Vector fields are an important tool for describing many physical concepts, such as gravitation and electromagnetism, which affect the behavior of objects over a large region of a plane or of space. They are also useful for dealing with large-scale behavior such as atmospheric storms or deep-sea ocean currents. In this section, we examine the basic definitions and graphs of vector fields so we can study them in more detail in the rest of this chapter.

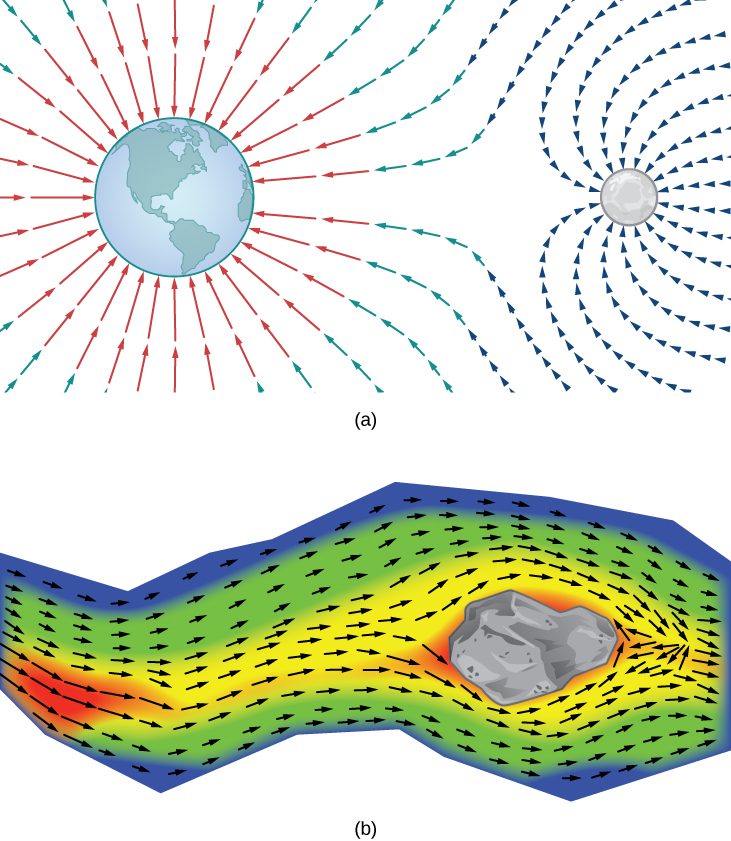

How can we model the gravitational force exerted by multiple astronomical objects? How can we model the velocity of water particles on the surface of a river? [link] gives visual representations of such phenomena.

[link](a) shows a gravitational field exerted by two astronomical objects, such as a star and a planet or a planet and a moon. At any point in the figure, the vector associated with a point gives the net gravitational force exerted by the two objects on an object of unit mass. The vectors of largest magnitude in the figure are the vectors closest to the larger object. The larger object has greater mass, so it exerts a gravitational force of greater magnitude than the smaller object.

[link](b) shows the velocity of a river at points on its surface. The vector associated with a given point on the river’s surface gives the velocity of the water at that point. Since the vectors to the left of the figure are small in magnitude, the water is flowing slowly on that part of the surface. As the water moves from left to right, it encounters some rapids around a rock. The speed of the water increases, and a whirlpool occurs in part of the rapids.

Each figure illustrates an example of a vector field. Intuitively, a vector field is a map of vectors. In this section, we study vector fields in

and

A vector field

in

is an assignment of a two-dimensional vector

to each point

of a subset D of

The subset D is the domain of the vector field.

A vector field F in

is an assignment of a three-dimensional vector

to each point

of a subset D of

The subset D is the domain of the vector field.

A vector field in

can be represented in either of two equivalent ways. The first way is to use a vector with components that are two-variable functions:

The second way is to use the standard unit vectors:

A vector field is said to be continuous if its component functions are continuous.

Let

be a vector field in

Note that this is an example of a continuous vector field since both component functions are continuous. What vector is associated with point

Substitute the point values for x and y:

Let

be a vector field in

What vector is associated with the point

Substitute the point values into the vector function.

We can now represent a vector field in terms of its components of functions or unit vectors, but representing it visually by sketching it is more complex because the domain of a vector field is in

as is the range. Therefore the “graph” of a vector field in

lives in four-dimensional space. Since we cannot represent four-dimensional space visually, we instead draw vector fields in

in a plane itself. To do this, draw the vector associated with a given point at the point in a plane. For example, suppose the vector associated with point

is

Then, we would draw vector

at point

We should plot enough vectors to see the general shape, but not so many that the sketch becomes a jumbled mess. If we were to plot the image vector at each point in the region, it would fill the region completely and is useless. Instead, we can choose points at the intersections of grid lines and plot a sample of several vectors from each quadrant of a rectangular coordinate system in

There are two types of vector fields in

on which this chapter focuses: radial fields and rotational fields. Radial fields model certain gravitational fields and energy source fields, and rotational fields model the movement of a fluid in a vortex. In a radial field, all vectors either point directly toward or directly away from the origin. Furthermore, the magnitude of any vector depends only on its distance from the origin. In a radial field, the vector located at point

is perpendicular to the circle centered at the origin that contains point

and all other vectors on this circle have the same magnitude.

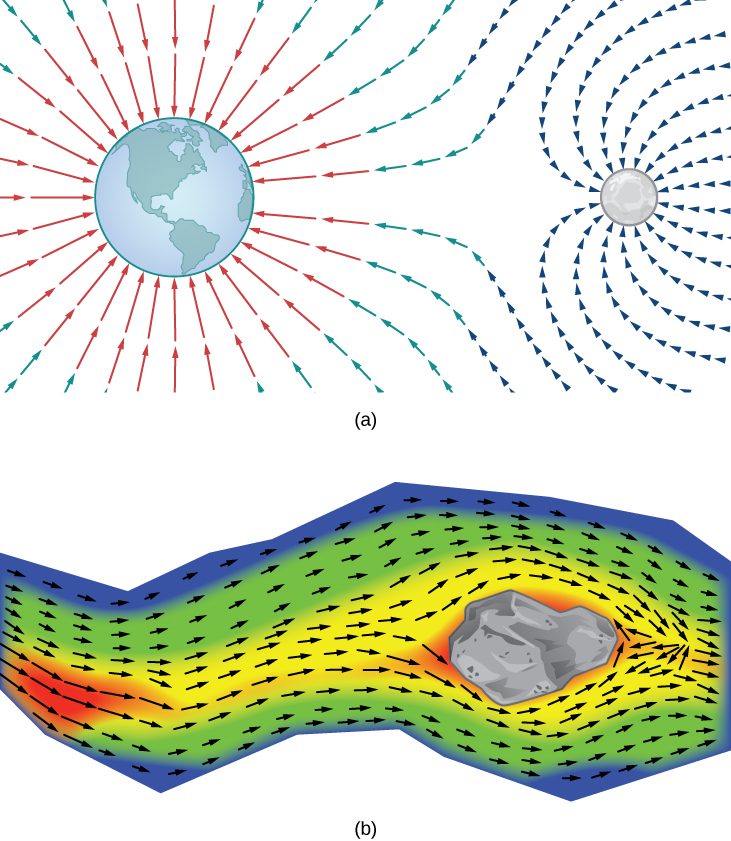

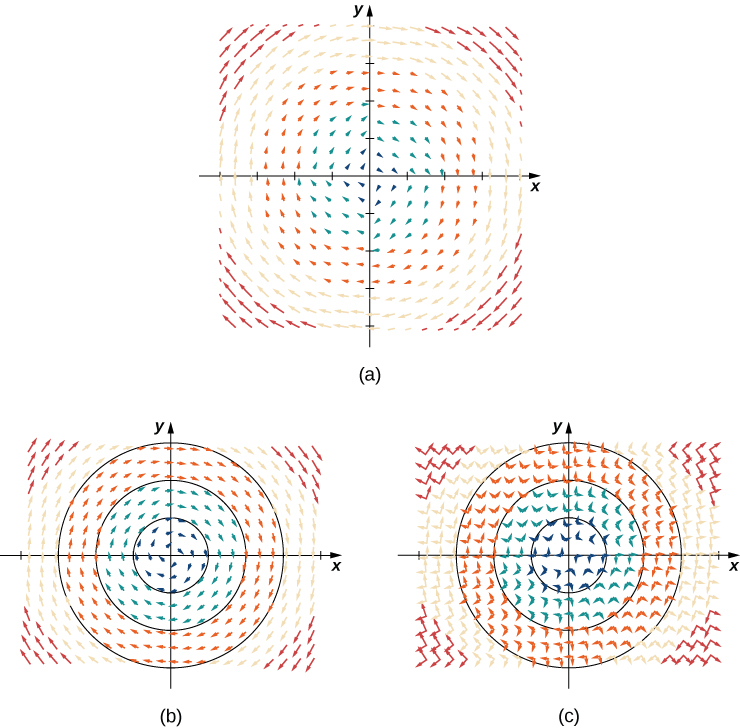

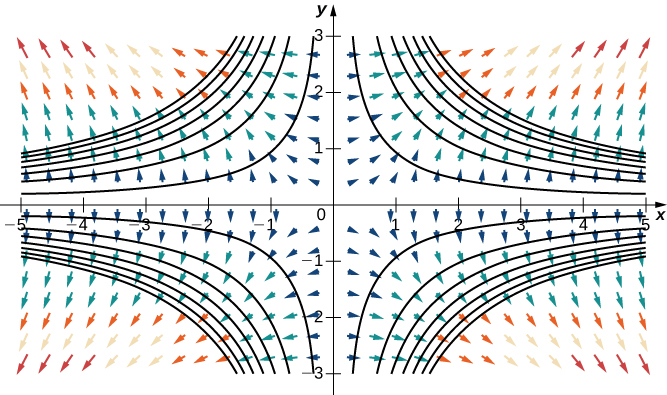

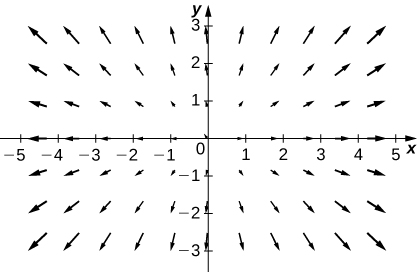

Sketch the vector field

To sketch this vector field, choose a sample of points from each quadrant and compute the corresponding vector. The following table gives a representative sample of points in a plane and the corresponding vectors.

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”}{: .unnumbered summary=”A table with six columns and five rows. The first row has the values (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), and F(x,y). The second row has the values (1,0), <1/2,0>, (2,0), <1,0>, (1,1), <1/2,1/2>. The third row has the values (0,1), <0,1/2>, (0,2), <0,1>, (-1,1), <-1/2,1/2>. The fourth row has the values (-1,0), <-1/2,0>, (-2,0), <-1,0>, (-1,-1), <-1/2,-1/2>. The fifth row has the values (0,-1), <0,-1/2>, (0,-2), <0,-1>, (1,-1), <1/2,-1/2>.” data-label=””}

[link](a) shows the vector field. To see that each vector is perpendicular to the corresponding circle, [link](b) shows circles overlain on the vector field.

Draw the radial field

Sketch enough vectors to get an idea of the shape.

In contrast to radial fields, in a rotational field, the vector at point

is tangent (not perpendicular) to a circle with radius

In a standard rotational field, all vectors point either in a clockwise direction or in a counterclockwise direction, and the magnitude of a vector depends only on its distance from the origin. Both of the following examples are clockwise rotational fields, and we see from their visual representations that the vectors appear to rotate around the origin.

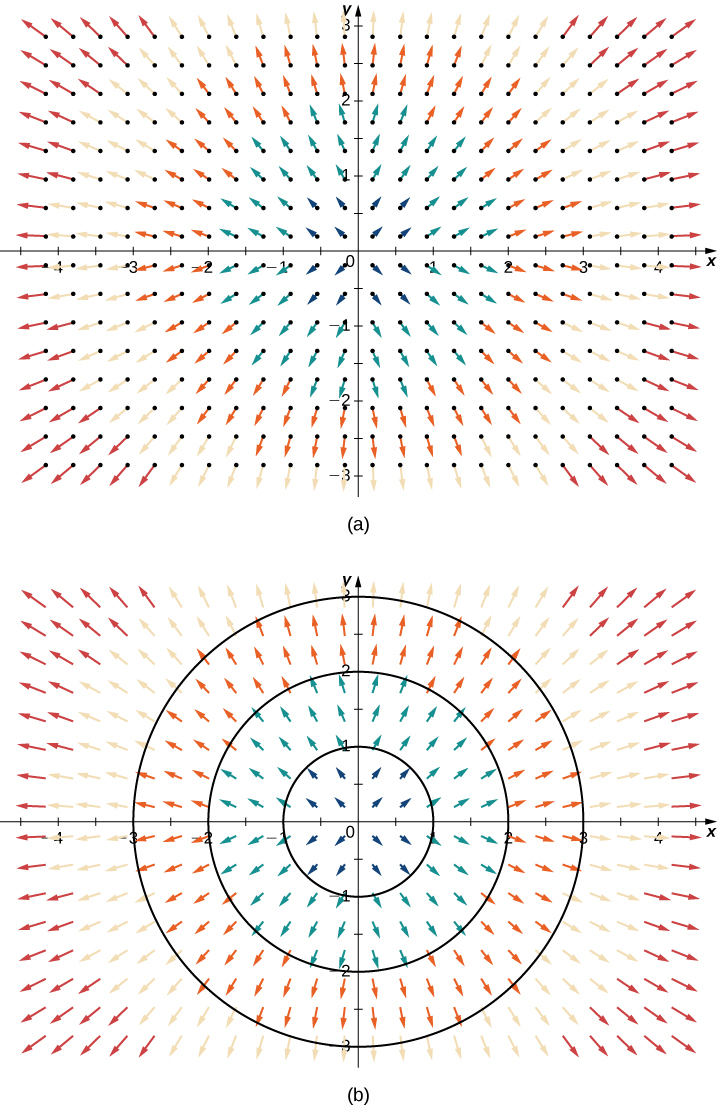

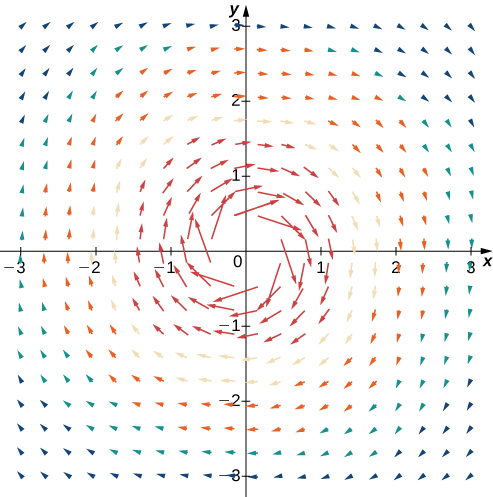

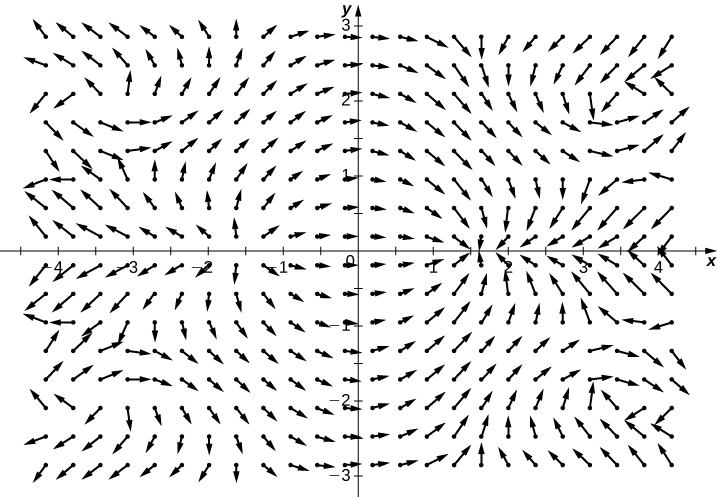

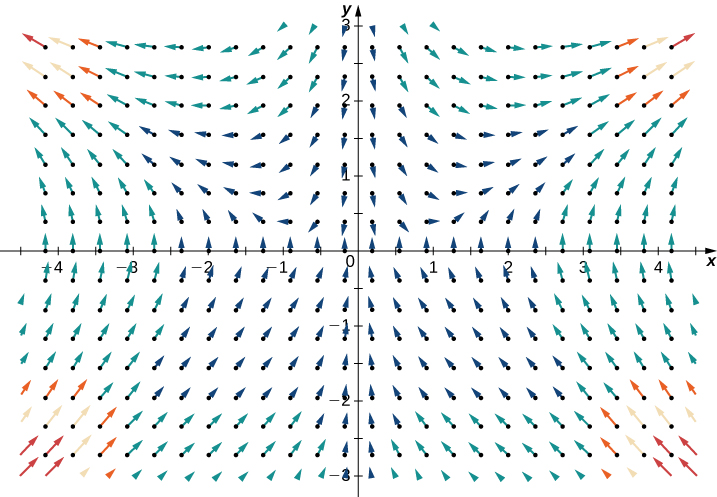

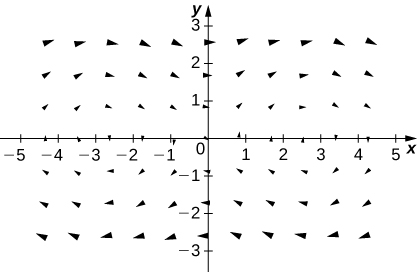

Sketch the vector field

Create a table (see the one that follows) using a representative sample of points in a plane and their corresponding vectors. [link] shows the resulting vector field.

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”}{: .unnumbered summary=”A table with six columns and five rows. The first row has the values (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), and F(x,y). The second row has the values (1,0), <0,-1>, (2,0), <0,-2>, (1,1), <1,-1>. The third row has the values (0,1), <1,0>, (0,2), <2,0>, (-1,1), <1,1>. The fourth row has the values (-1,0), <0,1>, (-2,0), <0,2>, (-1,-1), <-1,1>. The fifth row has the values (0,-1), <-1,0>, (0,-2), <-2,0>, (1,-1), <-1,-1>.” data-label=””}

Note that vector

points clockwise and is perpendicular to radial vector

(We can verify this assertion by computing the dot product of the two vectors:

Furthermore, vector

has length

Thus, we have a complete description of this rotational vector field: the vector associated with point

is the vector with length r tangent to the circle with radius r, and it points in the clockwise direction.

Sketches such as that in [link] are often used to analyze major storm systems, including hurricanes and cyclones. In the northern hemisphere, storms rotate counterclockwise; in the southern hemisphere, storms rotate clockwise. (This is an effect caused by Earth’s rotation about its axis and is called the Coriolis Effect.)

Sketch vector field

To visualize this vector field, first note that the dot product

is zero for any point

Therefore, each vector is tangent to the circle on which it is located. Also, as

the magnitude of

goes to infinity. To see this, note that

Since

as

then

as

This vector field looks similar to the vector field in [link], but in this case the magnitudes of the vectors close to the origin are large. [link] shows a sample of points and the corresponding vectors, and [link] shows the vector field. Note that this vector field models the whirlpool motion of the river in [link](b). The domain of this vector field is all of

except for point

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”}{: .unnumbered summary=”A table with six columns and five rows. The first row has the values (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), F(x,y), (x,y), and F(x,y). The second row has the values (1,0), <0,-1>, (2,0), <0,-1/2>, (1,1), <1/2, -1/2>. The third row has the values (0,1), <1,0>, (0,2), <1/2, 0>, (-1,1), <1/2,1/2>. The fourth row has the values (-1,0), <0,1>, (-2,0), <0,1/2>, (-1,-1), <-1/2,1/2>. The fifth row has the values (0,-1), <-1,0>, (0,-2), <-1/2,0>, (1,-1), <-1/2,-1/2>.” data-label=””}

Sketch vector field

Is the vector field radial, rotational, or neither?

Rotational* * *

Substitute enough points into F to get an idea of the shape.

Suppose that

is the velocity field of a fluid. How fast is the fluid moving at point

(Assume the units of speed are meters per second.)

To find the velocity of the fluid at point

substitute the point into v:

The speed of the fluid at

is the magnitude of this vector. Therefore, the speed is

m/sec.

Vector field

models the velocity of water on the surface of a river. What is the speed of the water at point

Use meters per second as the units.

m/sec

Remember, speed is the magnitude of velocity.

We have examined vector fields that contain vectors of various magnitudes, but just as we have unit vectors, we can also have a unit vector field. A vector field F is a unit vector field if the magnitude of each vector in the field is 1. In a unit vector field, the only relevant information is the direction of each vector.

Show that vector field

is a unit vector field.

To show that F is a unit field, we must show that the magnitude of each vector is 1. Note that

Therefore, F is a unit vector field.

Is vector field

a unit vector field?

No.

Calculate the magnitude of F at an arbitrary point

Why are unit vector fields important? Suppose we are studying the flow of a fluid, and we care only about the direction in which the fluid is flowing at a given point. In this case, the speed of the fluid (which is the magnitude of the corresponding velocity vector) is irrelevant, because all we care about is the direction of each vector. Therefore, the unit vector field associated with velocity is the field we would study.

If

is a vector field, then the corresponding unit vector field is

Notice that if

is the vector field from [link], then the magnitude of F is

and therefore the corresponding unit vector field is the field G from the previous example.

If F is a vector field, then the process of dividing F by its magnitude to form unit vector field

is called normalizing the field F.

We have seen several examples of vector fields in

let’s now turn our attention to vector fields in

These vector fields can be used to model gravitational or electromagnetic fields, and they can also be used to model fluid flow or heat flow in three dimensions. A two-dimensional vector field can really only model the movement of water on a two-dimensional slice of a river (such as the river’s surface). Since a river flows through three spatial dimensions, to model the flow of the entire depth of the river, we need a vector field in three dimensions.

The extra dimension of a three-dimensional field can make vector fields in

more difficult to visualize, but the idea is the same. To visualize a vector field in

plot enough vectors to show the overall shape. We can use a similar method to visualizing a vector field in

by choosing points in each octant.

Just as with vector fields in

we can represent vector fields in

with component functions. We simply need an extra component function for the extra dimension. We write either

or

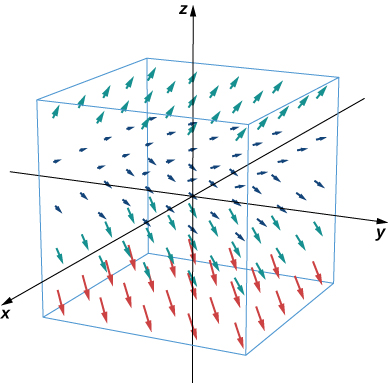

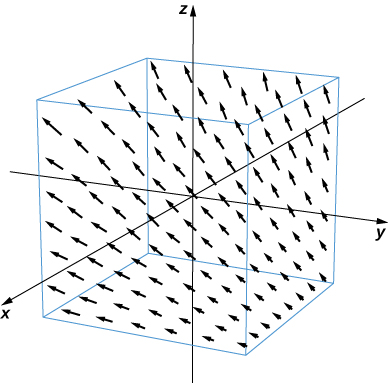

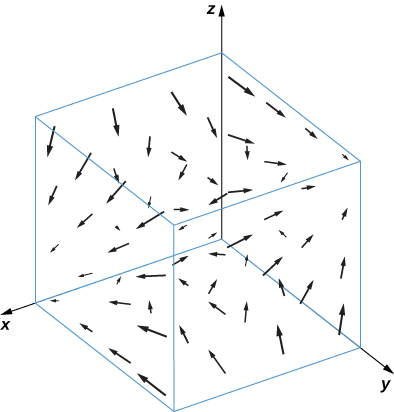

Describe vector field

For this vector field, the x and y components are constant, so every point in

has an associated vector with x and y components equal to one. To visualize F, we first consider what the field looks like in the xy-plane. In the xy-plane,

Hence, each point of the form

has vector

associated with it. For points not in the xy-plane but slightly above it, the associated vector has a small but positive z component, and therefore the associated vector points slightly upward. For points that are far above the xy-plane, the z component is large, so the vector is almost vertical. [link] shows this vector field.

Sketch vector field

Substitute enough points into the vector field to get an idea of the general shape.

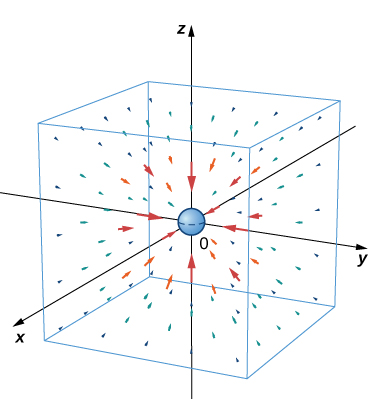

In the next example, we explore one of the classic cases of a three-dimensional vector field: a gravitational field.

Newton’s law of gravitation states that

where G is the universal gravitational constant. It describes the gravitational field exerted by an object (object 1) of mass

located at the origin on another object (object 2) of mass

located at point

Field F denotes the gravitational force that object 1 exerts on object 2, r is the distance between the two objects, and

indicates the unit vector from the first object to the second. The minus sign shows that the gravitational force attracts toward the origin; that is, the force of object 1 is attractive. Sketch the vector field associated with this equation.

Since object 1 is located at the origin, the distance between the objects is given by

The unit vector from object 1 to object 2 is

and hence

Therefore, gravitational vector field F exerted by object 1 on object 2 is

This is an example of a radial vector field in

[link] shows what this gravitational field looks like for a large mass at the origin. Note that the magnitudes of the vectors increase as the vectors get closer to the origin.

The mass of asteroid 1 is 750,000 kg and the mass of asteroid 2 is 130,000 kg. Assume asteroid 1 is located at the origin, and asteroid 2 is located at

measured in units of 10 to the eighth power kilometers. Given that the universal gravitational constant is

find the gravitational force vector that asteroid 1 exerts on asteroid 2.

Follow [link] and first compute the distance between the asteroids.

In this section, we study a special kind of vector field called a gradient field or a conservative field. These vector fields are extremely important in physics because they can be used to model physical systems in which energy is conserved. Gravitational fields and electric fields associated with a static charge are examples of gradient fields.

Recall that if

is a (scalar) function of x and y, then the gradient of

is

We can see from the form in which the gradient is written that

is a vector field in

Similarly, if

is a function of x, y, and z, then the gradient of

is

The gradient of a three-variable function is a vector field in

A gradient field is a vector field that can be written as the gradient of a function, and we have the following definition.

A vector field

in

or in

is a gradient field if there exists a scalar function

such that

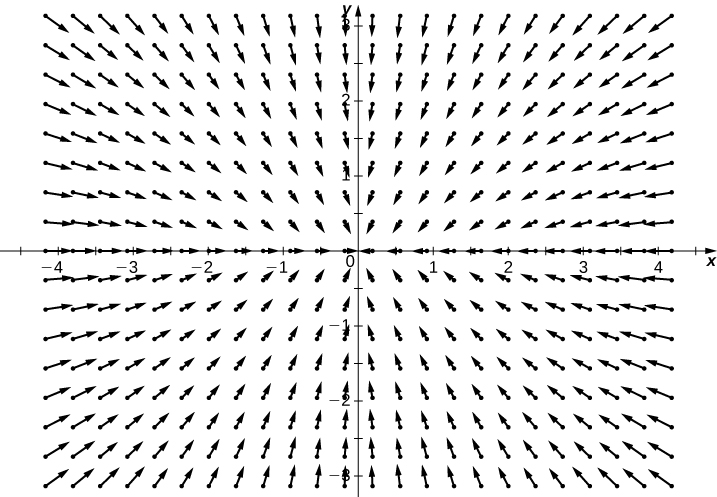

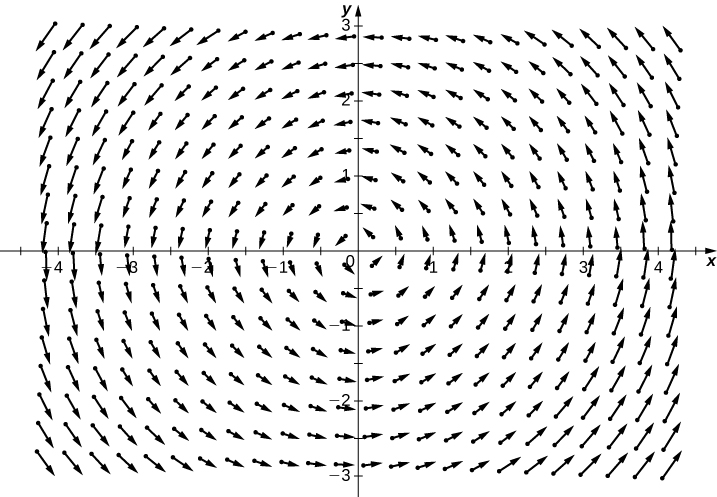

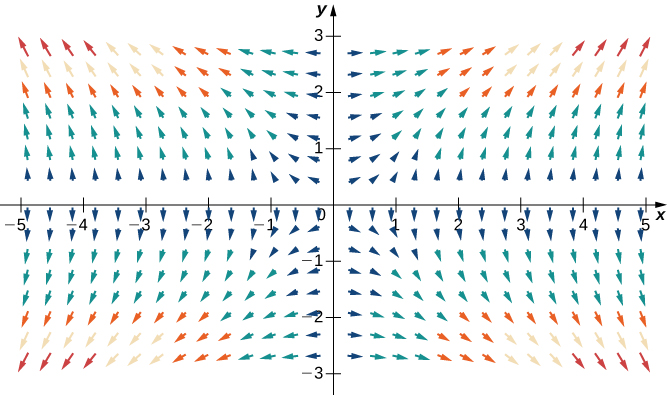

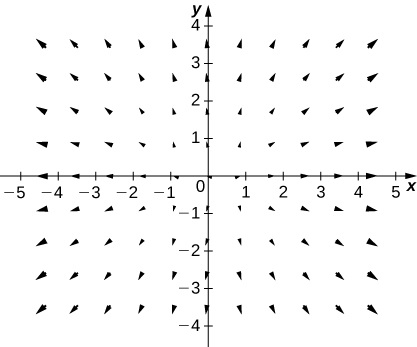

Use technology to plot the gradient vector field of

The gradient of

is

To sketch the vector field, use a computer algebra system such as Mathematica. [link] shows

Use technology to plot the gradient vector field of

Find the gradient of

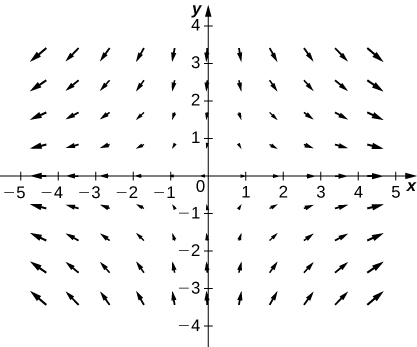

Consider the function

from [link]. [link] shows the level curves of this function overlaid on the function’s gradient vector field. The gradient vectors are perpendicular to the level curves, and the magnitudes of the vectors get larger as the level curves get closer together, because closely grouped level curves indicate the graph is steep, and the magnitude of the gradient vector is the largest value of the directional derivative. Therefore, you can see the local steepness of a graph by investigating the corresponding function’s gradient field.

As we learned earlier, a vector field

is a conservative vector field, or a gradient field if there exists a scalar function

such that

In this situation,

is called a potential function for

Conservative vector fields arise in many applications, particularly in physics. The reason such fields are called conservative is that they model forces of physical systems in which energy is conserved. We study conservative vector fields in more detail later in this chapter.

You might notice that, in some applications, a potential function

for F is defined instead as a function such that

This is the case for certain contexts in physics, for example.

Is

a potential function for vector field

We need to confirm whether

We have

Therefore,

and

is a potential function for

Is

a potential function for

No

Compute the gradient of

The velocity of a fluid is modeled by field

Verify that

is a potential function for v.

To show that

is a potential function, we must show that

Note that

and

Therefore,

and

is a potential function for v ([link]).

Verify that

is a potential function for velocity field

Calculate the gradient.

If F is a conservative vector field, then there is at least one potential function

such that

But, could there be more than one potential function? If so, is there any relationship between two potential functions for the same vector field? Before answering these questions, let’s recall some facts from single-variable calculus to guide our intuition. Recall that if

is an integrable function, then k has infinitely many antiderivatives. Furthermore, if F and G are both antiderivatives of k, then F and G differ only by a constant. That is, there is some number C such that

Now let F be a conservative vector field and let

and g be potential functions for F. Since the gradient is like a derivative, F being conservative means that F is “integrable” with “antiderivatives”

and g. Therefore, if the analogy with single-variable calculus is valid, we expect there is some constant C such that

The next theorem says that this is indeed the case.

To state the next theorem with precision, we need to assume the domain of the vector field is connected and open. To be connected means if

and

are any two points in the domain, then you can walk from

to

along a path that stays entirely inside the domain.

Let F be a conservative vector field on an open and connected domain and let

and g be functions such that

and

Then, there is a constant C such that

Since

and g are both potential functions for F, then

Let

then we have

We would like to show that h is a constant function.

Assume h is a function of x and y (the logic of this proof extends to any number of independent variables). Since

we have

and

The expression

implies that h is a constant function with respect to x—that is,

for some function k1. Similarly,

implies

for some function k2. Therefore, function h depends only on y and also depends only on x. Thus,

for some constant C on the connected domain of F. Note that we really do need connectedness at this point; if the domain of F came in two separate pieces, then k could be a constant C1 on one piece but could be a different constant C2 on the other piece. Since

we have that

as desired.

□

Conservative vector fields also have a special property called the cross-partial property. This property helps test whether a given vector field is conservative.

Let F be a vector field in two or three dimensions such that the component functions of F have continuous second-order mixed-partial derivatives on the domain of F.

If

is a conservative vector field in

then

If

is a conservative vector field in

then

Since F is conservative, there is a function

such that

Therefore, by the definition of the gradient,

and

By Clairaut’s theorem,

But,

and

and thus

□

Clairaut’s theorem gives a fast proof of the cross-partial property of conservative vector fields in

just as it did for vector fields in

[link] shows that most vector fields are not conservative. The cross-partial property is difficult to satisfy in general, so most vector fields won’t have equal cross-partials.

Show that rotational vector field

is not conservative.

Let

If F is conservative, then the cross-partials would be equal—that is,

would equal

Therefore, to show that F is not conservative, check that

Since

and

the vector field is not conservative.

Show that vector field

is not conservative.

Check the cross-partials.

Is vector field

conservative?

Let

and

If F is conservative, then all three cross-partial equations will be satisfied—that is, if F is conservative, then

would equal

would equal

and

would equal

Note that

so the first two necessary equalities hold. However,

and

so

Therefore,

is not conservative.

Is vector field

conservative?

No

Check the cross-partials.

We conclude this section with a word of warning: [link] says that if F is conservative, then F has the cross-partial property. The theorem does not say that, if F has the cross-partial property, then F is conservative (the converse of an implication is not logically equivalent to the original implication). In other words, [link] can only help determine that a field is not conservative; it does not let you conclude that a vector field is conservative. For example, consider vector field

This field has the cross-partial property, so it is natural to try to use [link] to conclude this vector field is conservative. However, this is a misapplication of the theorem. We learn later how to conclude that F is conservative.

to each point

in a subset D of

to each point

in a subset D of

is called conservative if there exists a scalar function

such that

**Vector field in

**

or

**Vector field in

**

or

The domain of vector field

is a set of points

in a plane, and the range of F is a set of what in the plane?

Vectors

For the following exercises, determine whether the statement is true or false.

Vector field

is a gradient field for both

and

Vector field

is constant in direction and magnitude on a unit circle.

False

Vector field

is neither a radial field nor a rotation.

For the following exercises, describe each vector field by drawing some of its vectors.

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

[T]

For the following exercises, find the gradient vector field of each function

What is vector field

with a value at

that is of unit length and points toward

For the following exercises, write formulas for the vector fields with the given properties.

All vectors are parallel to the x-axis and all vectors on a vertical line have the same magnitude.

All vectors point toward the origin and have constant length.

All vectors are of unit length and are perpendicular to the position vector at that point.

Give a formula

for the vector field in a plane that has the properties that

at

and that at any other point

F is tangent to circle

and points in the clockwise direction with magnitude

Is vector field

a gradient field?

Find a formula for vector field

given the fact that for all points

F points toward the origin and

For the following exercises, assume that an electric field in the xy-plane caused by an infinite line of charge along the x-axis is a gradient field with potential function

where

is a constant and

is a reference distance at which the potential is assumed to be zero.

Find the components of the electric field in the x- and y-directions, where

Show that the electric field at a point in the xy-plane is directed outward from the origin and has magnitude

where

A flow line (or streamline) of a vector field

is a curve

such that

If

represents the velocity field of a moving particle, then the flow lines are paths taken by the particle. Therefore, flow lines are tangent to the vector field. For the following exercises, show that the given curve

is a flow line of the given velocity vector field

For the following exercises, let

and

Match F, G, and H with their graphs.

H

For the following exercises, let

and

Match the vector fields with their graphs in

d.

a.

such that

for which there exists a scalar function

such that

in other words, a vector field that is the gradient of a function; such vector fields are also called conservative

such that

is tangent to a circle with radius

in a rotational field, all vectors flow either clockwise or counterclockwise, and the magnitude of a vector depends only on its distance from the origin

an assignment of a vector

to each point

of a subset

of

in

an assignment of a vector

to each point

of a subset

of

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: