If we apply a force to an object so that the object moves, we say that work is done by the force. In Introduction to Applications of Integration on integration applications, we looked at a constant force and we assumed the force was applied in the direction of motion of the object. Under those conditions, work can be expressed as the product of the force acting on an object and the distance the object moves. In this chapter, however, we have seen that both force and the motion of an object can be represented by vectors.

In this section, we develop an operation called the dot product, which allows us to calculate work in the case when the force vector and the motion vector have different directions. The dot product essentially tells us how much of the force vector is applied in the direction of the motion vector. The dot product can also help us measure the angle formed by a pair of vectors and the position of a vector relative to the coordinate axes. It even provides a simple test to determine whether two vectors meet at a right angle.

We have already learned how to add and subtract vectors. In this chapter, we investigate two types of vector multiplication. The first type of vector multiplication is called the dot product, based on the notation we use for it, and it is defined as follows:

The dot product of vectors

and

is given by the sum of the products of the components

Note that if u and v are two-dimensional vectors, we calculate the dot product in a similar fashion. Thus, if

and

then

When two vectors are combined under addition or subtraction, the result is a vector. When two vectors are combined using the dot product, the result is a scalar. For this reason, the dot product is often called the scalar product. It may also be called the inner product.

and

and

Find

where

and

7

Multiply corresponding components and then add their products.

Like vector addition and subtraction, the dot product has several algebraic properties. We prove three of these properties and leave the rest as exercises.

Let

and

be vectors, and let c be a scalar.

Let

and

Then

The associative property looks like the associative property for real-number multiplication, but pay close attention to the difference between scalar and vector objects:

The proof that

is similar.

The fourth property shows the relationship between the magnitude of a vector and its dot product with itself:

□

Note that the definition of the dot product yields

By property iv., if

then

Let

and

Find each of the following products.

Find the following products for

and

a.

b.

is a scalar.

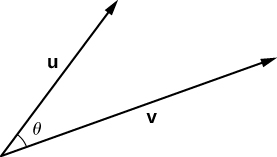

When two nonzero vectors are placed in standard position, whether in two dimensions or three dimensions, they form an angle between them ([link]). The dot product provides a way to find the measure of this angle. This property is a result of the fact that we can express the dot product in terms of the cosine of the angle formed by two vectors.

The dot product of two vectors is the product of the magnitude of each vector and the cosine of the angle between them:

Place vectors u and v in standard position and consider the vector

([link]). These three vectors form a triangle with side lengths

Recall from trigonometry that the law of cosines describes the relationship among the side lengths of the triangle and the angle θ. Applying the law of cosines here gives

The dot product provides a way to rewrite the left side of this equation:

Substituting into the law of cosines yields

□

We can use this form of the dot product to find the measure of the angle between two nonzero vectors. The following equation rearranges [link] to solve for the cosine of the angle:

Using this equation, we can find the cosine of the angle between two nonzero vectors. Since we are considering the smallest angle between the vectors, we assume

(or

if we are working in radians). The inverse cosine is unique over this range, so we are then able to determine the measure of the angle

Find the measure of the angle between each pair of vectors.

and

Therefore,

rad.

Now,

and

so

Find the measure of the angle, in radians, formed by vectors

and

Round to the nearest hundredth.

rad

Use the equation

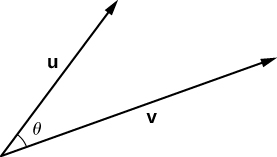

The angle between two vectors can be acute

obtuse

or straight

If

then both vectors have the same direction. If

then the vectors, when placed in standard position, form a right angle ([link]). We can formalize this result into a theorem regarding orthogonal (perpendicular) vectors.

The nonzero vectors u and v are orthogonal vectors if and only if

Let u and v be nonzero vectors, and let

denote the angle between them. First, assume

Then

However,

and

so we must have

Hence,

and the vectors are orthogonal.

Now assume u and v are orthogonal. Then

and we have

□

The terms orthogonal, perpendicular, and normal each indicate that mathematical objects are intersecting at right angles. The use of each term is determined mainly by its context. We say that vectors are orthogonal and lines are perpendicular. The term normal is used most often when measuring the angle made with a plane or other surface.

Determine whether

and

are orthogonal vectors.

Using the definition, we need only check the dot product of the vectors:

Because

the vectors are orthogonal ([link]).

For which value of x is

orthogonal to

Vectors p and q are orthogonal if and only if

Let

Find the measures of the angles formed by the following vectors.

Let

Find the measure of the angles formed by each pair of vectors.

a.

rad; b.

rad; c.

rad

and

The angle a vector makes with each of the coordinate axes, called a direction angle, is very important in practical computations, especially in a field such as engineering. For example, in astronautical engineering, the angle at which a rocket is launched must be determined very precisely. A very small error in the angle can lead to the rocket going hundreds of miles off course. Direction angles are often calculated by using the dot product and the cosines of the angles, called the direction cosines. Therefore, we define both these angles and their cosines.

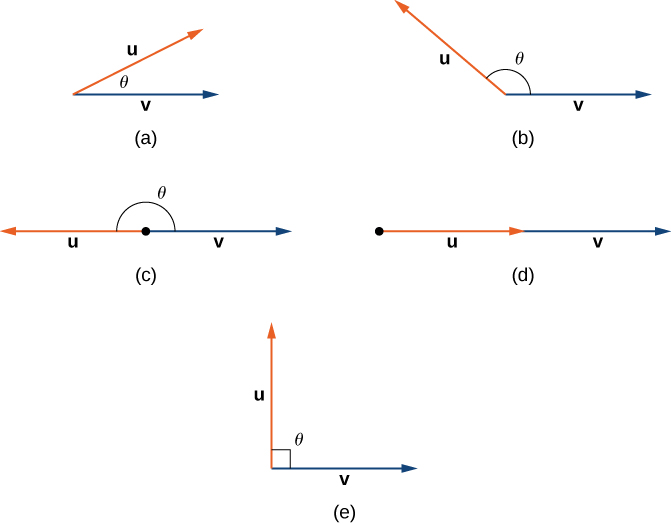

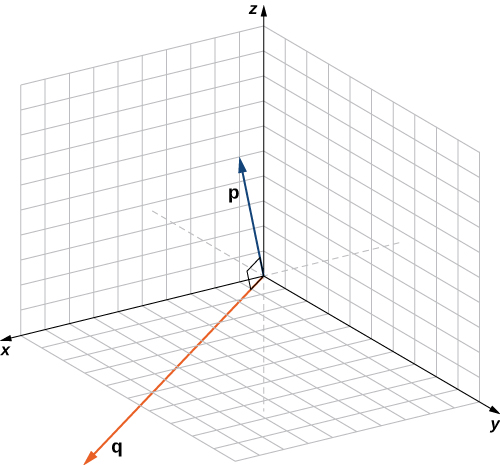

The angles formed by a nonzero vector and the coordinate axes are called the direction angles for the vector ([link]). The cosines for these angles are called the direction cosines.

In [link], the direction cosines of

are

and

The direction angles of v are

and

So far, we have focused mainly on vectors related to force, movement, and position in three-dimensional physical space. However, vectors are often used in more abstract ways. For example, suppose a fruit vendor sells apples, bananas, and oranges. On a given day, he sells 30 apples, 12 bananas, and 18 oranges. He might use a quantity vector,

to represent the quantity of fruit he sold that day. Similarly, he might want to use a price vector,

to indicate that he sells his apples for 50¢ each, bananas for 25¢ each, and oranges for $1 apiece. In this example, although we could still graph these vectors, we do not interpret them as literal representations of position in the physical world. We are simply using vectors to keep track of particular pieces of information about apples, bananas, and oranges.

This idea might seem a little strange, but if we simply regard vectors as a way to order and store data, we find they can be quite a powerful tool. Going back to the fruit vendor, let’s think about the dot product,

We compute it by multiplying the number of apples sold (30) by the price per apple (50¢), the number of bananas sold by the price per banana, and the number of oranges sold by the price per orange. We then add all these values together. So, in this example, the dot product tells us how much money the fruit vendor had in sales on that particular day.

When we use vectors in this more general way, there is no reason to limit the number of components to three. What if the fruit vendor decides to start selling grapefruit? In that case, he would want to use four-dimensional quantity and price vectors to represent the number of apples, bananas, oranges, and grapefruit sold, and their unit prices. As you might expect, to calculate the dot product of four-dimensional vectors, we simply add the products of the components as before, but the sum has four terms instead of three.

AAA Party Supply Store sells invitations, party favors, decorations, and food service items such as paper plates and napkins. When AAA buys its inventory, it pays 25¢ per package for invitations and party favors. Decorations cost AAA 50¢ each, and food service items cost 20¢ per package. AAA sells invitations for $2.50 per package and party favors for $1.50 per package. Decorations sell for $4.50 each and food service items for $1.25 per package.

During the month of May, AAA Party Supply Store sells 1258 invitations, 342 party favors, 2426 decorations, and 1354 food service items. Use vectors and dot products to calculate how much money AAA made in sales during the month of May. How much did the store make in profit?

The cost, price, and quantity vectors are

AAA sales for the month of May can be calculated using the dot product

We have

So, AAA took in $16,267.50 during the month of May.

To calculate the profit, we must first calculate how much AAA paid for the items sold. We use the dot product

to get

So, AAA paid $1,883.30 for the items they sold. Their profit, then, is given by

Therefore, AAA Party Supply Store made $14,383.70 in May.

On June 1, AAA Party Supply Store decided to increase the price they charge for party favors to $2 per package. They also changed suppliers for their invitations, and are now able to purchase invitations for only 10¢ per package. All their other costs and prices remain the same. If AAA sells 1408 invitations, 147 party favors, 2112 decorations, and 1894 food service items in the month of June, use vectors and dot products to calculate their total sales and profit for June.

Sales = $15,685.50; profit = $14,073.15

Use four-dimensional vectors for cost, price, and quantity sold.

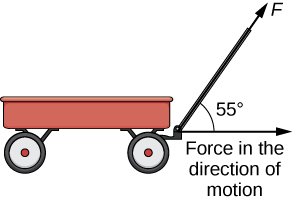

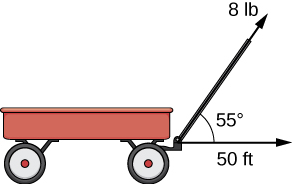

As we have seen, addition combines two vectors to create a resultant vector. But what if we are given a vector and we need to find its component parts? We use vector projections to perform the opposite process; they can break down a vector into its components. The magnitude of a vector projection is a scalar projection. For example, if a child is pulling the handle of a wagon at a 55° angle, we can use projections to determine how much of the force on the handle is actually moving the wagon forward ([link]). We return to this example and learn how to solve it after we see how to calculate projections.

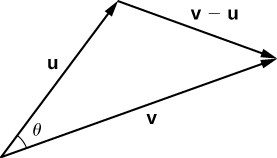

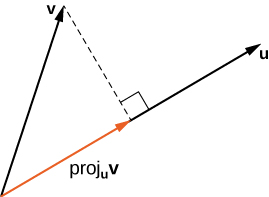

The vector projection of v onto u is the vector labeled projuv in [link]. It has the same initial point as u and v and the same direction as u, and represents the component of v that acts in the direction of u. If

represents the angle between u and v, then, by properties of triangles, we know the length of

is

When expressing

in terms of the dot product, this becomes

We now multiply by a unit vector in the direction of u to get

The length of this vector is also known as the scalar projection of v onto u and is denoted by

Find the projection of v onto u.

and

and

Sometimes it is useful to decompose vectors—that is, to break a vector apart into a sum. This process is called the resolution of a vector into components. Projections allow us to identify two orthogonal vectors having a desired sum. For example, let

and let

We want to decompose the vector v into orthogonal components such that one of the component vectors has the same direction as u.

We first find the component that has the same direction as u by projecting v onto u. Let

Then, we have

Now consider the vector

We have

Clearly, by the way we defined q, we have

and

Therefore, q and p are orthogonal.

Express

as a sum of orthogonal vectors such that one of the vectors has the same direction as

Let p represent the projection of v onto u:

Then,

To check our work, we can use the dot product to verify that p and q are orthogonal vectors:

Then,

Express

as a sum of orthogonal vectors such that one of the vectors has the same direction as

where

and

Start by finding the projection of v onto u.

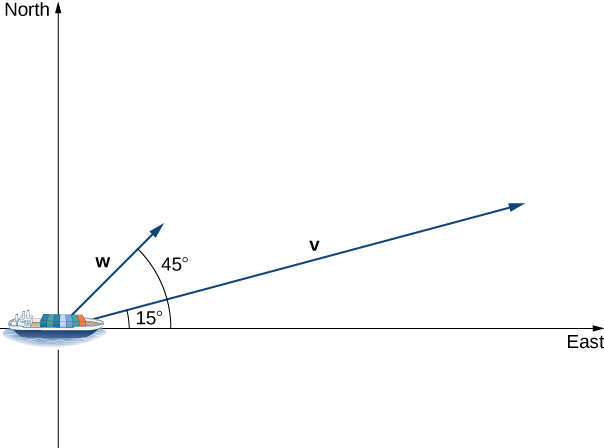

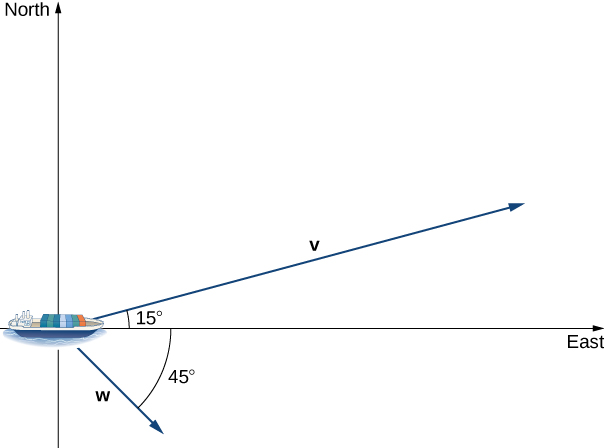

A container ship leaves port traveling

north of east. Its engine generates a speed of 20 knots along that path (see the following figure). In addition, the ocean current moves the ship northeast at a speed of 2 knots. Considering both the engine and the current, how fast is the ship moving in the direction

north of east? Round the answer to two decimal places.

Let v be the velocity vector generated by the engine, and let w be the velocity vector of the current. We already know

along the desired route. We just need to add in the scalar projection of w onto v. We get

The ship is moving at 21.73 knots in the direction

north of east.

Repeat the previous example, but assume the ocean current is moving southeast instead of northeast, as shown in the following figure.

21 knots

Compute the scalar projection of w onto v.

Now that we understand dot products, we can see how to apply them to real-life situations. The most common application of the dot product of two vectors is in the calculation of work.

From physics, we know that work is done when an object is moved by a force. When the force is constant and applied in the same direction the object moves, then we define the work done as the product of the force and the distance the object travels:

We saw several examples of this type in earlier chapters. Now imagine the direction of the force is different from the direction of motion, as with the example of a child pulling a wagon. To find the work done, we need to multiply the component of the force that acts in the direction of the motion by the magnitude of the displacement. The dot product allows us to do just that. If we represent an applied force by a vector F and the displacement of an object by a vector s, then the work done by the force is the dot product of F and s.

When a constant force is applied to an object so the object moves in a straight line from point P to point Q, the work W done by the force F, acting at an angle θ from the line of motion, is given by

Let’s revisit the problem of the child’s wagon introduced earlier. Suppose a child is pulling a wagon with a force having a magnitude of 8 lb on the handle at an angle of 55°. If the child pulls the wagon 50 ft, find the work done by the force ([link]).

We have

In U.S. standard units, we measure the magnitude of force

in pounds. The magnitude of the displacement vector

tells us how far the object moved, and it is measured in feet. The customary unit of measure for work, then, is the foot-pound. One foot-pound is the amount of work required to move an object weighing 1 lb a distance of 1 ft straight up. In the metric system, the unit of measure for force is the newton (N), and the unit of measure of magnitude for work is a newton-meter (N·m), or a joule (J).

A conveyor belt generates a force

that moves a suitcase from point

to point

along a straight line. Find the work done by the conveyor belt. The distance is measured in meters and the force is measured in newtons.

The displacement vector

has initial point

and terminal point

Work is the dot product of force and displacement:

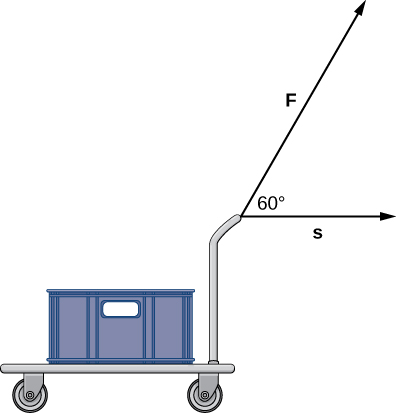

A constant force of 30 lb is applied at an angle of 60° to pull a handcart 10 ft across the ground ([link]). What is the work done by this force?

150 ft-lb

Use the definition of work as the dot product of force and distance.

and

is

This form of the dot product is useful for finding the measure of the angle formed by two vectors.

The magnitude of this vector is known as the scalar projection of v onto u, given by

For the following exercises, the vectors u and v are given. Calculate the dot product

6

0

For the following exercises, the vectors a, b, and c are given. Determine the vectors

and

Express the vectors in component form.

For the following exercises, the two-dimensional vectors a and b are given.

between a and b. Express the answer in radians rounded to two decimal places, if it is not possible to express it exactly.

an acute angle?

[T]

a.

rad; b.

is not acute.

[T]

a.

rad; b.

is acute.

For the following exercises, find the measure of the angle between the three-dimensional vectors a and b. Express the answer in radians rounded to two decimal places, if it is not possible to express it exactly.

[T]

where

and

rad

[T]

where

and

For the following exercises determine whether the given vectors are orthogonal.

where x and y are nonzero real numbers

Orthogonal

where x and y are nonzero real numbers

Not orthogonal

Find all two-dimensional vectors a orthogonal to vector

Express the answer in component form.

where

is a real number

Find all two-dimensional vectors a orthogonal to vector

Express the answer by using standard unit vectors.

Determine all three-dimensional vectors u orthogonal to vector

Express the answer by using standard unit vectors.

where

and

are real numbers such that

Determine all three-dimensional vectors u orthogonal to vector

Express the answer in component form.

Determine the real number

such that vectors

and

are orthogonal.

Determine the real number

such that vectors

and

are orthogonal.

[T] Consider the points

and

and

Express the answer by using standard unit vectors.

a.

b.

[T] Consider points

and

and

Express the answer in component form.

Determine the measure of angle A in triangle ABC, where

and

Express your answer in degrees rounded to two decimal places.

Consider points

and

Determine the angle between vectors

and

Express the answer in degrees rounded to two decimal places.

For the following exercises, determine which (if any) pairs of the following vectors are orthogonal.

u and v are orthogonal; v and w are orthogonal.

Use vectors to show that a parallelogram with equal diagonals is a square.

Use vectors to show that the diagonals of a rhombus are perpendicular.

Show that

is true for any vectors u, v, and w.

Verify the identity

for vectors

and

For the following problems, the vector u is given.

a.

and

b.

and

a.

and

b.

and

Consider

a nonzero three-dimensional vector. Let

and

be the directions of the cosines of u. Show that

Determine the direction cosines of vector

and show they satisfy

For the following exercises, the vectors u and v are given.

of vector v onto vector u. Express your answer in component form.

of vector v onto vector u.

a.

b.

a.

b.

Consider the vectors

and

that represents the projection of v onto u.

of vector v into the orthogonal components w and q, where w is the projection of v onto u and q is a vector orthogonal to the direction of u.

a.

b.

Consider vectors

and

that represents the projection of v onto u.

of vector v into the orthogonal components w and q, where w is the projection of v onto u and q is a vector orthogonal to the direction of u.

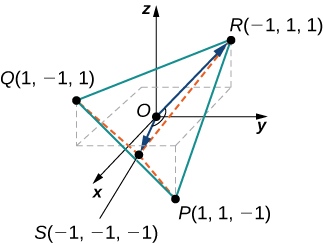

A methane molecule has a carbon atom situated at the origin and four hydrogen atoms located at points

(see figure).

and

that connect the carbon atom with the hydrogen atoms located at S and R, which is also called the bond angle. Express the answer in degrees rounded to two decimal places.

a.

b.

[T] Find the vectors that join the center of a clock to the hours 1:00, 2:00, and 3:00. Assume the clock is circular with a radius of 1 unit.

Find the work done by force

(measured in Newtons) that moves a particle from point

to point

along a straight line (the distance is measured in meters).

[T] A sled is pulled by exerting a force of 100 N on a rope that makes an angle of

with the horizontal. Find the work done in pulling the sled 40 m. (Round the answer to one decimal place.)

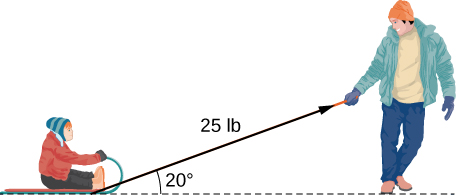

[T] A father is pulling his son on a sled at an angle of

with the horizontal with a force of 25 lb (see the following image). He pulls the sled in a straight path of 50 ft. How much work was done by the man pulling the sled? (Round the answer to the nearest integer.)

1175

[T] A car is towed using a force of 1600 N. The rope used to pull the car makes an angle of 25° with the horizontal. Find the work done in towing the car 2 km. Express the answer in joules

rounded to the nearest integer.

[T] A boat sails north aided by a wind blowing in a direction of

with a magnitude of 500 lb. How much work is performed by the wind as the boat moves 100 ft? (Round the answer to two decimal places.)

4330.13

Vector

represents the price of certain models of bicycles sold by a bicycle shop. Vector

represents the number of bicycles sold of each model, respectively. Compute the dot product

and state its meaning.

[T] Two forces

and

are represented by vectors with initial points that are at the origin. The first force has a magnitude of 20 lb and the terminal point of the vector is point

The second force has a magnitude of 40 lb and the terminal point of its vector is point

Let F be the resultant force of forces

and

a.

lb; b. The direction angles are

and

[T] Consider

the position vector of a particle at time

where the components of r are expressed in centimeters and time in seconds. Let

be the position vector of the particle after 1 sec.

where

is an arbitrary point, orthogonal to the instantaneous velocity vector

of the particle after 1 sec, can be expressed as

where

The set of point Q describes a plane called the normal plane to the path of the particle at point P.

where

and

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: