When describing the movement of an airplane in flight, it is important to communicate two pieces of information: the direction in which the plane is traveling and the plane’s speed. When measuring a force, such as the thrust of the plane’s engines, it is important to describe not only the strength of that force, but also the direction in which it is applied. Some quantities, such as or force, are defined in terms of both size (also called magnitude) and direction. A quantity that has magnitude and direction is called a vector. In this text, we denote vectors by boldface letters, such as v.

A vector is a quantity that has both magnitude and direction.

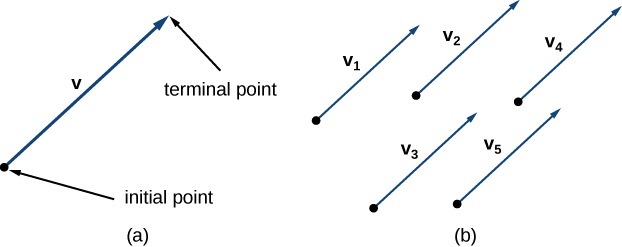

A vector in a plane is represented by a directed line segment (an arrow). The endpoints of the segment are called the initial point and the terminal point of the vector. An arrow from the initial point to the terminal point indicates the direction of the vector. The length of the line segment represents its magnitude. We use the notation

to denote the magnitude of the vector

A vector with an initial point and terminal point that are the same is called the zero vector, denoted

The zero vector is the only vector without a direction, and by convention can be considered to have any direction convenient to the problem at hand.

Vectors with the same magnitude and direction are called equivalent vectors. We treat equivalent vectors as equal, even if they have different initial points. Thus, if

and

are equivalent, we write

Vectors are said to be equivalent vectors if they have the same magnitude and direction.

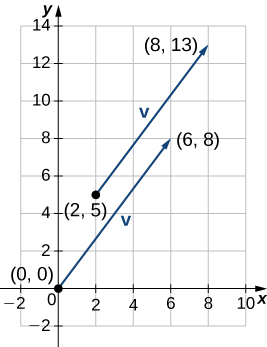

The arrows in [link](b) are equivalent. Each arrow has the same length and direction. A closely related concept is the idea of parallel vectors. Two vectors are said to be parallel if they have the same or opposite directions. We explore this idea in more detail later in the chapter. A vector is defined by its magnitude and direction, regardless of where its initial point is located.

The use of boldface, lowercase letters to name vectors is a common representation in print, but there are alternative notations. When writing the name of a vector by hand, for example, it is easier to sketch an arrow over the variable than to simulate boldface type:

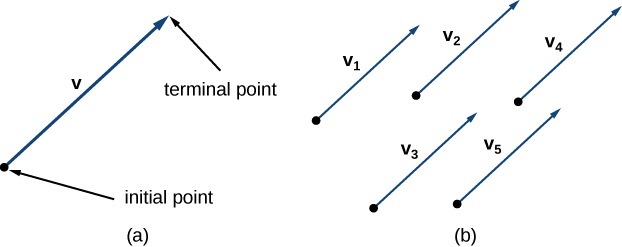

When a vector has initial point

and terminal point

the notation

is useful because it indicates the direction and location of the vector.

Sketch a vector in the plane from initial point

to terminal point

Sketch the vector

where

is point

and

is point

The first point listed in the name of the vector is the initial point of the vector.

Vectors have many real-life applications, including situations involving force or velocity. For example, consider the forces acting on a boat crossing a river. The boat’s motor generates a force in one direction, and the current of the river generates a force in another direction. Both forces are vectors. We must take both the magnitude and direction of each force into account if we want to know where the boat will go.

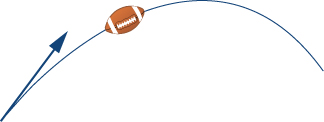

A second example that involves vectors is a quarterback throwing a football. The quarterback does not throw the ball parallel to the ground; instead, he aims up into the air. The velocity of his throw can be represented by a vector. If we know how hard he throws the ball (magnitude—in this case, speed), and the angle (direction), we can tell how far the ball will travel down the field.

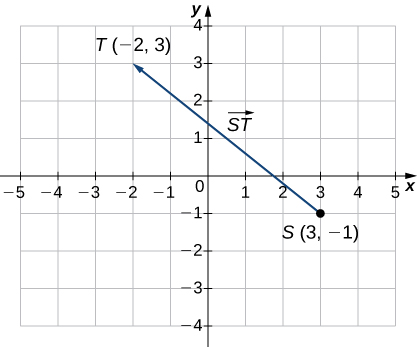

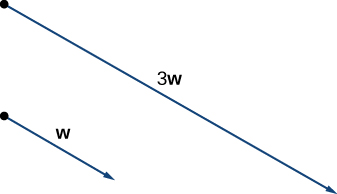

A real number is often called a scalar in mathematics and physics. Unlike vectors, scalars are generally considered to have a magnitude only, but no direction. Multiplying a vector by a scalar changes the vector’s magnitude. This is called scalar multiplication. Note that changing the magnitude of a vector does not indicate a change in its direction. For example, wind blowing from north to south might increase or decrease in speed while maintaining its direction from north to south.

The product

of a vector v and a scalar k is a vector with a magnitude that is

times the magnitude of

and with a direction that is the same as the direction of

if

and opposite the direction of

if

This is called scalar multiplication. If

or

then

As you might expect, if

we denote the product

as

Note that

has the same magnitude as

but has the opposite direction ([link]).

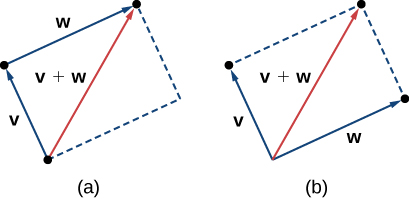

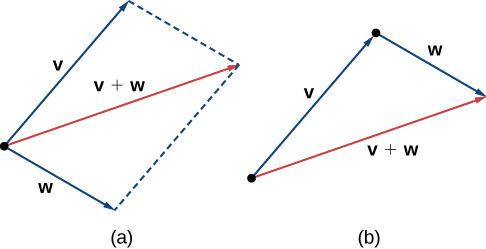

Another operation we can perform on vectors is to add them together in vector addition, but because each vector may have its own direction, the process is different from adding two numbers. The most common graphical method for adding two vectors is to place the initial point of the second vector at the terminal point of the first, as in [link](a). To see why this makes sense, suppose, for example, that both vectors represent displacement. If an object moves first from the initial point to the terminal point of vector

then from the initial point to the terminal point of vector

the overall displacement is the same as if the object had made just one movement from the initial point to the terminal point of the vector

For obvious reasons, this approach is called the triangle method. Notice that if we had switched the order, so that

was our first vector and v was our second vector, we would have ended up in the same place. (Again, see [link](a).) Thus,

A second method for adding vectors is called the parallelogram method. With this method, we place the two vectors so they have the same initial point, and then we draw a parallelogram with the vectors as two adjacent sides, as in [link](b). The length of the diagonal of the parallelogram is the sum. Comparing [link](b) and [link](a), we can see that we get the same answer using either method. The vector

is called the vector sum.

The sum of two vectors

and

can be constructed graphically by placing the initial point of

at the terminal point of

Then, the vector sum,

is the vector with an initial point that coincides with the initial point of

and has a terminal point that coincides with the terminal point of

This operation is known as vector addition.

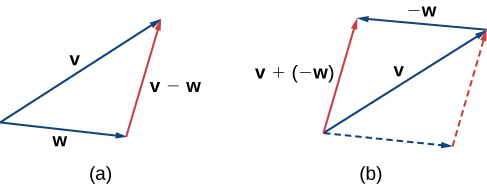

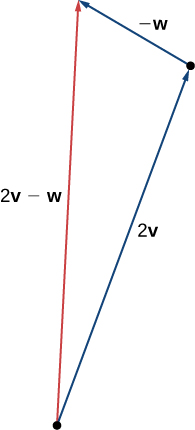

It is also appropriate here to discuss vector subtraction. We define

as

The vector

is called the vector difference. Graphically, the vector

is depicted by drawing a vector from the terminal point of

to the terminal point of

([link]).

In [link](a), the initial point of

is the initial point of

The terminal point of

is the terminal point of

These three vectors form the sides of a triangle. It follows that the length of any one side is less than the sum of the lengths of the remaining sides. So we have

This is known more generally as the triangle inequality. There is one case, however, when the resultant vector

has the same magnitude as the sum of the magnitudes of

and

This happens only when

and

have the same direction.

has the same direction as

it is three times as long as

Vector

has the same direction as

and is three times as long.

we can first rewrite the expression as

Then we can draw the vector

then add it to the vector

Working with vectors in a plane is easier when we are working in a coordinate system. When the initial points and terminal points of vectors are given in Cartesian coordinates, computations become straightforward.

Are

and

equivalent vectors?

has initial point

and terminal point

has initial point

and terminal point

has initial point

and terminal point

has initial point

and terminal point

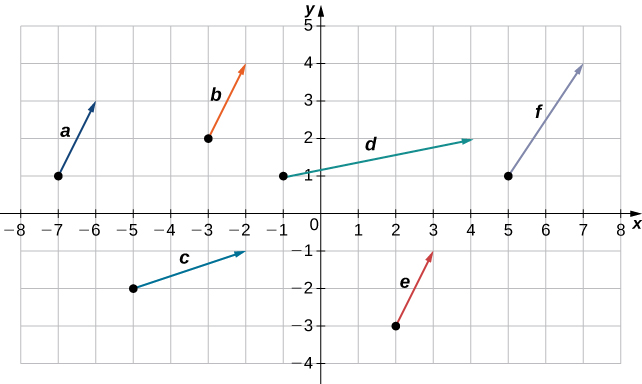

Which of the following vectors are equivalent?

Vectors

and

are equivalent.

Equivalent vectors have both the same magnitude and the same direction.

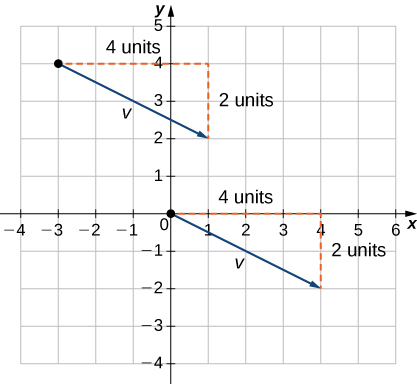

We have seen how to plot a vector when we are given an initial point and a terminal point. However, because a vector can be placed anywhere in a plane, it may be easier to perform calculations with a vector when its initial point coincides with the origin. We call a vector with its initial point at the origin a standard-position vector. Because the initial point of any vector in standard position is known to be

we can describe the vector by looking at the coordinates of its terminal point. Thus, if vector v has its initial point at the origin and its terminal point at

we write the vector in component form as

When a vector is written in component form like this, the scalars x and y are called the components of

The vector with initial point

and terminal point

can be written in component form as

The scalars

and

are called the components of

Recall that vectors are named with lowercase letters in bold type or by drawing an arrow over their name. We have also learned that we can name a vector by its component form, with the coordinates of its terminal point in angle brackets. However, when writing the component form of a vector, it is important to distinguish between

and

The first ordered pair uses angle brackets to describe a vector, whereas the second uses parentheses to describe a point in a plane. The initial point of

is

the terminal point of

is

When we have a vector not already in standard position, we can determine its component form in one of two ways. We can use a geometric approach, in which we sketch the vector in the coordinate plane, and then sketch an equivalent standard-position vector. Alternatively, we can find it algebraically, using the coordinates of the initial point and the terminal point. To find it algebraically, we subtract the x-coordinate of the initial point from the x-coordinate of the terminal point to get the x component, and we subtract the y-coordinate of the initial point from the y-coordinate of the terminal point to get the y component.

Let v be a vector with initial point

and terminal point

Then we can express v in component form as

Express vector

with initial point

and terminal point

in component form.

and terminal point

In the first solution, we used a sketch of the vector to see that the terminal point lies 4 units to the right. We can accomplish this algebraically by finding the difference of the x-coordinates:

Similarly, the difference of the y-coordinates shows the vertical length of the vector.

So, in component form,

Vector

has initial point

and terminal point

Express

in component form.

You may use either geometric or algebraic method.

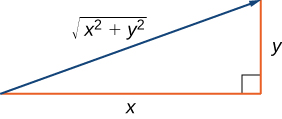

To find the magnitude of a vector, we calculate the distance between its initial point and its terminal point. The magnitude of vector

is denoted

or

and can be computed using the formula

Note that because this vector is written in component form, it is equivalent to a vector in standard position, with its initial point at the origin and terminal point

Thus, it suffices to calculate the magnitude of the vector in standard position. Using the distance formula to calculate the distance between initial point

and terminal point

we have

Based on this formula, it is clear that for any vector

and

if and only if

The magnitude of a vector can also be derived using the Pythagorean theorem, as in the following figure.

We have defined scalar multiplication and vector addition geometrically. Expressing vectors in component form allows us to perform these same operations algebraically.

Let

and

be vectors, and let

be a scalar.

Scalar multiplication:

Vector addition:

Let

be the vector with initial point

and terminal point

and let

in component form and find

Then, using algebra, find

and

at the origin, we must translate the vector

units to the left and

units down ([link]). Using the algebraic method, we can express

as

add the x-components and the y-components separately:

multiply

by the scalar

find

and add it to

Let

and let

be the vector with initial point

and terminal point

in component form.

a.

b.

c.

Use the Pythagorean Theorem to find

To find

start by finding the scalar multiples

and

Now that we have established the basic rules of vector arithmetic, we can state the properties of vector operations. We will prove two of these properties. The others can be proved in a similar manner.

Let

be vectors in a plane. Let

be scalars.

Let

and

Apply the commutative property for real numbers:

□

Apply the distributive property for real numbers:

□

Prove the additive inverse property.

Use the component form of the vectors.

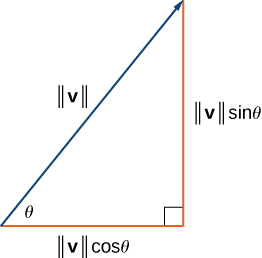

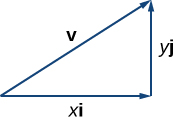

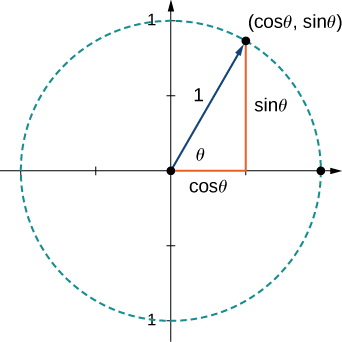

We have found the components of a vector given its initial and terminal points. In some cases, we may only have the magnitude and direction of a vector, not the points. For these vectors, we can identify the horizontal and vertical components using trigonometry ([link]).

Consider the angle

formed by the vector v and the positive x-axis. We can see from the triangle that the components of vector

are

Therefore, given an angle and the magnitude of a vector, we can use the cosine and sine of the angle to find the components of the vector.

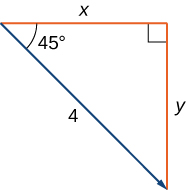

Find the component form of a vector with magnitude 4 that forms an angle of

with the x-axis.

Let

and

represent the components of the vector ([link]). Then

and

The component form of the vector is

Find the component form of vector

with magnitude

that forms an angle of

with the positive x-axis.

and

A unit vector is a vector with magnitude

For any nonzero vector

we can use scalar multiplication to find a unit vector

that has the same direction as

To do this, we multiply the vector by the reciprocal of its magnitude:

Recall that when we defined scalar multiplication, we noted that

For

it follows that

We say that

is the unit vector in the direction of

([link]). The process of using scalar multiplication to find a unit vector with a given direction is called normalization.

Let

with the same direction as

such that

then divide the components of

by the magnitude:

is in the same direction as

and

Use scalar multiplication to increase the length of

without changing direction:

Let

Find a vector with magnitude

in the opposite direction as

First, find a unit vector in the same direction as

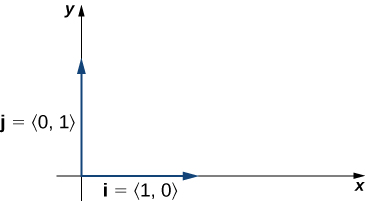

We have seen how convenient it can be to write a vector in component form. Sometimes, though, it is more convenient to write a vector as a sum of a horizontal vector and a vertical vector. To make this easier, let’s look at standard unit vectors. The standard unit vectors are the vectors

and

([link]).

By applying the properties of vectors, it is possible to express any vector in terms of

and

in what we call a linear combination:

Thus,

is the sum of a horizontal vector with magnitude

and a vertical vector with magnitude

as in the following figure.

in terms of standard unit vectors.

is a unit vector that forms an angle of

with the positive x-axis. Use standard unit vectors to describe

into a vector with a zero y-component and a vector with a zero x-component:

is a unit vector, the terminal point lies on the unit circle when the vector is placed in standard position ([link]).

Let

and let

be a unit vector that forms an angle of

with the positive x-axis. Express

and

in terms of the standard unit vectors.

Use sine and cosine to find the components of

Because vectors have both direction and magnitude, they are valuable tools for solving problems involving such applications as motion and force. Recall the boat example and the quarterback example we described earlier. Here we look at two other examples in detail.

Jane’s car is stuck in the mud. Lisa and Jed come along in a truck to help pull her out. They attach one end of a tow strap to the front of the car and the other end to the truck’s trailer hitch, and the truck starts to pull. Meanwhile, Jane and Jed get behind the car and push. The truck generates a horizontal force of

lb on the car. Jane and Jed are pushing at a slight upward angle and generate a force of

lb on the car. These forces can be represented by vectors, as shown in [link]. The angle between these vectors is

Find the resultant force (the vector sum) and give its magnitude to the nearest tenth of a pound and its direction angle from the positive x-axis.

To find the effect of combining the two forces, add their representative vectors. First, express each vector in component form or in terms of the standard unit vectors. For this purpose, it is easiest if we align one of the vectors with the positive x-axis. The horizontal vector, then, has initial point

and terminal point

It can be expressed as

or

The second vector has magnitude

and makes an angle of

with the first, so we can express it as

or

Then, the sum of the vectors, or resultant vector, is

and we have

The angle

made by

and the positive x-axis has

so

which means the resultant force

has an angle of

above the horizontal axis.

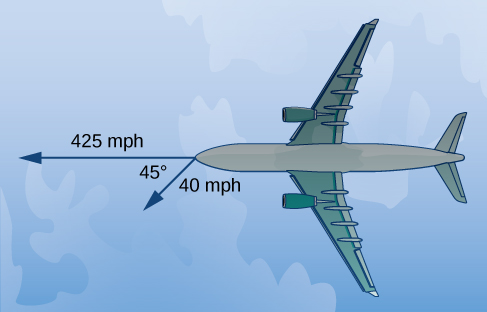

An airplane flies due west at an airspeed of

mph. The wind is blowing from the northeast at

mph. What is the ground speed of the airplane? What is the bearing of the airplane?

Let’s start by sketching the situation described ([link]).

Set up a sketch so that the initial points of the vectors lie at the origin. Then, the plane’s velocity vector is

The vector describing the wind makes an angle of

with the positive x-axis:

When the airspeed and the wind act together on the plane, we can add their vectors to find the resultant force:

The magnitude of the resultant vector shows the effect of the wind on the ground speed of the airplane:

As a result of the wind, the plane is traveling at approximately

mph relative to the ground.

To determine the bearing of the airplane, we want to find the direction of the vector

The overall direction of the plane is

south of west.

An airplane flies due north at an airspeed of

mph. The wind is blowing from the northwest at

mph. What is the ground speed of the airplane?

Approximately

mph

Sketch the vectors with the same initial point and find their sum.

has magnitude

and can be found by dividing a vector by its magnitude:

The standard unit vectors are

A vector

can be expressed in terms of the standard unit vectors as

For the following exercises, consider points

and

Determine the requested vectors and express each of them a. in component form and b. by using the standard unit vectors.

a.

b.

a.

b.

a.

b.

a.

b.

The unit vector in the direction of

a.

b.

The unit vector in the direction of

A vector

has initial point

and terminal point

Find the unit vector in the direction of

Express the answer in component form.

A vector

has initial point

and terminal point

Find the unit vector in the direction of

Express the answer in component form.

The vector

has initial point

and terminal point

that is on the y-axis and above the initial point. Find the coordinates of terminal point

such that the magnitude of the vector

is

The vector

has initial point

and terminal point

that is on the x-axis and left of the initial point. Find the coordinates of terminal point

such that the magnitude of the vector

is

For the following exercises, use the given vectors

and

and express it in both the component form and by using the standard unit vectors.

and express it in both the component form and by using the standard unit vectors.

and

and, respectively,

and

satisfy the triangle inequality.

and

Express the vectors in both the component form and by using standard unit vectors.

a.

b.

c. Answers will vary; d.

Let

be a standard-position vector with terminal point

Let

be a vector with initial point

and terminal point

Find the magnitude of vector

Let

be a standard-position vector with terminal point at

Let

be a vector with initial point

and terminal point

Find the magnitude of vector

Let

and

be two nonzero vectors that are nonequivalent. Consider the vectors

and

defined in terms of

and

Find the scalar

such that vectors

and

are equivalent.

Let

and

be two nonzero vectors that are nonequivalent. Consider the vectors

and

defined in terms of

and

Find the scalars

and

such that vectors

and

are equivalent.

Consider the vector

with components that depend on a real number

As the number

varies, the components of

change as well, depending on the functions that define them.

and

in component form.

of vector

remains constant for any real number

varies, show that the terminal point of vector

describes a circle centered at the origin of radius

a.

b. Answers may vary; c. Answers may vary

Consider vector

with components that depend on a real number

As the number

varies, the components of

change as well, depending on the functions that define them.

and

in component form.

of vector

remains constant for any real number

varies, show that the terminal point of vector

describes a circle centered at the origin of radius

Show that vectors

and

are equivalent for

and

where

is an integer.

Answers may vary

Show that vectors

and

are opposite for

and

where

is an integer.

For the following exercises, find vector

with the given magnitude and in the same direction as vector

For the following exercises, find the component form of vector

given its magnitude and the angle the vector makes with the positive x-axis. Give exact answers when possible.

For the following exercises, vector

is given. Find the angle

that vector

makes with the positive direction of the x-axis, in a counter-clockwise direction.

Let

and

be three nonzero vectors. If

then show there are two scalars,

and

such that

Answers may vary

Consider vectors

and c = 0 Determine the scalars

and

such that

Let

be a fixed point on the graph of the differential function

with a domain that is the set of real numbers.

such that point

is situated on the line tangent to the graph of

at point

with initial point

and terminal point

a.

b.

Consider the function

where

such that point

s situated on the line tangent to the graph of

at point

with initial point

and terminal point

Consider

and

two functions defined on the same set of real numbers

Let

and

be two vectors that describe the graphs of the functions, where

Show that if the graphs of the functions

and

do not intersect, then the vectors

and

are not equivalent.

Find

such that vectors

and

are equivalent.

Calculate the coordinates of point

such that

is a parallelogram, with

and

Consider the points

and

Determine the component form of vector

The speed of an object is the magnitude of its related velocity vector. A football thrown by a quarterback has an initial speed of

mph and an angle of elevation of

Determine the velocity vector in mph and express it in component form. (Round to two decimal places.)

A baseball player throws a baseball at an angle of

with the horizontal. If the initial speed of the ball is

mph, find the horizontal and vertical components of the initial velocity vector of the baseball. (Round to two decimal places.)

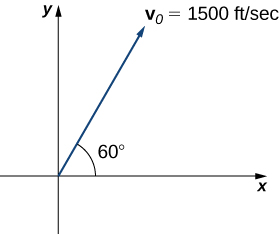

A bullet is fired with an initial velocity of

ft/sec at an angle of

with the horizontal. Find the horizontal and vertical components of the velocity vector of the bullet. (Round to two decimal places.)

The horizontal and vertical components are

ft/sec and

ft/sec, respectively.

[T] A 65-kg sprinter exerts a force of

N at a

angle with respect to the ground on the starting block at the instant a race begins. Find the horizontal component of the force. (Round to two decimal places.)

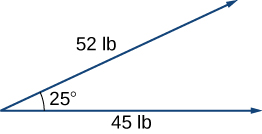

[T] Two forces, a horizontal force of

lb and another of

lb, act on the same object. The angle between these forces is

Find the magnitude and direction angle from the positive x-axis of the resultant force that acts on the object. (Round to two decimal places.)

The magnitude of resultant force is

lb; the direction angle is

[T] Two forces, a vertical force of

lb and another of

lb, act on the same object. The angle between these forces is

Find the magnitude and direction angle from the positive x-axis of the resultant force that acts on the object. (Round to two decimal places.)

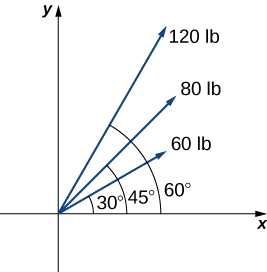

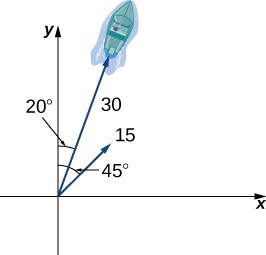

[T] Three forces act on object. Two of the forces have the magnitudes

N and

N, and make angles

and

respectively, with the positive x-axis. Find the magnitude and the direction angle from the positive x-axis of the third force such that the resultant force acting on the object is zero. (Round to two decimal places.)

The magnitude of the third vector is

N; the direction angle is

Three forces with magnitudes

lb,

lb, and

lb act on an object at angles of

and

respectively, with the positive x-axis. Find the magnitude and direction angle from the positive x-axis of the resultant force. (Round to two decimal places.)

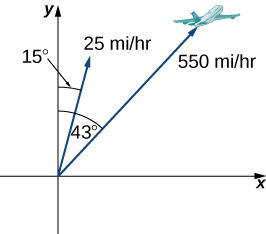

[T] An airplane is flying in the direction of

east of north (also abbreviated as

at a speed of

mph. A wind with speed

mph comes from the southwest at a bearing of

What are the ground speed and new direction of the airplane?

The new ground speed of the airplane is

mph; the new direction is

[T] A boat is traveling in the water at

mph in a direction of

(that is,

east of north). A strong current is moving at

mph in a direction of

What are the new speed and direction of the boat?

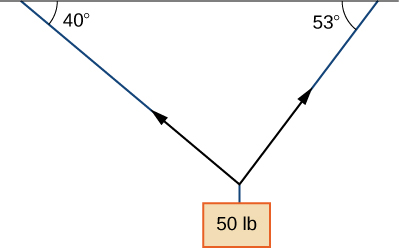

[T] A 50-lb weight is hung by a cable so that the two portions of the cable make angles of

and

respectively, with the horizontal. Find the magnitudes of the forces of tension

and

in the cables if the resultant force acting on the object is zero. (Round to two decimal places.)

[T] A 62-lb weight hangs from a rope that makes the angles of

and

respectively, with the horizontal. Find the magnitudes of the forces of tension

and

in the cables if the resultant force acting on the object is zero. (Round to two decimal places.)

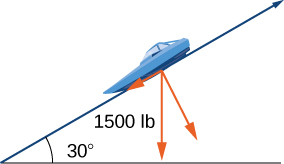

[T] A 1500-lb boat is parked on a ramp that makes an angle of

with the horizontal. The boat’s weight vector points downward and is a sum of two vectors: a horizontal vector

that is parallel to the ramp and a vertical vector

that is perpendicular to the inclined surface. The magnitudes of vectors

and

are the horizontal and vertical component, respectively, of the boat’s weight vector. Find the magnitudes of

and

(Round to the nearest integer.)

lb,

lb

[T] An 85-lb box is at rest on a

incline. Determine the magnitude of the force parallel to the incline necessary to keep the box from sliding. (Round to the nearest integer.)

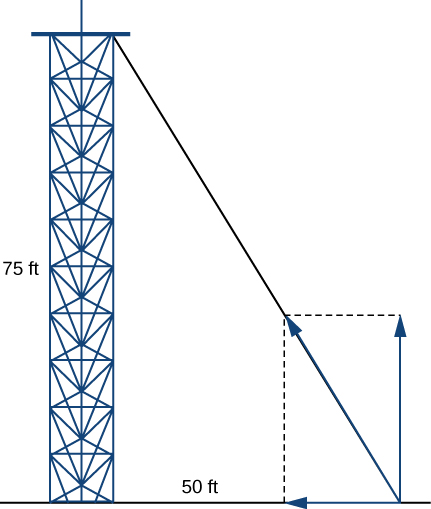

A guy-wire supports a pole that is

ft high. One end of the wire is attached to the top of the pole and the other end is anchored to the ground

ft from the base of the pole. Determine the horizontal and vertical components of the force of tension in the wire if its magnitude is

lb. (Round to the nearest integer.)

The two horizontal and vertical components of the force of tension are

lb and

lb, respectively.

A telephone pole guy-wire has an angle of elevation of

with respect to the ground. The force of tension in the guy-wire is

lb. Find the horizontal and vertical components of the force of tension. (Round to the nearest integer.)

is defined as

and

can be constructed graphically by placing the initial point of

at the terminal point of

then the vector sum

is the vector with an initial point that coincides with the initial point of

and with a terminal point that coincides with the terminal point of

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: