By contrast, the divergence theorem allows us to calculate the single triple integral

where E is the solid enclosed by the cylinder. Using the divergence theorem and converting to cylindrical coordinates, we have

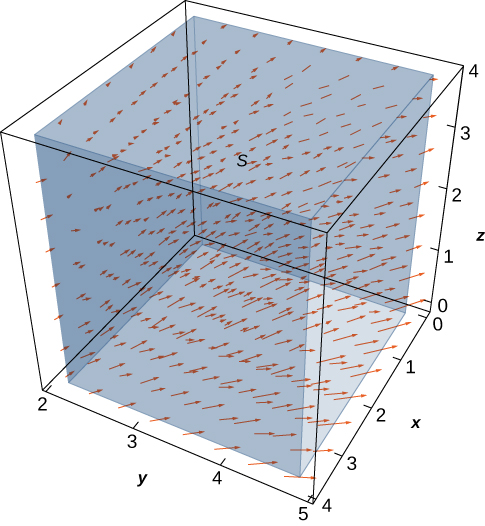

Use the divergence theorem to calculate flux integral

where S is the boundary of the box given by

and

(see the following figure).

30

Calculate the corresponding triple integral.

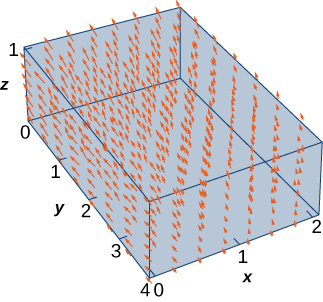

Let

be the velocity field of a fluid. Let C be the solid cube given by

and let S be the boundary of this cube (see the following figure). Find the flow rate of the fluid across S.

The flow rate of the fluid across S is

Before calculating this flux integral, let’s discuss what the value of the integral should be. Based on [link], we see that if we place this cube in the fluid (as long as the cube doesn’t encompass the origin), then the rate of fluid entering the cube is the same as the rate of fluid exiting the cube. The field is rotational in nature and, for a given circle parallel to the xy-plane that has a center on the z-axis, the vectors along that circle are all the same magnitude. That is how we can see that the flow rate is the same entering and exiting the cube. The flow into the cube cancels with the flow out of the cube, and therefore the flow rate of the fluid across the cube should be zero.

To verify this intuition, we need to calculate the flux integral. Calculating the flux integral directly requires breaking the flux integral into six separate flux integrals, one for each face of the cube. We also need to find tangent vectors, compute their cross product, and use [link]. However, using the divergence theorem makes this calculation go much more quickly:

Therefore the flux is zero, as expected.

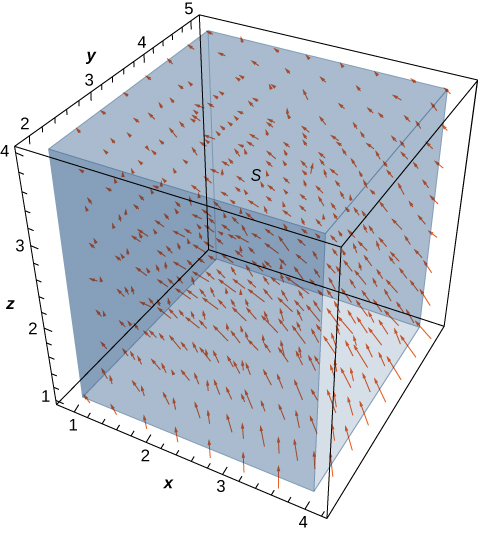

Let

be the velocity field of a fluid. Let C be the solid cube given by

and let S be the boundary of this cube (see the following figure). Find the flow rate of the fluid across S.

Use the divergence theorem and calculate a triple integral.

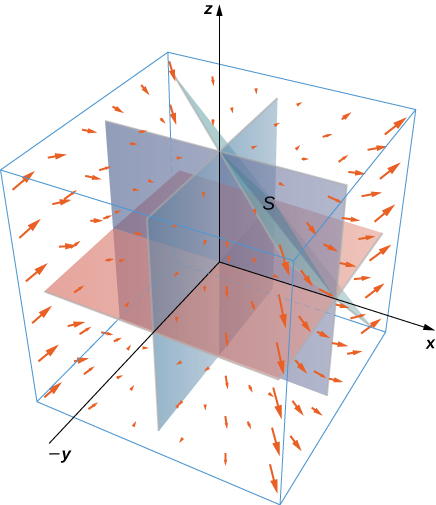

[link] illustrates a remarkable consequence of the divergence theorem. Let S be a piecewise, smooth closed surface and let F be a vector field defined on an open region containing the surface enclosed by S. If F has the form

then the divergence of F is zero. By the divergence theorem, the flux of F across S is also zero. This makes certain flux integrals incredibly easy to calculate. For example, suppose we wanted to calculate the flux integral

where S is a cube and

Calculating the flux integral directly would be difficult, if not impossible, using techniques we studied previously. At the very least, we would have to break the flux integral into six integrals, one for each face of the cube. But, because the divergence of this field is zero, the divergence theorem immediately shows that the flux integral is zero.

We can now use the divergence theorem to justify the physical interpretation of divergence that we discussed earlier. Recall that if F is a continuous three-dimensional vector field and P is a point in the domain of F, then the divergence of F at P is a measure of the “outflowing-ness” of F at P. If F represents the velocity field of a fluid, then the divergence of F at P is a measure of the net flow rate out of point P (the flow of fluid out of P less the flow of fluid in to P). To see how the divergence theorem justifies this interpretation, let

be a ball of very small radius r with center P, and assume that

is in the domain of F. Furthermore, assume that

has a positive, outward orientation. Since the radius of

is small and F is continuous, the divergence of F is approximately constant on

That is, if

is any point in

then

Let

denote the boundary sphere of

We can approximate the flux across

using the divergence theorem as follows:

As we shrink the radius r to zero via a limit, the quantity

gets arbitrarily close to the flux. Therefore,

and we can consider the divergence at P as measuring the net rate of outward flux per unit volume at P. Since “outflowing-ness” is an informal term for the net rate of outward flux per unit volume, we have justified the physical interpretation of divergence we discussed earlier, and we have used the divergence theorem to give this justification.

The divergence theorem has many applications in physics and engineering. It allows us to write many physical laws in both an integral form and a differential form (in much the same way that Stokes’ theorem allowed us to translate between an integral and differential form of Faraday’s law). Areas of study such as fluid dynamics, electromagnetism, and quantum mechanics have equations that describe the conservation of mass, momentum, or energy, and the divergence theorem allows us to give these equations in both integral and differential forms.

One of the most common applications of the divergence theorem is to electrostatic fields. An important result in this subject is Gauss’ law. This law states that if S is a closed surface in electrostatic field E, then the flux of E across S is the total charge enclosed by S (divided by an electric constant). We now use the divergence theorem to justify the special case of this law in which the electrostatic field is generated by a stationary point charge at the origin.

If

is a point in space, then the distance from the point to the origin is

Let

denote radial vector field

The vector at a given position in space points in the direction of unit radial vector

and is scaled by the quantity

Therefore, the magnitude of a vector at a given point is inversely proportional to the square of the vector’s distance from the origin. Suppose we have a stationary charge of q Coulombs at the origin, existing in a vacuum. The charge generates electrostatic field E given by

where the approximation

farad (F)/m is an electric constant. (The constant

is a measure of the resistance encountered when forming an electric field in a vacuum.) Notice that E is a radial vector field similar to the gravitational field described in [link]. The difference is that this field points outward whereas the gravitational field points inward. Because

we say that electrostatic fields obey an inverse-square law. That is, the electrostatic force at a given point is inversely proportional to the square of the distance from the source of the charge (which in this case is at the origin). Given this vector field, we show that the flux across closed surface S is zero if the charge is outside of S, and that the flux is

if the charge is inside of S. In other words, the flux across S is the charge inside the surface divided by constant

This is a special case of Gauss’ law, and here we use the divergence theorem to justify this special case.

To show that the flux across S is the charge inside the surface divided by constant

we need two intermediate steps. First we show that the divergence of

is zero and then we show that the flux of

across any smooth surface S is either zero or

We can then justify this special case of Gauss’ law.

Verify that the divergence of

is zero where

is defined (away from the origin).

Since

the quotient rule gives us

Similarly,

Therefore,

Notice that since the divergence of

is zero and E is

scaled by a constant, the divergence of electrostatic field E is also zero (except at the origin).

Let S be a connected, piecewise smooth closed surface and let

Then,

In other words, this theorem says that the flux of

across any piecewise smooth closed surface S depends only on whether the origin is inside of S.

The logic of this proof follows the logic of [link], only we use the divergence theorem rather than Green’s theorem.

First, suppose that S does not encompass the origin. In this case, the solid enclosed by S is in the domain of

and since the divergence of

is zero, we can immediately apply the divergence theorem and find that

is zero.

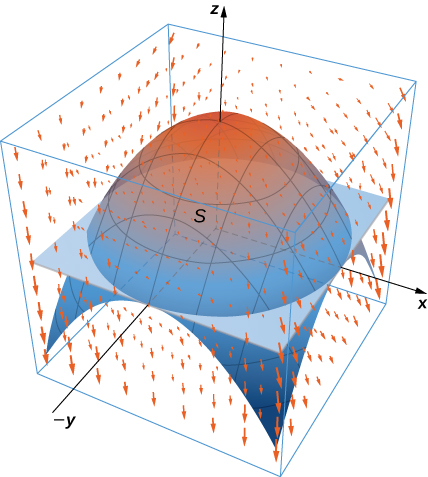

Now suppose that S does encompass the origin. We cannot just use the divergence theorem to calculate the flux, because the field is not defined at the origin. Let

be a sphere of radius a inside of S centered at the origin. The outward normal vector field on the sphere, in spherical coordinates, is

(see [link]). Therefore, on the surface of the sphere, the dot product

(in spherical coordinates) is

The flux of

across

is

Now, remember that we are interested in the flux across S, not necessarily the flux across

To calculate the flux across S, let E be the solid between surfaces

and S. Then, the boundary of E consists of

and S. Denote this boundary by

to indicate that S is oriented outward but now

is oriented inward. We would like to apply the divergence theorem to solid E. Notice that the divergence theorem, as stated, can’t handle a solid such as E because E has a hole. However, the divergence theorem can be extended to handle solids with holes, just as Green’s theorem can be extended to handle regions with holes. This allows us to use the divergence theorem in the following way. By the divergence theorem,

Therefore,

and we have our desired result.

□

Now we return to calculating the flux across a smooth surface in the context of electrostatic field

of a point charge at the origin. Let S be a piecewise smooth closed surface that encompasses the origin. Then

If S does not encompass the origin, then

Therefore, we have justified the claim that we set out to justify: the flux across closed surface S is zero if the charge is outside of S, and the flux is

if the charge is inside of S.

This analysis works only if there is a single point charge at the origin. In this case, Gauss’ law says that the flux of E across S is the total charge enclosed by S. Gauss’ law can be extended to handle multiple charged solids in space, not just a single point charge at the origin. The logic is similar to the previous analysis, but beyond the scope of this text. In full generality, Gauss’ law states that if S is a piecewise smooth closed surface and Q is the total amount of charge inside of S, then the flux of E across S is

Suppose we have four stationary point charges in space, all with a charge of 0.002 Coulombs (C). The charges are located at

Let E denote the electrostatic field generated by these point charges. If S is the sphere of radius 2 oriented outward and centered at the origin, then find

According to Gauss’ law, the flux of E across S is the total charge inside of S divided by the electric constant. Since S has radius 2, notice that only two of the charges are inside of S: the charge at

and the charge at

Therefore, the total charge encompassed by S is 0.004 and, by Gauss’ law,

Work the previous example for surface S that is a sphere of radius 4 centered at the origin, oriented outward.

Use Gauss’ law.

For the following exercises, use a computer algebraic system (CAS) and the divergence theorem to evaluate surface integral

for the given choice of F and the boundary surface S. For each closed surface, assume N is the outward unit normal vector.

[T]

S is the surface of cube

[T]

S is the surface of hemisphere

together with disk

in the xy-plane.

[T]

S is the surface of the five faces of unit cube

[T]

S is the surface of paraboloid

[T]

S is the surface of sphere

[T]

S is the surface of the solid bounded by cylinder

and planes

[T]

S is the surface bounded above by sphere

and below by cone

in spherical coordinates. (Think of S as the surface of an “ice cream cone.”)

[T]

S is the surface bounded by cylinder

and planes

[T] Surface integral

where S is the solid bounded by paraboloid

and plane

and

Use the divergence theorem to calculate surface integral

where

and S is upper hemisphere

oriented upward.

Use the divergence theorem to calculate surface integral

where

and S is the surface bounded by cylinder

and planes

and

Use the divergence theorem to calculate surface integral

when

and S is the surface of the box with vertices

Use the divergence theorem to calculate surface integral

when

and S is a part of paraboloid

that lies above plane

and is oriented upward.

[T] Use a CAS and the divergence theorem to calculate flux

where

and S is a sphere with center (0, 0) and radius 2.

Use the divergence theorem to compute the value of flux integral

where

and S is the area of the region bounded by

Use the divergence theorem to compute flux integral

where

and S consists of the union of paraboloid

and disk

oriented outward. What is the flux through just the paraboloid?

Use the divergence theorem to compute flux integral

where

and S is a part of cone

beneath top plane

oriented downward.

Use the divergence theorem to calculate surface integral

for

where S is the surface bounded by cylinder

and planes

Consider

Let E be the solid enclosed by paraboloid

and plane

with normal vectors pointing outside E. Compute flux F across the boundary of E using the divergence theorem.

For the following exercises, use a CAS along with the divergence theorem to compute the net outward flux for the fields across the given surfaces S.

[T]

S is sphere

[T]

S is the boundary of the tetrahedron in the first octant formed by plane

[T]

S is sphere

[T]

S is the surface of paraboloid

for

plus its base in the xy-plane.

For the following exercises, use a CAS and the divergence theorem to compute the net outward flux for the vector fields across the boundary of the given regions D.

[T]

D is the region between spheres of radius 2 and 4 centered at the origin.

[T]

D is the region between spheres of radius 1 and 2 centered at the origin.

[T]

D is the region in the first octant between planes

and

20

Let

Use the divergence theorem to calculate

where S is the surface of the cube with corners at

oriented outward.

Use the divergence theorem to find the outward flux of field

through the cube bounded by planes

Let

and let S be hemisphere

together with disk

in the xy-plane. Use the divergence theorem.

Evaluate

where

and S is the surface consisting of all faces except the tetrahedron bounded by plane

and the coordinate planes, with outward unit normal vector N.

Find the net outward flux of field

across any smooth closed surface in

where a, b, and c are constants.

Use the divergence theorem to evaluate

where

and S is sphere

with constant

Use the divergence theorem to evaluate

where

and S is the boundary of the cube defined by

Let R be the region defined by

Use the divergence theorem to find

Let E be the solid bounded by the xy-plane and paraboloid

so that S is the surface of the paraboloid piece together with the disk in the xy-plane that forms its bottom. If

find

using the divergence theorem.

Let E be the solid unit cube with diagonally opposite corners at the origin and (1, 1, 1), and faces parallel to the coordinate planes. Let S be the surface of E, oriented with the outward-pointing normal. Use a CAS to find

using the divergence theorem if

Use the divergence theorem to calculate the flux of

through sphere

Find

where

and S is the outwardly oriented surface obtained by removing cube

from cube

Consider radial vector field

Compute the surface integral, where S is the surface of a sphere of radius a centered at the origin.

Compute the flux of water through parabolic cylinder

from

if the velocity vector is

[T] Use a CAS to find the flux of vector field

across the portion of hyperboloid

between planes

and

oriented so the unit normal vector points away from the z-axis.

[T] Use a CAS to find the flux of vector field

through surface S, where S is given by

from

oriented so the unit normal vector points downward.

[T] Use a CAS to compute

where

and S is a part of sphere

with

Evaluate

where

and S is a closed surface bounding the region and consisting of solid cylinder

and

[T] Use a CAS to calculate the flux of

across surface S, where S is the boundary of the solid bounded by hemispheres

and

and plane

Use the divergence theorem to evaluate

where

and S is the surface consisting of three pieces:

on the top;

on the sides; and

on the bottom.

[T] Use a CAS and the divergence theorem to evaluate

where

and S is sphere

orientated outward.

Use the divergence theorem to evaluate

where

and S is the boundary of the solid enclosed by paraboloid

cylinder

and plane

and S is oriented outward.

For the following exercises, Fourier’s law of heat transfer states that the heat flow vector F at a point is proportional to the negative gradient of the temperature; that is,

which means that heat energy flows hot regions to cold regions. The constant

is called the conductivity, which has metric units of joules per meter per second-kelvin or watts per meter-kelvin. A temperature function for region D is given. Use the divergence theorem to find net outward heat flux

across the boundary S of D, where

D is the sphere of radius a centered at the origin.

True or False? Justify your answer with a proof or a counterexample.

Vector field

is conservative.

False

For vector field

if

in open region

then

The divergence of a vector field is a vector field.

False

If

then

is a conservative vector field.

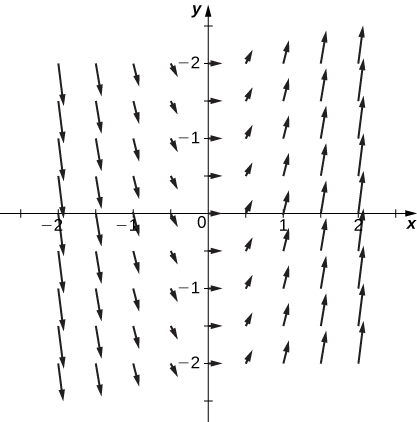

Draw the following vector fields.

Are the following the vector fields conservative? If so, find the potential function

such that

Conservative,

Conservative,

Evaluate the following integrals.

along

from (0, 0) to (4, 2)

where

where S is surface

Find the divergence and curl for the following vector fields.

Divergence:

curl:

Use Green’s theorem to evaluate the following integrals.

where C is a square with vertices (0, 0), (0, 2), (2, 2) and (2, 0)

where C is a circle centered at the origin with radius 3

Use Stokes’ theorem to evaluate

where

is the upper half of the unit sphere

where

is the upward-facing paraboloid

lying in cylinder

Use the divergence theorem to evaluate

over cube

defined by

where

is bounded by paraboloid

and plane

Find the amount of work performed by a 50-kg woman ascending a helical staircase with radius 2 m and height 100 m. The woman completes five revolutions during the climb.

Find the total mass of a thin wire in the shape of a semicircle with radius

and a density function of

Find the total mass of a thin sheet in the shape of a hemisphere with radius 2 for

with a density function

Use the divergence theorem to compute the value of the flux integral over the unit sphere with

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: