The rectangular coordinate system (or Cartesian plane) provides a means of mapping points to ordered pairs and ordered pairs to points. This is called a one-to-one mapping from points in the plane to ordered pairs. The polar coordinate system provides an alternative method of mapping points to ordered pairs. In this section we see that in some circumstances, polar coordinates can be more useful than rectangular coordinates.

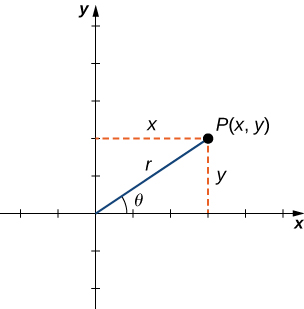

To find the coordinates of a point in the polar coordinate system, consider [link]. The point

has Cartesian coordinates

The line segment connecting the origin to the point

measures the distance from the origin to

and has length

The angle between the positive

-axis and the line segment has measure

This observation suggests a natural correspondence between the coordinate pair

and the values

and

This correspondence is the basis of the polar coordinate system. Note that every point in the Cartesian plane has two values (hence the term ordered pair) associated with it. In the polar coordinate system, each point also two values associated with it:

and

Using right-triangle trigonometry, the following equations are true for the point

Furthermore,

Each point

in the Cartesian coordinate system can therefore be represented as an ordered pair

in the polar coordinate system. The first coordinate is called the radial coordinate and the second coordinate is called the angular coordinate. Every point in the plane can be represented in this form.

Note that the equation

has an infinite number of solutions for any ordered pair

However, if we restrict the solutions to values between

and

then we can assign a unique solution to the quadrant in which the original point

is located. Then the corresponding value of r is positive, so

Given a point

in the plane with Cartesian coordinates

and polar coordinates

the following conversion formulas hold true:

These formulas can be used to convert from rectangular to polar or from polar to rectangular coordinates.

Convert each of the following points into polar coordinates.

Convert each of the following points into rectangular coordinates.

and

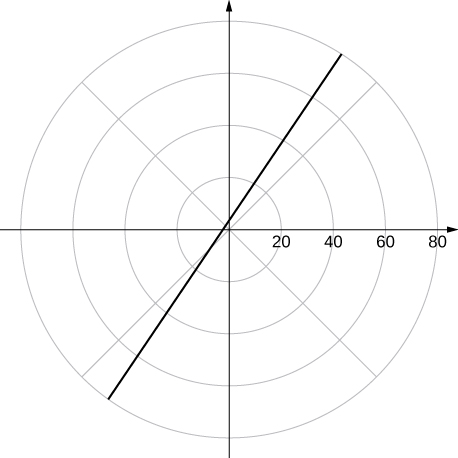

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in polar coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in polar coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Direct application of the second equation leads to division by zero. Graphing the point

on the rectangular coordinate system reveals that the point is located on the positive y-axis. The angle between the positive x-axis and the positive y-axis is

Therefore this point can be represented as

in polar coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in polar coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in rectangular coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in rectangular coordinates.

and

in [link]:

Therefore this point can be represented as

in rectangular coordinates.

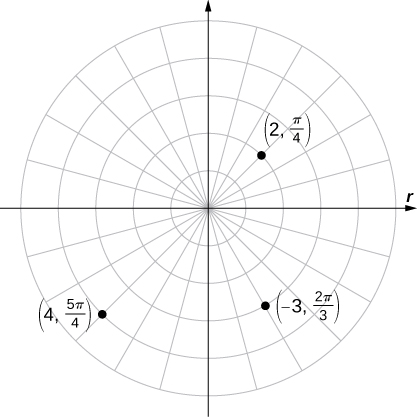

The polar representation of a point is not unique. For example, the polar coordinates

and

both represent the point

in the rectangular system. Also, the value of

can be negative. Therefore, the point with polar coordinates

also represents the point

in the rectangular system, as we can see by using [link]:

Every point in the plane has an infinite number of representations in polar coordinates. However, each point in the plane has only one representation in the rectangular coordinate system.

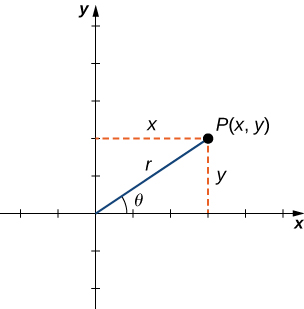

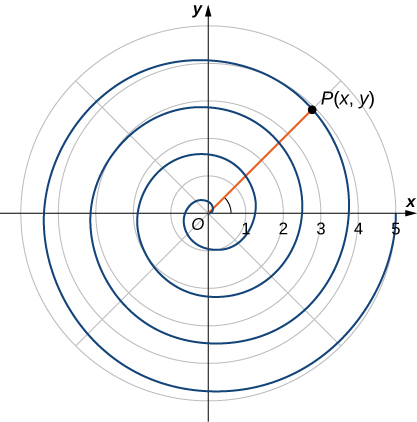

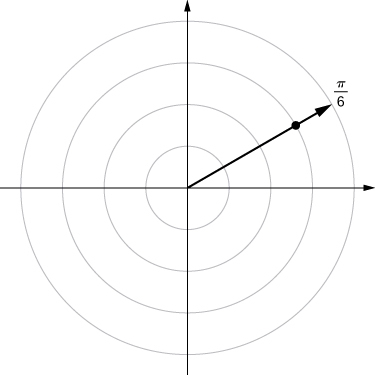

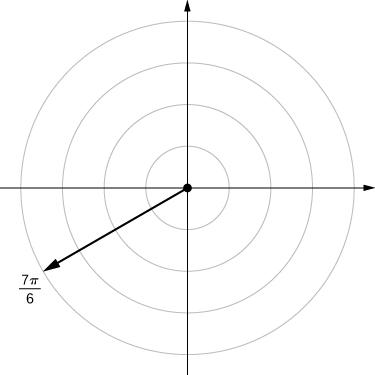

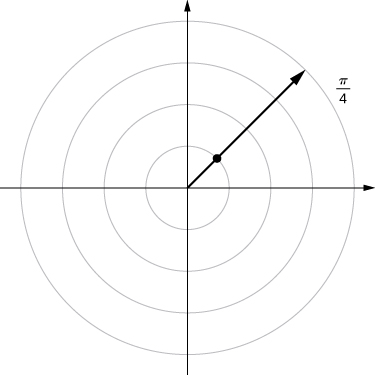

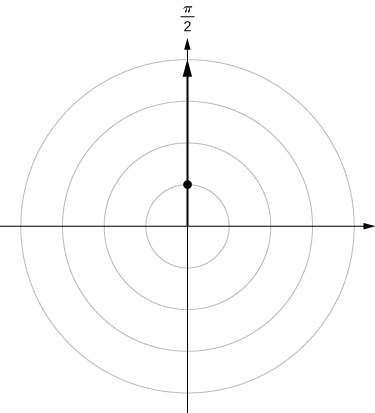

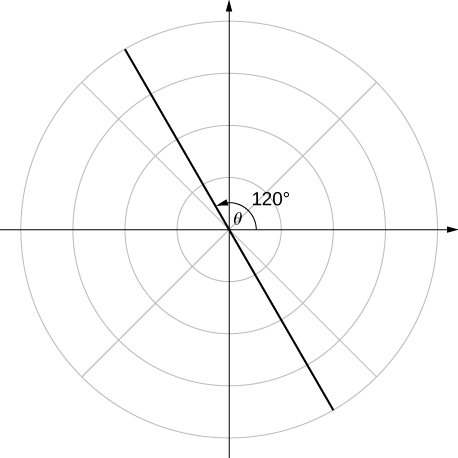

Note that the polar representation of a point in the plane also has a visual interpretation. In particular,

is the directed distance that the point lies from the origin, and

measures the angle that the line segment from the origin to the point makes with the positive

-axis. Positive angles are measured in a counterclockwise direction and negative angles are measured in a clockwise direction. The polar coordinate system appears in the following figure.

The line segment starting from the center of the graph going to the right (called the positive x-axis in the Cartesian system) is the polar axis. The center point is the pole, or origin, of the coordinate system, and corresponds to

The innermost circle shown in [link] contains all points a distance of 1 unit from the pole, and is represented by the equation

Then

is the set of points 2 units from the pole, and so on. The line segments emanating from the pole correspond to fixed angles. To plot a point in the polar coordinate system, start with the angle. If the angle is positive, then measure the angle from the polar axis in a counterclockwise direction. If it is negative, then measure it clockwise. If the value of

is positive, move that distance along the terminal ray of the angle. If it is negative, move along the ray that is opposite the terminal ray of the given angle.

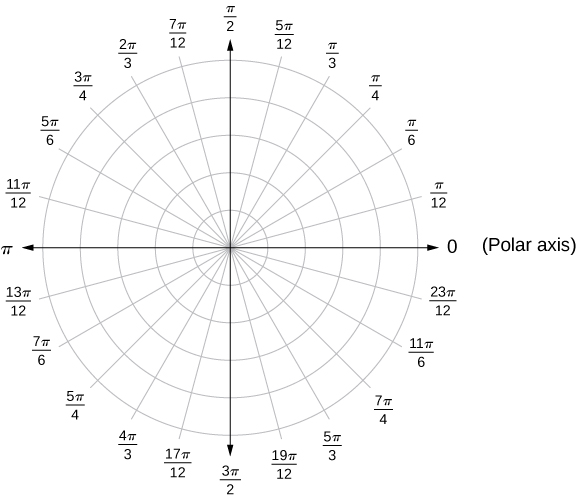

Plot each of the following points on the polar plane.

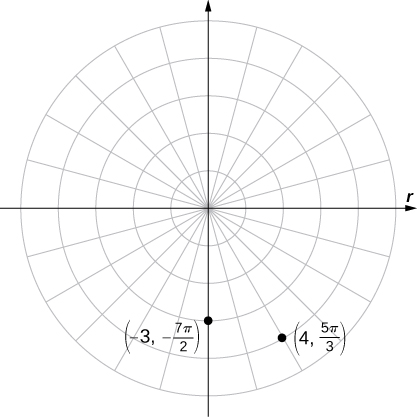

The three points are plotted in the following figure.

Plot

and

on the polar plane.

Start with

then use

Now that we know how to plot points in the polar coordinate system, we can discuss how to plot curves. In the rectangular coordinate system, we can graph a function

and create a curve in the Cartesian plane. In a similar fashion, we can graph a curve that is generated by a function

The general idea behind graphing a function in polar coordinates is the same as graphing a function in rectangular coordinates. Start with a list of values for the independent variable

in this case) and calculate the corresponding values of the dependent variable

This process generates a list of ordered pairs, which can be plotted in the polar coordinate system. Finally, connect the points, and take advantage of any patterns that may appear. The function may be periodic, for example, which indicates that only a limited number of values for the independent variable are needed.

and the second column is for

values for each

on the coordinate axes.

Watch this video for more information on sketching polar curves.

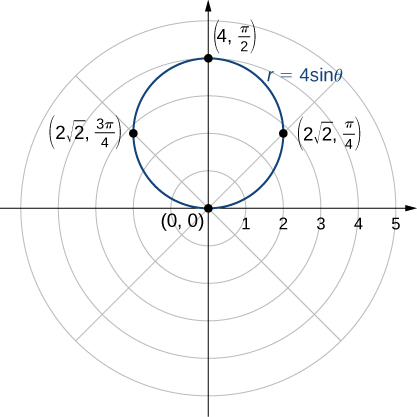

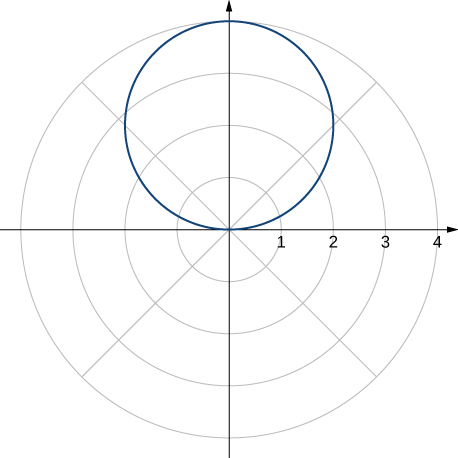

Graph the curve defined by the function

Identify the curve and rewrite the equation in rectangular coordinates.

Because the function is a multiple of a sine function, it is periodic with period

so use values for

between 0 and

The result of steps 1–3 appear in the following table. [link] shows the graph based on this table.

| 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 0 |

This is the graph of a circle. The equation

can be converted into rectangular coordinates by first multiplying both sides by

This gives the equation

Next use the facts that

and

This gives

To put this equation into standard form, subtract

from both sides of the equation and complete the square:

This is the equation of a circle with radius 2 and center

in the rectangular coordinate system.

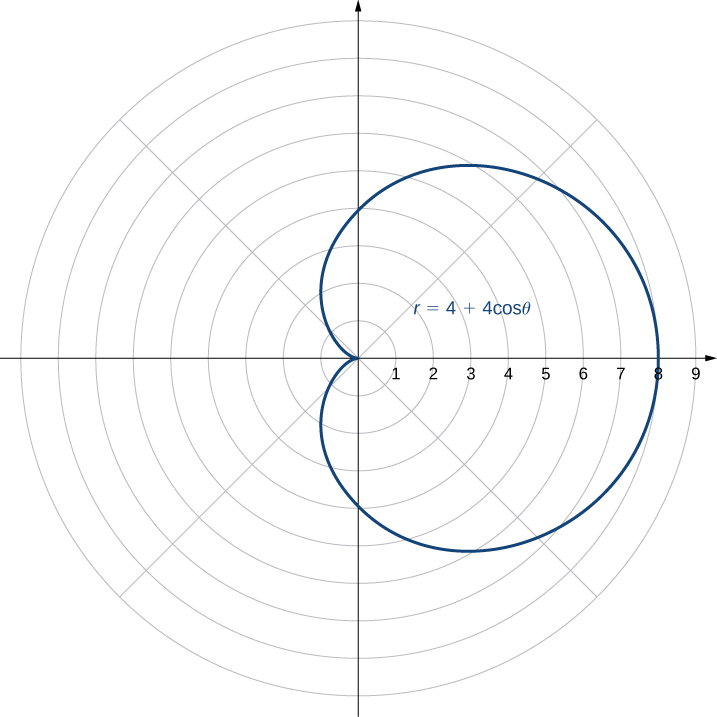

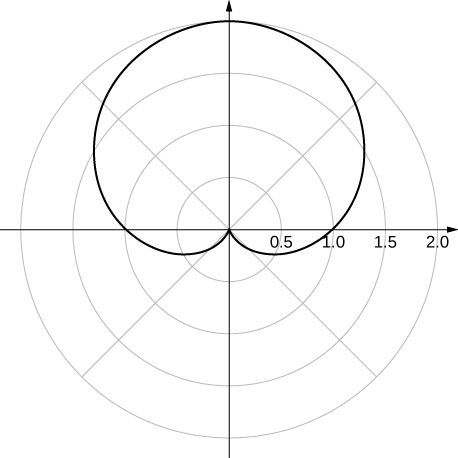

Create a graph of the curve defined by the function

The name of this shape is a cardioid, which we will study further later in this section.

Follow the problem-solving strategy for creating a graph in polar coordinates.

The graph in [link] was that of a circle. The equation of the circle can be transformed into rectangular coordinates using the coordinate transformation formulas in [link]. [link] gives some more examples of functions for transforming from polar to rectangular coordinates.

Rewrite each of the following equations in rectangular coordinates and identify the graph.

Since

we can replace the left-hand side of this equation by

This gives

which can be rewritten as

This is the equation of a straight line passing through the origin with slope

In general, any polar equation of the form

represents a straight line through the pole with slope equal to

Next replace

with

This gives the equation

which is the equation of a circle centered at the origin with radius 3. In general, any polar equation of the form

where k is a positive constant represents a circle of radius k centered at the origin. (Note: when squaring both sides of an equation it is possible to introduce new points unintentionally. This should always be taken into consideration. However, in this case we do not introduce new points. For example,

is the same point as

This leads to

Next use the formulas

This gives

To put this equation into standard form, first move the variables from the right-hand side of the equation to the left-hand side, then complete the square.

This is the equation of a circle with center at

and radius 5. Notice that the circle passes through the origin since the center is 5 units away.

Rewrite the equation

in rectangular coordinates and identify its graph.

which is the equation of a parabola opening upward.

Convert to sine and cosine, then multiply both sides by cosine.

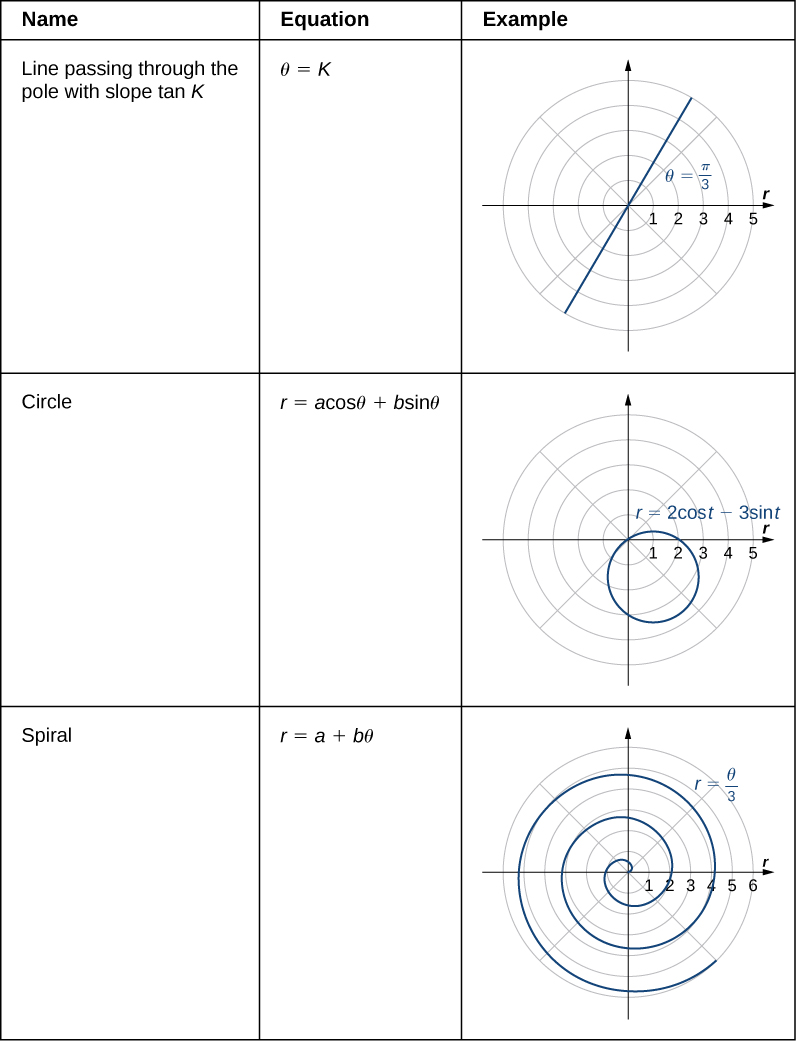

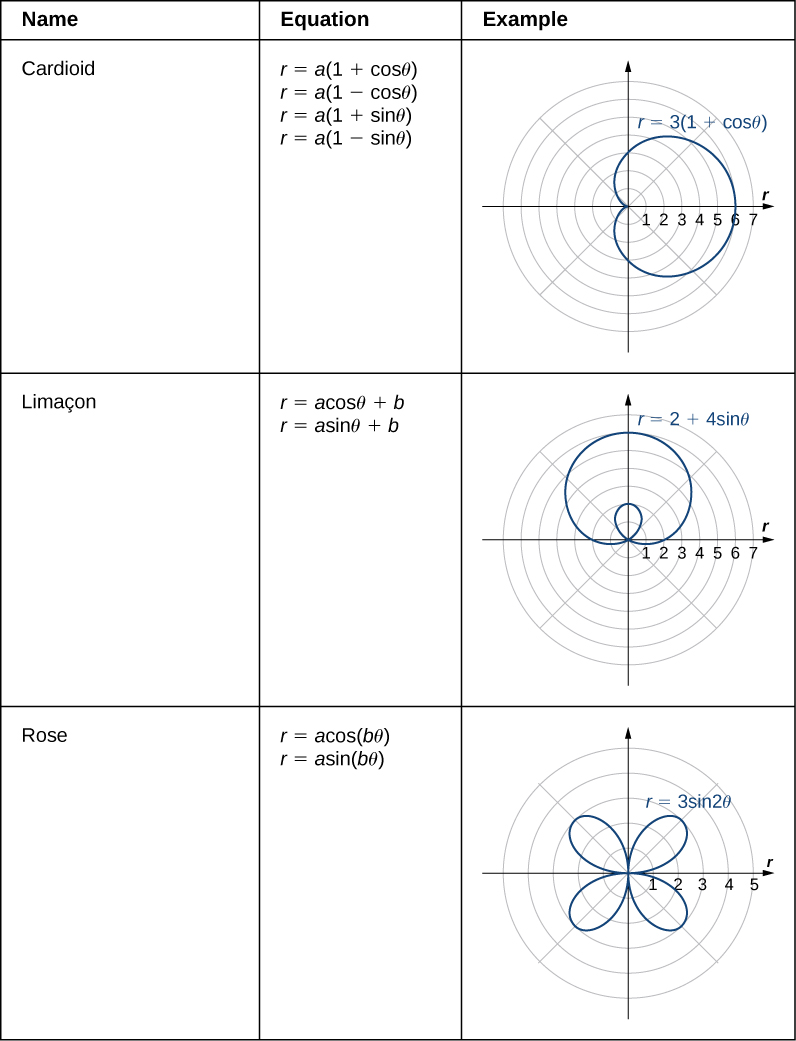

We have now seen several examples of drawing graphs of curves defined by polar equations. A summary of some common curves is given in the tables below. In each equation, a and b are arbitrary constants.

A cardioid is a special case of a limaçon (pronounced “lee-mah-son”), in which

or

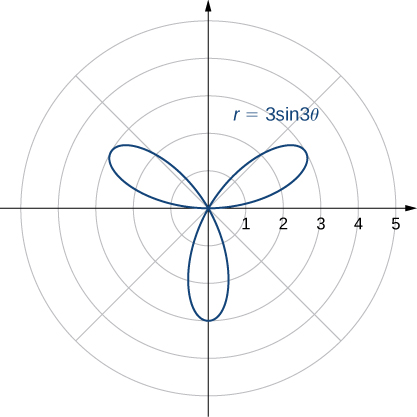

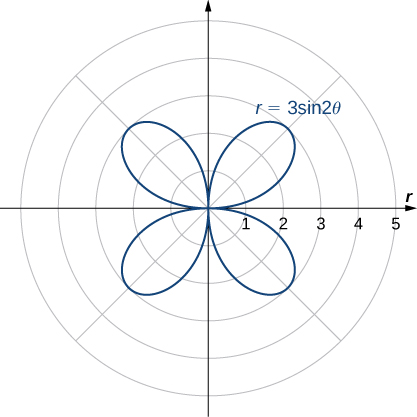

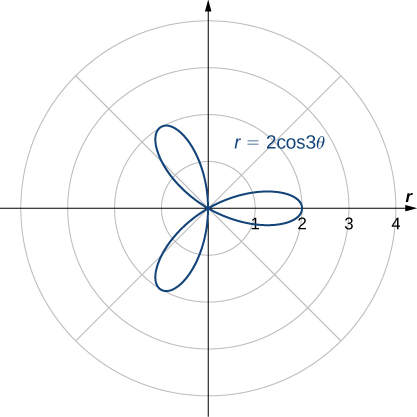

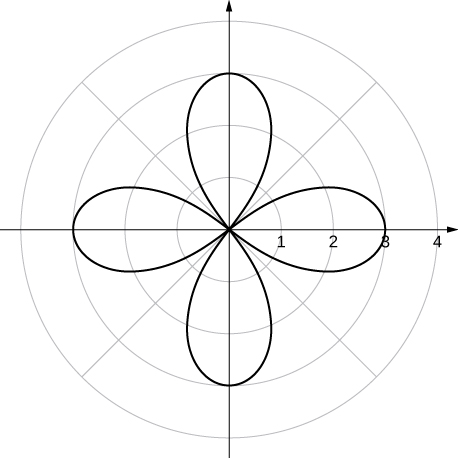

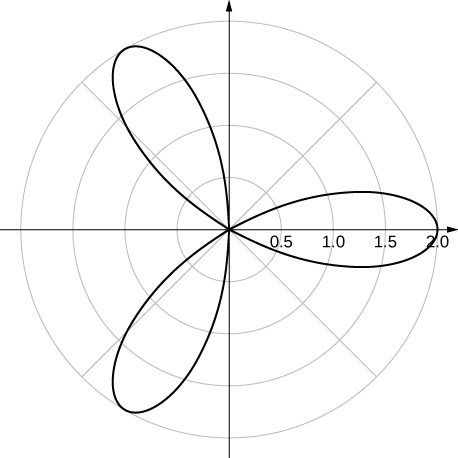

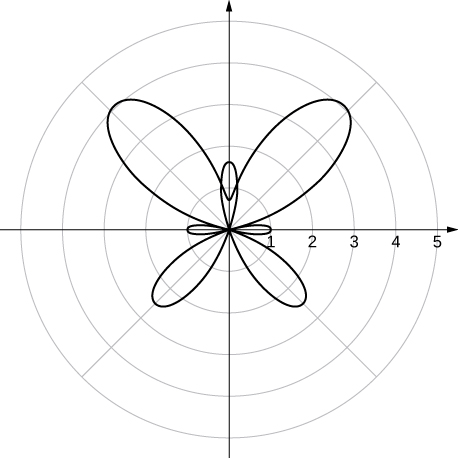

The rose is a very interesting curve. Notice that the graph of

has four petals. However, the graph of

has three petals as shown.

If the coefficient of

is even, the graph has twice as many petals as the coefficient. If the coefficient of

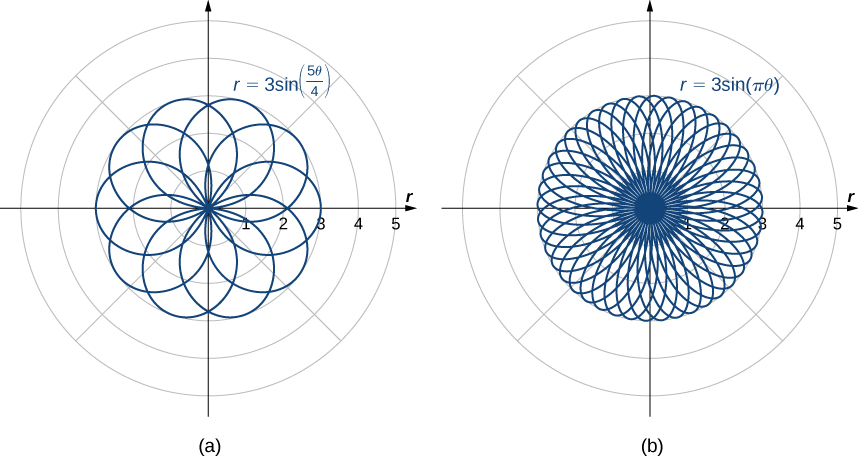

is odd, then the number of petals equals the coefficient. You are encouraged to explore why this happens. Even more interesting graphs emerge when the coefficient of

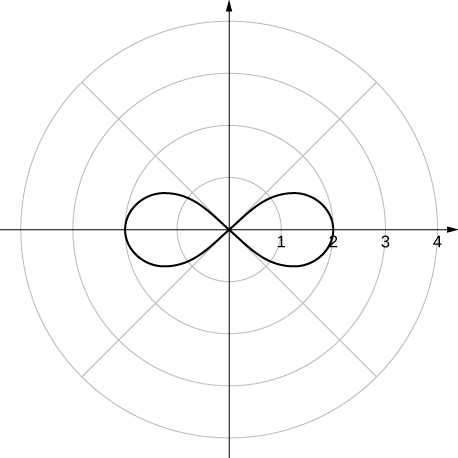

is not an integer. For example, if it is rational, then the curve is closed; that is, it eventually ends where it started ([link](a)). However, if the coefficient is irrational, then the curve never closes ([link](b)). Although it may appear that the curve is closed, a closer examination reveals that the petals just above the positive x axis are slightly thicker. This is because the petal does not quite match up with the starting point.

Since the curve defined by the graph of

never closes, the curve depicted in [link](b) is only a partial depiction. In fact, this is an example of a space-filling curve. A space-filling curve is one that in fact occupies a two-dimensional subset of the real plane. In this case the curve occupies the circle of radius 3 centered at the origin.

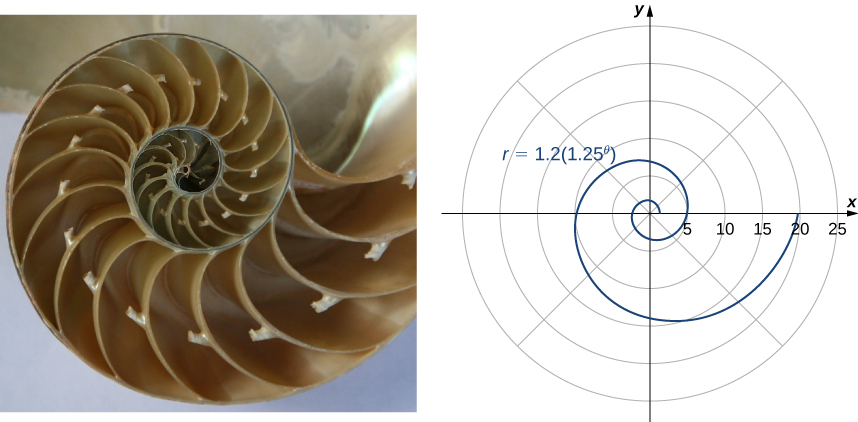

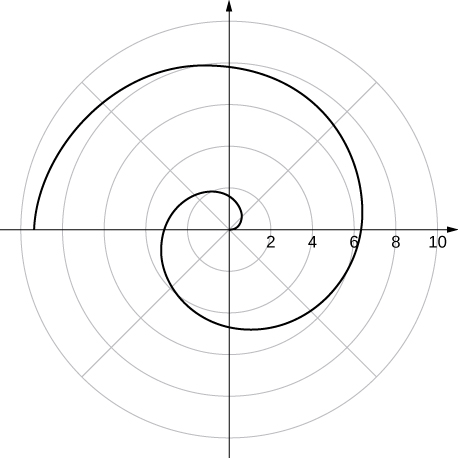

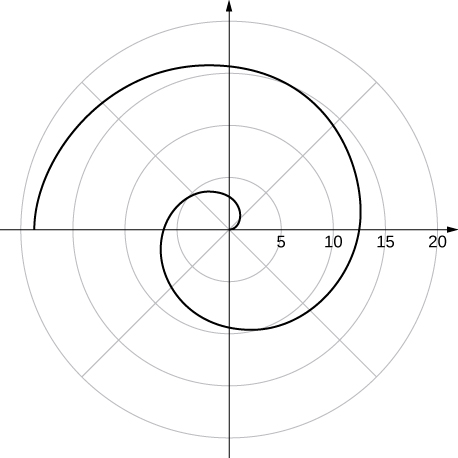

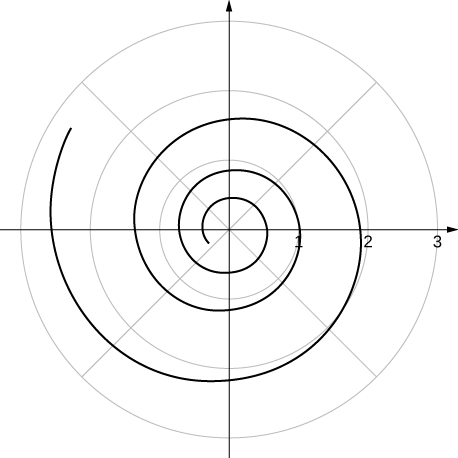

Recall the chambered nautilus introduced in the chapter opener. This creature displays a spiral when half the outer shell is cut away. It is possible to describe a spiral using rectangular coordinates. [link] shows a spiral in rectangular coordinates. How can we describe this curve mathematically?

As the point P travels around the spiral in a counterclockwise direction, its distance d from the origin increases. Assume that the distance d is a constant multiple k of the angle

that the line segment OP makes with the positive x-axis. Therefore

where

is the origin. Now use the distance formula and some trigonometry:

Although this equation describes the spiral, it is not possible to solve it directly for either x or y. However, if we use polar coordinates, the equation becomes much simpler. In particular,

and

is the second coordinate. Therefore the equation for the spiral becomes

Note that when

we also have

so the spiral emanates from the origin. We can remove this restriction by adding a constant to the equation. Then the equation for the spiral becomes

for arbitrary constants

and

This is referred to as an Archimedean spiral, after the Greek mathematician Archimedes.

Another type of spiral is the logarithmic spiral, described by the function

A graph of the function

is given in [link]. This spiral describes the shell shape of the chambered nautilus.

Suppose a curve is described in the polar coordinate system via the function

Since we have conversion formulas from polar to rectangular coordinates given by

it is possible to rewrite these formulas using the function

This step gives a parameterization of the curve in rectangular coordinates using

as the parameter. For example, the spiral formula

from [link] becomes

Letting

range from

to

generates the entire spiral.

When studying symmetry of functions in rectangular coordinates (i.e., in the form

we talk about symmetry with respect to the y-axis and symmetry with respect to the origin. In particular, if

for all

in the domain of

then

is an even function and its graph is symmetric with respect to the y-axis. If

for all

in the domain of

then

is an odd function and its graph is symmetric with respect to the origin. By determining which types of symmetry a graph exhibits, we can learn more about the shape and appearance of the graph. Symmetry can also reveal other properties of the function that generates the graph. Symmetry in polar curves works in a similar fashion.

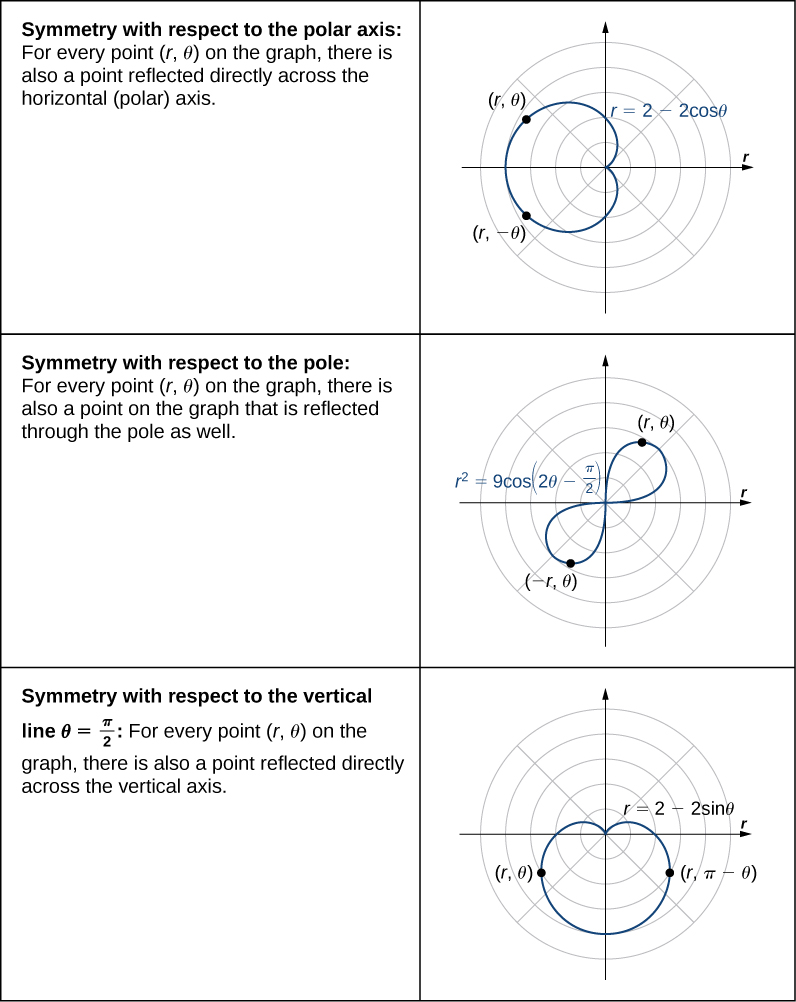

Consider a curve generated by the function

in polar coordinates.

on the graph, the point

is also on the graph. Similarly, the equation

is unchanged by replacing

with

on the graph, the point

is also on the graph. Similarly, the equation

is unchanged when replacing

with

or

with

if for every point

on the graph, the point

is also on the graph. Similarly, the equation

is unchanged when

is replaced by

The following table shows examples of each type of symmetry.

<div data-type="example">

<div data-type="example">

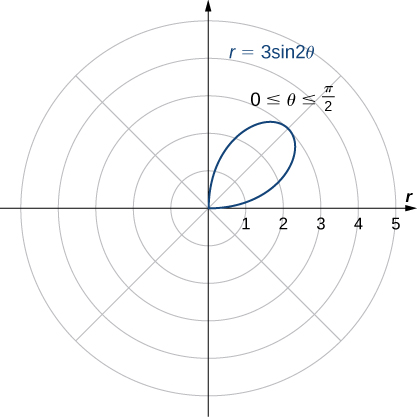

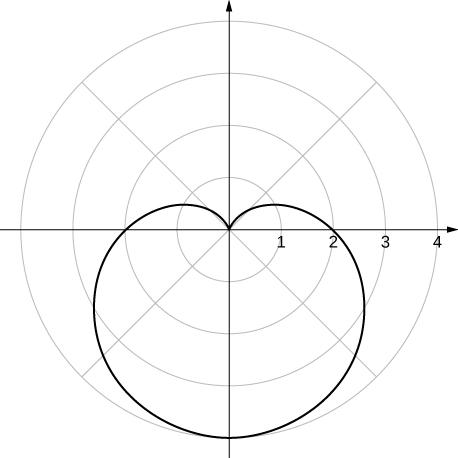

Find the symmetry of the rose defined by the equation

and create a graph.

Suppose the point

is on the graph of

with

This gives

Since this changes the original equation, this test is not satisfied. However, returning to the original equation and replacing

with

and

with

yields

Multiplying both sides of this equation by

gives

which is the original equation. This demonstrates that the graph is symmetric with respect to the polar axis.

with

which yields

Multiplying both sides by −1 gives

which does not agree with the original equation. Therefore the equation does not pass the test for this symmetry. However, returning to the original equation and replacing

with

gives

Since this agrees with the original equation, the graph is symmetric about the pole.

first replace both

with

and

with

Multiplying both sides of this equation by

gives

which is the original equation. Therefore the graph is symmetric about the vertical line

This graph has symmetry with respect to the polar axis, the origin, and the vertical line going through the pole. To graph the function, tabulate values of

between 0 and

and then reflect the resulting graph.

| {: valign=”top”} | ———- |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”} |

| {: valign=”top”}{: .unnumbered summary=”This table has two columns and six rows. The first row is a header row, and it reads from left to right θ and r. Below the header row, in the first column, the values read 0, π/6, π/4, π/3, and π/2. In the second column, the values read 0, (3 times the square root of 3) all divided by 2, which is approximately equal to 2.6, 3, (3 times the square root of 3) all divided by 2, which is approximately equal to 2.6, and 0.” data-label=””}

This gives one petal of the rose, as shown in the following graph.

Reflecting this image into the other three quadrants gives the entire graph as shown.

</div>

Determine the symmetry of the graph determined by the equation

and create a graph.

Symmetric with respect to the polar axis.* * *

Use [link].

and

In the following exercises, plot the point whose polar coordinates are given by first constructing the angle

and then marking off the distance r along the ray.

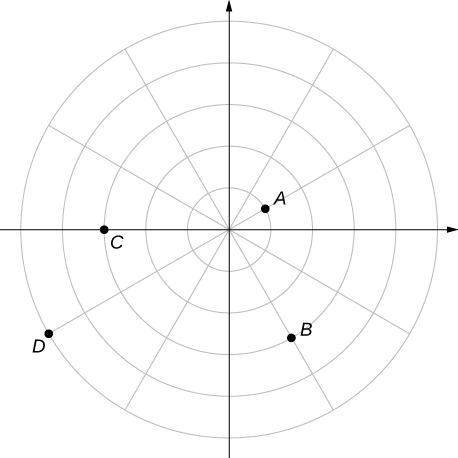

For the following exercises, consider the polar graph below. Give two sets of polar coordinates for each point.

Coordinates of point A.

Coordinates of point B.

Coordinates of point C.

Coordinates of point D.

For the following exercises, the rectangular coordinates of a point are given. Find two sets of polar coordinates for the point in

Round to three decimal places.

(3, −4)

For the following exercises, find rectangular coordinates for the given point in polar coordinates.

For the following exercises, determine whether the graphs of the polar equation are symmetric with respect to the

-axis, the

-axis, or the origin.

Symmetry with respect to the x-axis, y-axis, and origin.

Symmetric with respect to x-axis only.

Symmetry with respect to x-axis only.

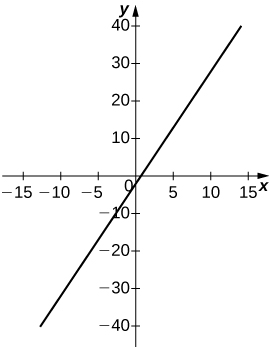

For the following exercises, describe the graph of each polar equation. Confirm each description by converting into a rectangular equation.

Line

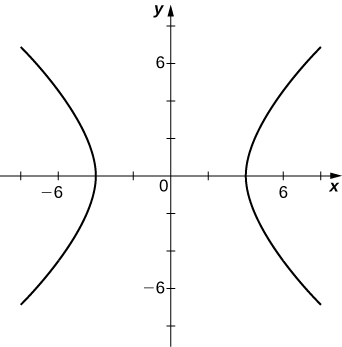

For the following exercises, convert the rectangular equation to polar form and sketch its graph.

Hyperbola; polar form

or

For the following exercises, convert the rectangular equation to polar form and sketch its graph.

For the following exercises, convert the polar equation to rectangular form and sketch its graph.

For the following exercises, sketch a graph of the polar equation and identify any symmetry.

y-axis symmetry

y-axis symmetry

x- and y-axis symmetry and symmetry about the pole

x-axis symmetry

x- and y-axis symmetry and symmetry about the pole

no symmetry

[T] The graph of

is called a strophoid. Use a graphing utility to sketch the graph, and, from the graph, determine the asymptote.

[T] Use a graphing utility and sketch the graph of

a line

[T] Use a graphing utility to graph

[T] Use technology to graph

[T] Use technology to plot

(use the interval

Without using technology, sketch the polar curve

[T] Use a graphing utility to plot

for

[T] Use technology to plot

for

[T] There is a curve known as the “Black Hole.” Use technology to plot

for

[T] Use the results of the preceding two problems to explore the graphs of

and

for

Answers vary. One possibility is the spiral lines become closer together and the total number of spirals increases.

the angle formed by a line segment connecting the origin to a point in the polar coordinate system with the positive radial (x) axis, measured counterclockwise

or

or

If

then the graph is a cardioid

the radial coordinate, and

the angular coordinate

the coordinate in the polar coordinate system that measures the distance from a point in the plane to the pole

or

for a positive constant a

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: