Vectors are useful tools for solving two-dimensional problems. Life, however, happens in three dimensions. To expand the use of vectors to more realistic applications, it is necessary to create a framework for describing three-dimensional space. For example, although a two-dimensional map is a useful tool for navigating from one place to another, in some cases the topography of the land is important. Does your planned route go through the mountains? Do you have to cross a river? To appreciate fully the impact of these geographic features, you must use three dimensions. This section presents a natural extension of the two-dimensional Cartesian coordinate plane into three dimensions.

As we have learned, the two-dimensional rectangular coordinate system contains two perpendicular axes: the horizontal x-axis and the vertical y-axis. We can add a third dimension, the z-axis, which is perpendicular to both the x-axis and the y-axis. We call this system the three-dimensional rectangular coordinate system. It represents the three dimensions we encounter in real life.

The three-dimensional rectangular coordinate system consists of three perpendicular axes: the x-axis, the y-axis, and the z-axis. Because each axis is a number line representing all real numbers in

the three-dimensional system is often denoted by

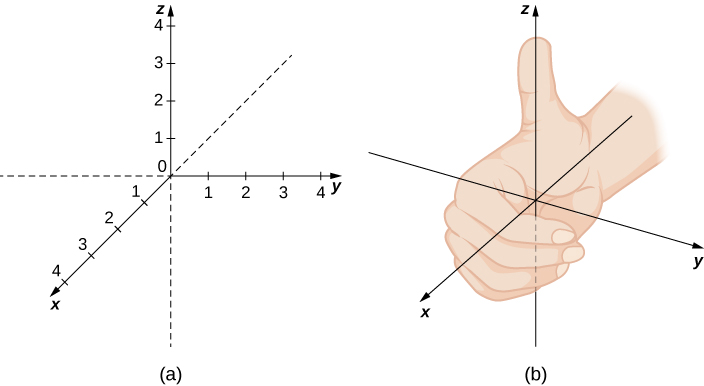

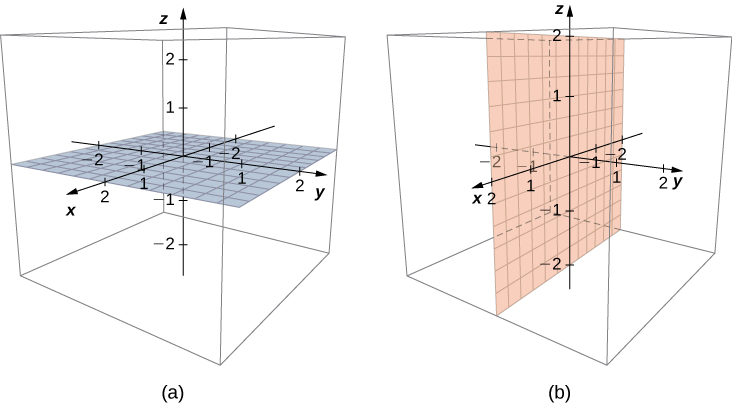

In [link](a), the positive z-axis is shown above the plane containing the x- and y-axes. The positive x-axis appears to the left and the positive y-axis is to the right. A natural question to ask is: How was arrangement determined? The system displayed follows the right-hand rule. If we take our right hand and align the fingers with the positive x-axis, then curl the fingers so they point in the direction of the positive y-axis, our thumb points in the direction of the positive z-axis. In this text, we always work with coordinate systems set up in accordance with the right-hand rule. Some systems do follow a left-hand rule, but the right-hand rule is considered the standard representation.

In two dimensions, we describe a point in the plane with the coordinates

Each coordinate describes how the point aligns with the corresponding axis. In three dimensions, a new coordinate,

is appended to indicate alignment with the z-axis:

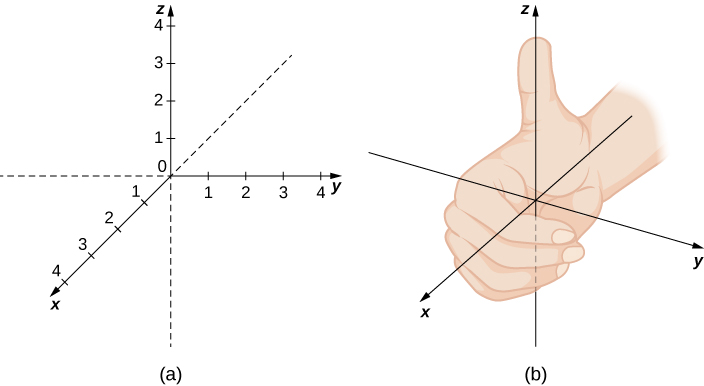

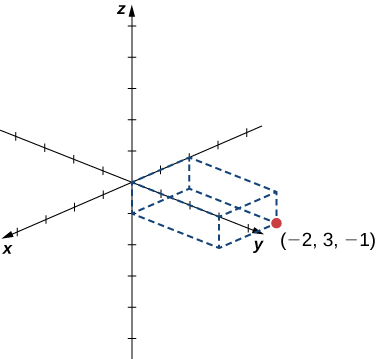

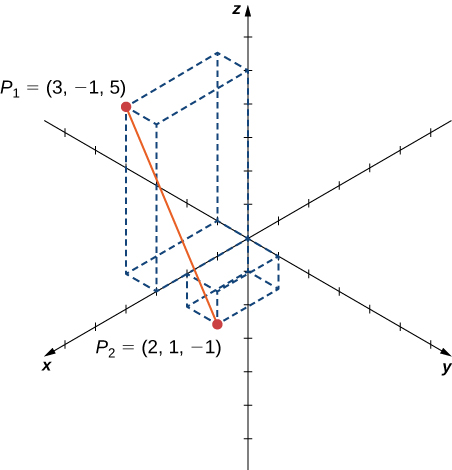

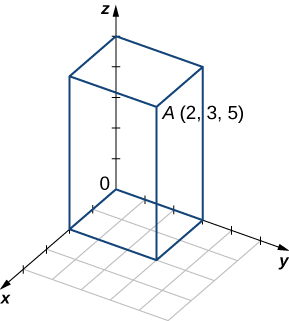

A point in space is identified by all three coordinates ([link]). To plot the point

go x units along the x-axis, then

units in the direction of the y-axis, then

units in the direction of the z-axis.

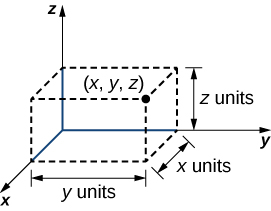

Sketch the point

in three-dimensional space.

To sketch a point, start by sketching three sides of a rectangular prism along the coordinate axes: one unit in the positive

direction,

units in the negative

direction, and

units in the positive

direction. Complete the prism to plot the point ([link]).

Sketch the point

in three-dimensional space.

Start by sketching the coordinate axes. Then sketch a rectangular prism to help find the point in space.

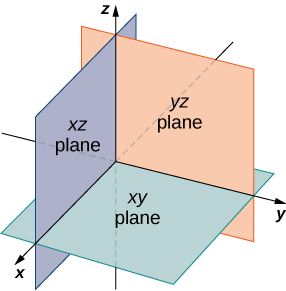

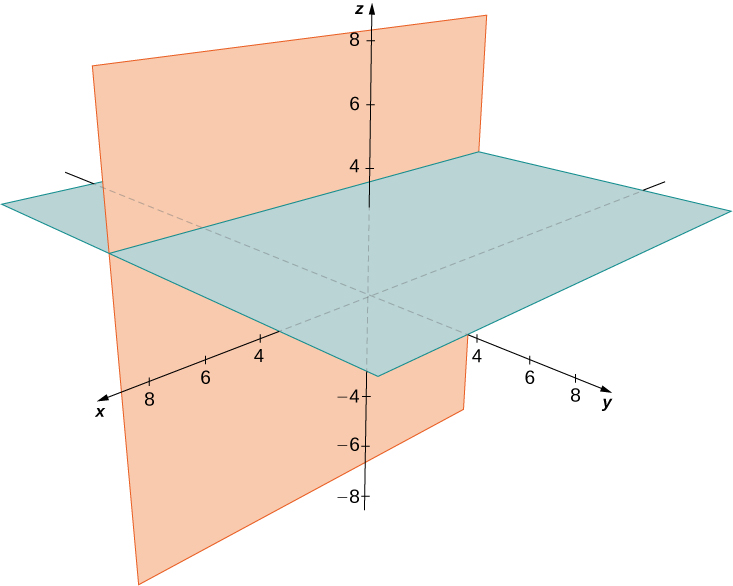

In two-dimensional space, the coordinate plane is defined by a pair of perpendicular axes. These axes allow us to name any location within the plane. In three dimensions, we define coordinate planes by the coordinate axes, just as in two dimensions. There are three axes now, so there are three intersecting pairs of axes. Each pair of axes forms a coordinate plane: the xy-plane, the xz-plane, and the yz-plane ([link]). We define the xy-plane formally as the following set:

Similarly, the xz-plane and the yz-plane are defined as

and

respectively.

To visualize this, imagine you’re building a house and are standing in a room with only two of the four walls finished. (Assume the two finished walls are adjacent to each other.) If you stand with your back to the corner where the two finished walls meet, facing out into the room, the floor is the xy-plane, the wall to your right is the xz-plane, and the wall to your left is the yz-plane.

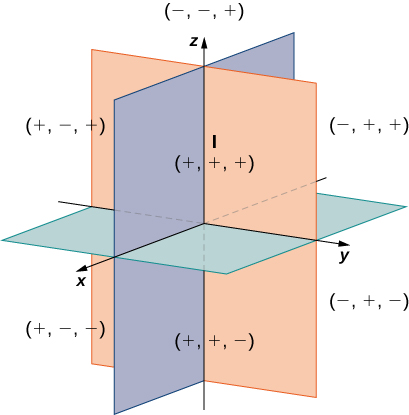

In two dimensions, the coordinate axes partition the plane into four quadrants. Similarly, the coordinate planes divide space between them into eight regions about the origin, called octants. The octants fill

in the same way that quadrants fill

as shown in [link].

Most work in three-dimensional space is a comfortable extension of the corresponding concepts in two dimensions. In this section, we use our knowledge of circles to describe spheres, then we expand our understanding of vectors to three dimensions. To accomplish these goals, we begin by adapting the distance formula to three-dimensional space.

If two points lie in the same coordinate plane, then it is straightforward to calculate the distance between them. We that the distance

between two points

and

in the xy-coordinate plane is given by the formula

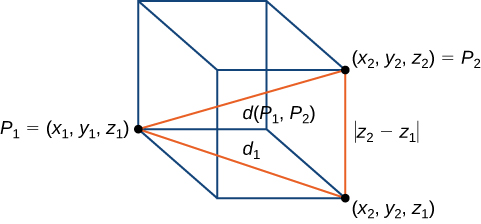

The formula for the distance between two points in space is a natural extension of this formula.

The distance

between points

and

is given by the formula

The proof of this theorem is left as an exercise. (Hint: First find the distance

between the points

and

as shown in [link].)

Find the distance between points

and

Substitute values directly into the distance formula:

Find the distance between points

and

Before moving on to the next section, let’s get a feel for how

differs from

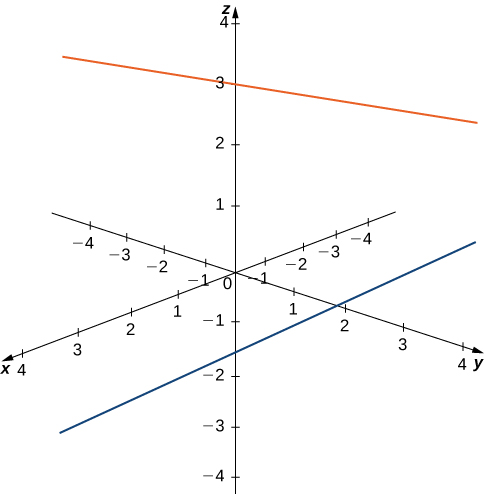

For example, in

lines that are not parallel must always intersect. This is not the case in

For example, consider the line shown in [link]. These two lines are not parallel, nor do they intersect.

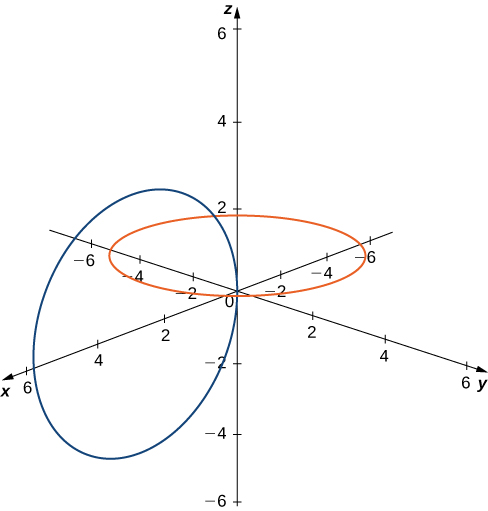

You can also have circles that are interconnected but have no points in common, as in [link].

We have a lot more flexibility working in three dimensions than we do if we stuck with only two dimensions.

Now that we can represent points in space and find the distance between them, we can learn how to write equations of geometric objects such as lines, planes, and curved surfaces in

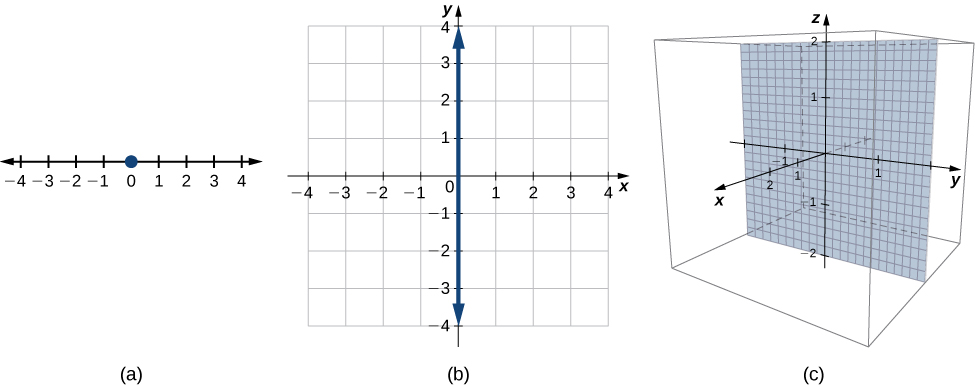

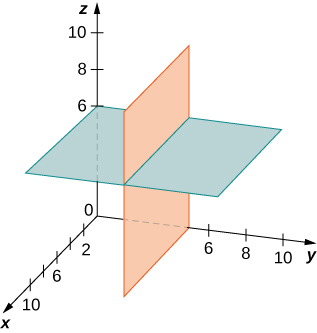

First, we start with a simple equation. Compare the graphs of the equation

in

([link]). From these graphs, we can see the same equation can describe a point, a line, or a plane.

In space, the equation

describes all points

This equation defines the yz-plane. Similarly, the xy-plane contains all points of the form

The equation

defines the xy-plane and the equation

describes the xz-plane ([link]).

Understanding the equations of the coordinate planes allows us to write an equation for any plane that is parallel to one of the coordinate planes. When a plane is parallel to the xy-plane, for example, the z-coordinate of each point in the plane has the same constant value. Only the x- and y-coordinates of points in that plane vary from point to point.

can be represented by the equation

can be represented by the equation

can be represented by the equation

that is parallel to the yz-plane.

and

and

has the same y-coordinate. This plane can be represented by the equation

Write an equation of the plane passing through point

that is parallel to the xy-plane.

If a plane is parallel to the xy-plane, the z-coordinates of the points in that plane do not vary.

As we have seen, in

the equation

describes the vertical line passing through point

This line is parallel to the y-axis. In a natural extension, the equation

in

describes the plane passing through point

which is parallel to the yz-plane. Another natural extension of a familiar equation is found in the equation of a sphere.

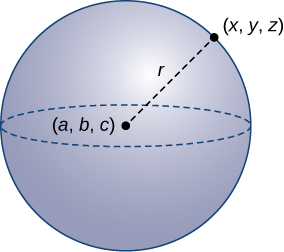

A sphere is the set of all points in space equidistant from a fixed point, the center of the sphere ([link]), just as the set of all points in a plane that are equidistant from the center represents a circle. In a sphere, as in a circle, the distance from the center to a point on the sphere is called the radius.

The equation of a circle is derived using the distance formula in two dimensions. In the same way, the equation of a sphere is based on the three-dimensional formula for distance.

The sphere with center

and radius

can be represented by the equation

This equation is known as the standard equation of a sphere.

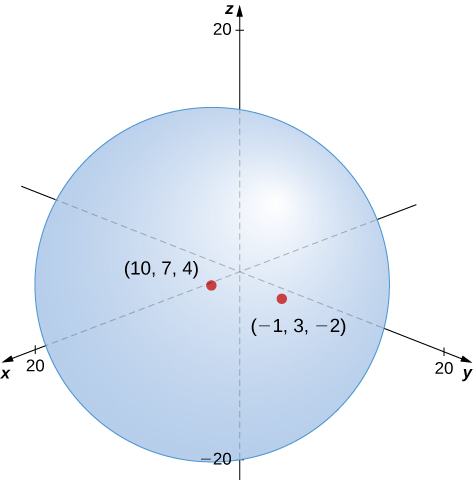

Find the standard equation of the sphere with center

and point

as shown in [link].

Use the distance formula to find the radius

of the sphere:

The standard equation of the sphere is

Find the standard equation of the sphere with center

containing point

First use the distance formula to find the radius of the sphere.

Let

and

and suppose line segment

forms the diameter of a sphere ([link]). Find the equation of the sphere.

Since

is a diameter of the sphere, we know the center of the sphere is the midpoint of

Then,

Furthermore, we know the radius of the sphere is half the length of the diameter. This gives

Then, the equation of the sphere is

Find the equation of the sphere with diameter

where

and

Find the midpoint of the diameter first.

Describe the set of points that satisfies

and graph the set.

Describe the set of points that satisfies

and graph the set.

The set of points forms the two planes

and

One of the factors must be zero.

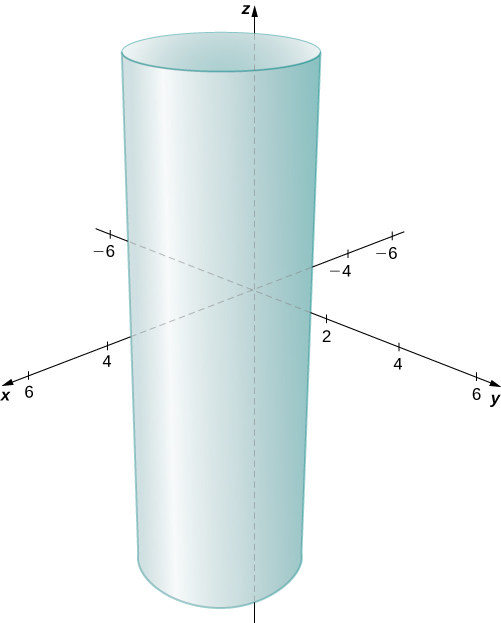

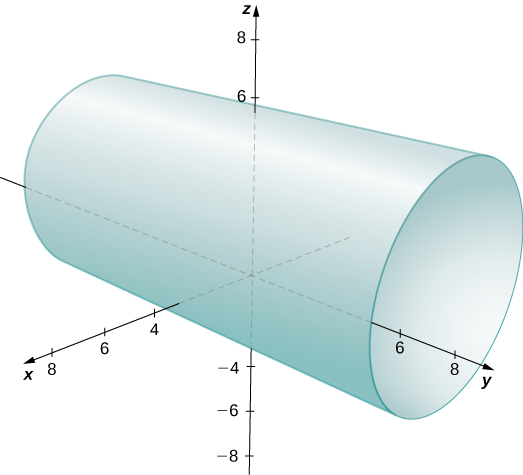

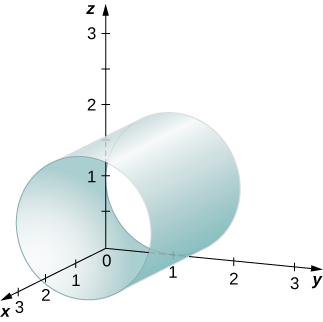

Describe the set of points in three-dimensional space that satisfies

and graph the set.

The x- and y-coordinates form a circle in the xy-plane of radius

centered at

Since there is no restriction on the z-coordinate, the three-dimensional result is a circular cylinder of radius

centered on the line with

The cylinder extends indefinitely in the z-direction ([link]).

Describe the set of points in three dimensional space that satisfies

and graph the surface.

A cylinder of radius 4 centered on the line with

Think about what happens if you plot this equation in two dimensions in the xz-plane.

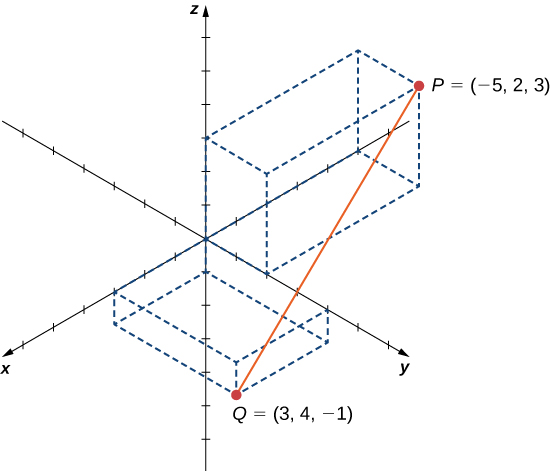

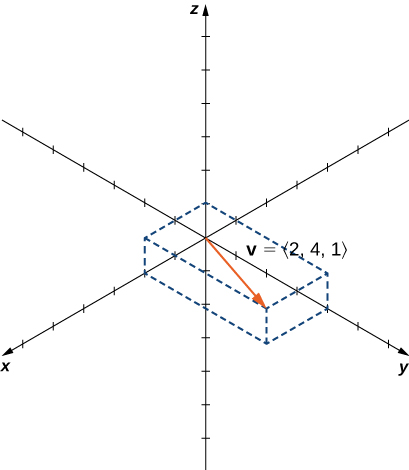

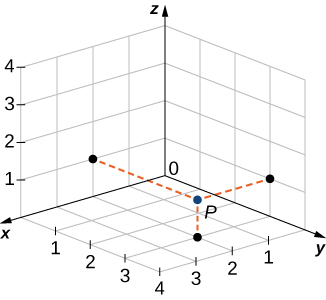

Just like two-dimensional vectors, three-dimensional vectors are quantities with both magnitude and direction, and they are represented by directed line segments (arrows). With a three-dimensional vector, we use a three-dimensional arrow.

Three-dimensional vectors can also be represented in component form. The notation

is a natural extension of the two-dimensional case, representing a vector with the initial point at the origin,

and terminal point

The zero vector is

So, for example, the three dimensional vector

is represented by a directed line segment from point

to point

([link]).

Vector addition and scalar multiplication are defined analogously to the two-dimensional case. If

and

are vectors, and

is a scalar, then

If

then

is written as

and vector subtraction is defined by

The standard unit vectors extend easily into three dimensions as well—

and

—and we use them in the same way we used the standard unit vectors in two dimensions. Thus, we can represent a vector in

in the following ways:

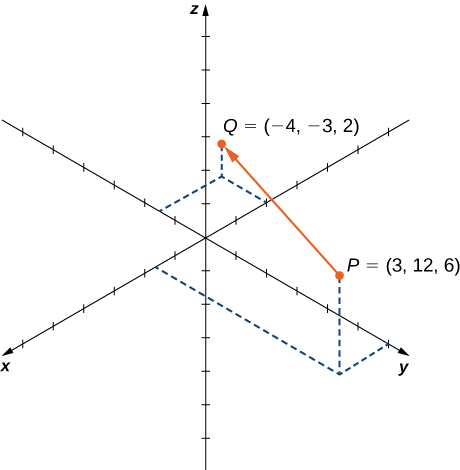

Let

be the vector with initial point

and terminal point

as shown in [link]. Express

in both component form and using standard unit vectors.

In component form,

In standard unit form,

Let

and

Express

in component form and in standard unit form.

Write

in component form first.

is the terminal point of

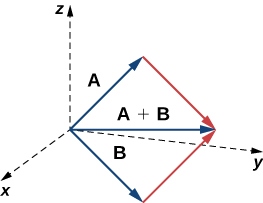

As described earlier, vectors in three dimensions behave in the same way as vectors in a plane. The geometric interpretation of vector addition, for example, is the same in both two- and three-dimensional space ([link]).

We have already seen how some of the algebraic properties of vectors, such as vector addition and scalar multiplication, can be extended to three dimensions. Other properties can be extended in similar fashion. They are summarized here for our reference.

Let

and

be vectors, and let

be a scalar.

Scalar multiplication:

Vector addition:

Vector subtraction:

Vector magnitude:

Unit vector in the direction of v:

if

We have seen that vector addition in two dimensions satisfies the commutative, associative, and additive inverse properties. These properties of vector operations are valid for three-dimensional vectors as well. Scalar multiplication of vectors satisfies the distributive property, and the zero vector acts as an additive identity. The proofs to verify these properties in three dimensions are straightforward extensions of the proofs in two dimensions.

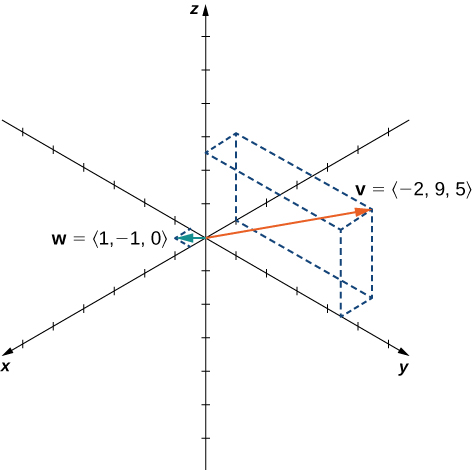

Let

and

([link]). Find the following vectors.

Let

and

Find a unit vector in the direction of

Start by writing

in component form.

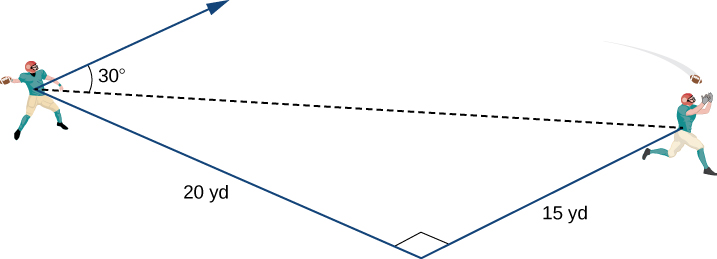

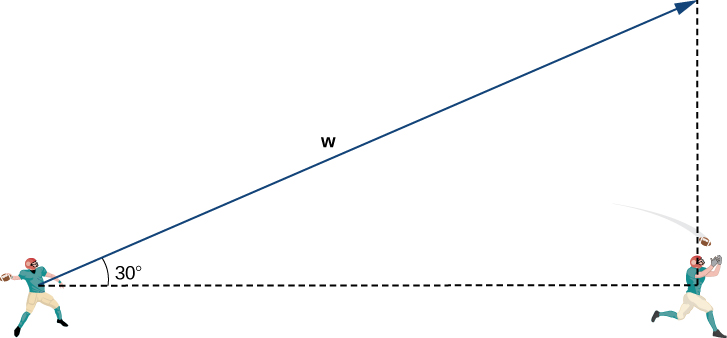

A quarterback is standing on the football field preparing to throw a pass. His receiver is standing 20 yd down the field and 15 yd to the quarterback’s left. The quarterback throws the ball at a velocity of 60 mph toward the receiver at an upward angle of

(see the following figure). Write the initial velocity vector of the ball,

in component form.

The first thing we want to do is find a vector in the same direction as the velocity vector of the ball. We then scale the vector appropriately so that it has the right magnitude. Consider the vector

extending from the quarterback’s arm to a point directly above the receiver’s head at an angle of

(see the following figure). This vector would have the same direction as

but it may not have the right magnitude.

The receiver is 20 yd down the field and 15 yd to the quarterback’s left. Therefore, the straight-line distance from the quarterback to the receiver is

The receiver is 20 yd down the field and 15 yd to the quarterback’s left. Therefore, the straight-line distance from the quarterback to the receiver is

We have

Then the magnitude of

is given by

and the vertical distance from the receiver to the terminal point of

is

Then

and has the same direction as

Recall, though, that we calculated the magnitude of

to be

and

has magnitude

mph. So, we need to multiply vector

by an appropriate constant,

We want to find a value of

so that

mph. We have

so we want

Then

Let’s double-check that

We have

So, we have found the correct components for

Assume the quarterback and the receiver are in the same place as in the previous example. This time, however, the quarterback throws the ball at velocity of

mph and an angle of

Write the initial velocity vector of the ball,

in component form.

Follow the process used in the previous example.

are used to describe the location of a point in space.

between points

and

is given by the formula

describe planes that are parallel to the coordinate planes.

and radius

is

or in terms of the standard unit vectors,

and

be vectors, and let

be a scalar.

**Sphere with center

and radius r:**

Consider a rectangular box with one of the vertices at the origin, as shown in the following figure. If point

is the opposite vertex to the origin, then find

and

a.

b.

Find the coordinates of point

and determine its distance to the origin.

For the following exercises, describe and graph the set of points that satisfies the given equation.

A union of two planes:

(a plane parallel to the xz-plane) and

(a plane parallel to the xy-plane)* * *

A cylinder of radius

centered on the line

Write the equation of the plane passing through point

that is parallel to the xy-plane.

Write the equation of the plane passing through point

that is parallel to the xz-plane.

Find an equation of the plane passing through points

and

Find an equation of the plane passing through points

and

For the following exercises, find the equation of the sphere in standard form that satisfies the given conditions.

Center

and radius

Center

and radius

Diameter

where

and

Diameter

where

and

For the following exercises, find the center and radius of the sphere with an equation in general form that is given.

Center

and radius

For the following exercises, express vector

with the initial point at

and the terminal point at

and

a.

b.

and

and

where

is the midpoint of the line segment

a.

b.

and

where

is the midpoint of the line segment

Find terminal point

of vector

with the initial point at

Find initial point

of vector

with the terminal point at

For the following exercises, use the given vectors

and

to find and express the vectors

and

in component form.

For the following exercises, vectors u and v are given. Find the magnitudes of vectors

and

where

is a real number.

where

is a real number.

For the following exercises, find the unit vector in the direction of the given vector

and express it using standard unit vectors.

where

and

where

where

and

where

and

Determine whether

and

are equivalent vectors, where

and

Equivalent vectors

Determine whether the vectors

and

are equivalent, where

and

For the following exercises, find vector

with a magnitude that is given and satisfies the given conditions.

and

have the same direction

and

have the same direction

and

have opposite directions for any

where

is a real number

and

have opposite directions for any

where

is a real number

Determine a vector of magnitude

in the direction of vector

where

and

Find a vector of magnitude

that points in the opposite direction than vector

where

and

Express the answer in component form.

Consider the points

and

where

and

are negative real numbers. Find

and

such that

Consider points

and

where

and

are positive real numbers. Find

and

such that

Let

be a point situated at an equal distance from points

and

Show that point

lies on the plane of equation

Let

be a point situated at an equal distance from the origin and point

Show that the coordinates of point

satisfy the equation

The points

and

are collinear (in this order) if the relation

is satisfied. Show that

and

are collinear points.

Show that points

and

are not collinear.

[T] A force

of

acts on a particle in the direction of the vector

where

and the positive direction of the x-axis. Express the answer in degrees rounded to the nearest integer.

a.

b.

[T] A force

of

acts on a box in the direction of the vector

where

and the positive direction of the x-axis.

If

is a force that moves an object from point

to another point

then the displacement vector is defined as

A metal container is lifted

m vertically by a constant force

Express the displacement vector

by using standard unit vectors.

A box is pulled

yd horizontally in the x-direction by a constant force

Find the displacement vector in component form.

The sum of the forces acting on an object is called the resultant or net force. An object is said to be in static equilibrium if the resultant force of the forces that act on it is zero. Let

and

be three forces acting on a box. Find the force

acting on the box such that the box is in static equilibrium. Express the answer in component form.

[T] Let

be

forces acting on a particle, with

Express the answer using standard unit vectors.

The force of gravity

acting on an object is given by

where m is the mass of the object (expressed in kilograms) and

is acceleration resulting from gravity, with

A 2-kg disco ball hangs by a chain from the ceiling of a room.

acting on the disco ball and find its magnitude.

in the chain and its magnitude.

Express the answers using standard unit vectors.

a.

N; b.

N

A 5-kg pendant chandelier is designed such that the alabaster bowl is held by four chains of equal length, as shown in the following figure.

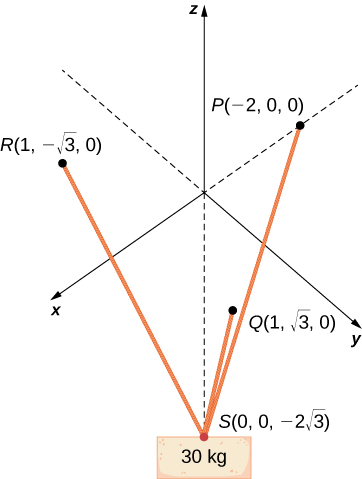

[T] A 30-kg block of cement is suspended by three cables of equal length that are anchored at points

and

The load is located at

as shown in the following figure. Let

and

be the forces of tension resulting from the load in cables

and

respectively.

acting on the block of cement that counterbalances the sum

of the forces of tension in the cables.

and

Express the answer in component form.

a.

N; b.

and

(each component is expressed in newtons)

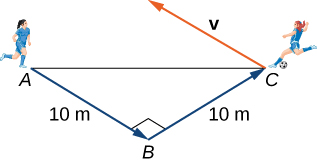

Two soccer players are practicing for an upcoming game. One of them runs 10 m from point A to point B. She then turns left at

and runs 10 m until she reaches point C. Then she kicks the ball with a speed of 10 m/sec at an upward angle of

to her teammate, who is located at point A. Write the velocity of the ball in component form.

Let

be the position vector of a particle at the time

where

and

are smooth functions on

The instantaneous velocity of the particle at time

is defined by vector

with components that are the derivatives with respect to

of the functions x, y, and z, respectively. The magnitude

of the instantaneous velocity vector is called the speed of the particle at time t. Vector

with components that are the second derivatives with respect to

of the functions

and

respectively, gives the acceleration of the particle at time

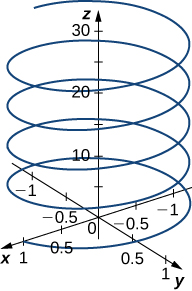

Consider

the position vector of a particle at time

where the components of

are expressed in centimeters and time is expressed in seconds.

where

a.

(each component is expressed in centimeters per second);

(expressed in centimeters per second);

(each component expressed in centimeters per second squared);

b.* * *

[T] Let

be the position vector of a particle at time

(in seconds), where

(here the components of

are expressed in centimeters).

where

describes a sphere with center

and radius

that plots its location relative to the defining axes

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: