In this section, we consider centers of mass (also called centroids, under certain conditions) and moments. The basic idea of the center of mass is the notion of a balancing point. Many of us have seen performers who spin plates on the ends of sticks. The performers try to keep several of them spinning without allowing any of them to drop. If we look at a single plate (without spinning it), there is a sweet spot on the plate where it balances perfectly on the stick. If we put the stick anywhere other than that sweet spot, the plate does not balance and it falls to the ground. (That is why performers spin the plates; the spin helps keep the plates from falling even if the stick is not exactly in the right place.) Mathematically, that sweet spot is called the center of mass of the plate.

In this section, we first examine these concepts in a one-dimensional context, then expand our development to consider centers of mass of two-dimensional regions and symmetry. Last, we use centroids to find the volume of certain solids by applying the theorem of Pappus.

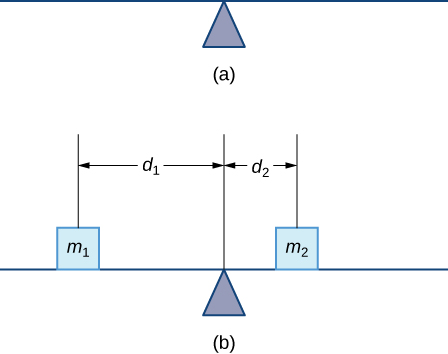

Let’s begin by looking at the center of mass in a one-dimensional context. Consider a long, thin wire or rod of negligible mass resting on a fulcrum, as shown in [link](a). Now suppose we place objects having masses

and

at distances

and

from the fulcrum, respectively, as shown in [link](b).

The most common real-life example of a system like this is a playground seesaw, or teeter-totter, with children of different weights sitting at different distances from the center. On a seesaw, if one child sits at each end, the heavier child sinks down and the lighter child is lifted into the air. If the heavier child slides in toward the center, though, the seesaw balances. Applying this concept to the masses on the rod, we note that the masses balance each other if and only if

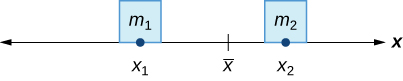

In the seesaw example, we balanced the system by moving the masses (children) with respect to the fulcrum. However, we are really interested in systems in which the masses are not allowed to move, and instead we balance the system by moving the fulcrum. Suppose we have two point masses,

and

located on a number line at points

and

respectively ([link]). The center of mass,

is the point where the fulcrum should be placed to make the system balance.

Thus, we have

The expression in the numerator,

is called the first moment of the system with respect to the origin. If the context is clear, we often drop the word first and just refer to this expression as the moment of the system. The expression in the denominator,

is the total mass of the system. Thus, the center of mass of the system is the point at which the total mass of the system could be concentrated without changing the moment.

This idea is not limited just to two point masses. In general, if n masses,

are placed on a number line at points

respectively, then the center of mass of the system is given by

Let

be point masses placed on a number line at points

respectively, and let

denote the total mass of the system. Then, the moment of the system with respect to the origin is given by

and the center of mass of the system is given by

We apply this theorem in the following example.

Suppose four point masses are placed on a number line as follows:

Find the moment of the system with respect to the origin and find the center of mass of the system.

First, we need to calculate the moment of the system:

Now, to find the center of mass, we need the total mass of the system:

Then we have

The center of mass is located 1/2 m to the left of the origin.

Suppose four point masses are placed on a number line as follows:

Find the moment of the system with respect to the origin and find the center of mass of the system.

Use the process from the previous example.

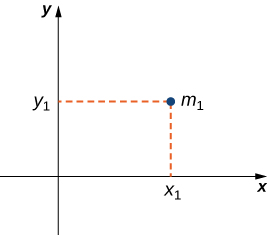

We can generalize this concept to find the center of mass of a system of point masses in a plane. Let

be a point mass located at point

in the plane. Then the moment

of the mass with respect to the x-axis is given by

Similarly, the moment

with respect to the y-axis is given by

Notice that the x-coordinate of the point is used to calculate the moment with respect to the y-axis, and vice versa. The reason is that the x-coordinate gives the distance from the point mass to the y-axis, and the y-coordinate gives the distance to the x-axis (see the following figure).

If we have several point masses in the xy-plane, we can use the moments with respect to the x- and y-axes to calculate the x- and y-coordinates of the center of mass of the system.

Let

be point masses located in the xy-plane at points

respectively, and let

denote the total mass of the system. Then the moments

and

of the system with respect to the x- and y-axes, respectively, are given by

Also, the coordinates of the center of mass

of the system are

The next example demonstrates how to apply this theorem.

Suppose three point masses are placed in the xy-plane as follows (assume coordinates are given in meters):

Find the center of mass of the system.

First we calculate the total mass of the system:

Next we find the moments with respect to the x- and y-axes:

Then we have

The center of mass of the system is

in meters.

Suppose three point masses are placed on a number line as follows (assume coordinates are given in meters):

Find the center of mass of the system.

m

Use the process from the previous example.

So far we have looked at systems of point masses on a line and in a plane. Now, instead of having the mass of a system concentrated at discrete points, we want to look at systems in which the mass of the system is distributed continuously across a thin sheet of material. For our purposes, we assume the sheet is thin enough that it can be treated as if it is two-dimensional. Such a sheet is called a lamina. Next we develop techniques to find the center of mass of a lamina. In this section, we also assume the density of the lamina is constant.

Laminas are often represented by a two-dimensional region in a plane. The geometric center of such a region is called its centroid. Since we have assumed the density of the lamina is constant, the center of mass of the lamina depends only on the shape of the corresponding region in the plane; it does not depend on the density. In this case, the center of mass of the lamina corresponds to the centroid of the delineated region in the plane. As with systems of point masses, we need to find the total mass of the lamina, as well as the moments of the lamina with respect to the x- and y-axes.

We first consider a lamina in the shape of a rectangle. Recall that the center of mass of a lamina is the point where the lamina balances. For a rectangle, that point is both the horizontal and vertical center of the rectangle. Based on this understanding, it is clear that the center of mass of a rectangular lamina is the point where the diagonals intersect, which is a result of the symmetry principle, and it is stated here without proof.

If a region R is symmetric about a line l, then the centroid of R lies on l.

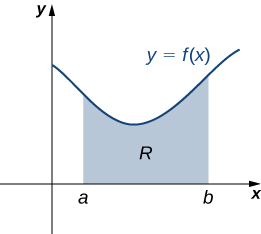

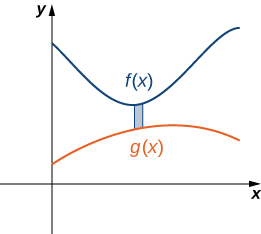

Let’s turn to more general laminas. Suppose we have a lamina bounded above by the graph of a continuous function

below by the x-axis, and on the left and right by the lines

and

respectively, as shown in the following figure.

As with systems of point masses, to find the center of mass of the lamina, we need to find the total mass of the lamina, as well as the moments of the lamina with respect to the x- and y-axes. As we have done many times before, we approximate these quantities by partitioning the interval

and constructing rectangles.

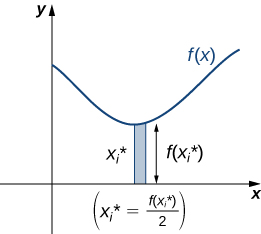

For

let

be a regular partition of

Recall that we can choose any point within the interval

as our

In this case, we want

to be the x-coordinate of the centroid of our rectangles. Thus, for

we select

such that

is the midpoint of the interval. That is,

Now, for

construct a rectangle of height

on

The center of mass of this rectangle is

as shown in the following figure.

Next, we need to find the total mass of the rectangle. Let

represent the density of the lamina (note that

is a constant). In this case,

is expressed in terms of mass per unit area. Thus, to find the total mass of the rectangle, we multiply the area of the rectangle by

Then, the mass of the rectangle is given by

To get the approximate mass of the lamina, we add the masses of all the rectangles to get

This is a Riemann sum. Taking the limit as

gives the exact mass of the lamina:

Next, we calculate the moment of the lamina with respect to the x-axis. Returning to the representative rectangle, recall its center of mass is

Recall also that treating the rectangle as if it is a point mass located at the center of mass does not change the moment. Thus, the moment of the rectangle with respect to the x-axis is given by the mass of the rectangle,

multiplied by the distance from the center of mass to the x-axis:

Therefore, the moment with respect to the x-axis of the rectangle is

Adding the moments of the rectangles and taking the limit of the resulting Riemann sum, we see that the moment of the lamina with respect to the x-axis is

We derive the moment with respect to the y-axis similarly, noting that the distance from the center of mass of the rectangle to the y-axis is

Then the moment of the lamina with respect to the y-axis is given by

We find the coordinates of the center of mass by dividing the moments by the total mass to give

If we look closely at the expressions for

we notice that the constant

cancels out when

and

are calculated.

We summarize these findings in the following theorem.

Let R denote a region bounded above by the graph of a continuous function

below by the x-axis, and on the left and right by the lines

and

respectively. Let

denote the density of the associated lamina. Then we can make the following statements:

and

of the lamina with respect to the x- and y-axes, respectively, are

are

In the next example, we use this theorem to find the center of mass of a lamina.

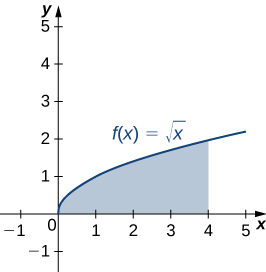

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by the x-axis over the interval

Find the centroid of the region.

The region is depicted in the following figure.

Since we are only asked for the centroid of the region, rather than the mass or moments of the associated lamina, we know the density constant

cancels out of the calculations eventually. Therefore, for the sake of convenience, let’s assume

First, we need to calculate the total mass:

Next, we compute the moments:

and

Thus, we have

The centroid of the region is

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by the x-axis over the interval

Find the centroid of the region.

The centroid of the region is

Use the process from the previous example.

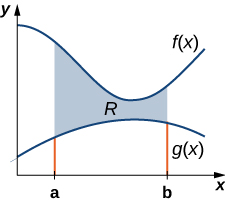

We can adapt this approach to find centroids of more complex regions as well. Suppose our region is bounded above by the graph of a continuous function

as before, but now, instead of having the lower bound for the region be the x-axis, suppose the region is bounded below by the graph of a second continuous function,

as shown in the following figure.

Again, we partition the interval

and construct rectangles. A representative rectangle is shown in the following figure.

Note that the centroid of this rectangle is

We won’t go through all the details of the Riemann sum development, but let’s look at some of the key steps. In the development of the formulas for the mass of the lamina and the moment with respect to the y-axis, the height of each rectangle is given by

which leads to the expression

in the integrands.

In the development of the formula for the moment with respect to the x-axis, the moment of each rectangle is found by multiplying the area of the rectangle,

by the distance of the centroid from the x-axis,

which gives

Summarizing these findings, we arrive at the following theorem.

Let R denote a region bounded above by the graph of a continuous function

below by the graph of the continuous function

and on the left and right by the lines

and

respectively. Let

denote the density of the associated lamina. Then we can make the following statements:

and

of the lamina with respect to the x- and y-axes, respectively, are

are

We illustrate this theorem in the following example.

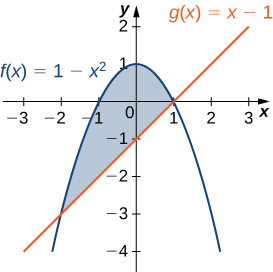

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by the graph of the function

Find the centroid of the region.

The region is depicted in the following figure.

The graphs of the functions intersect at

and

so we integrate from −2 to 1. Once again, for the sake of convenience, assume

First, we need to calculate the total mass:

Next, we compute the moments:

and

Therefore, we have

The centroid of the region is

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by the graph of the function

Find the centroid of the region.

The centroid of the region is

Use the process from the previous example.

We stated the symmetry principle earlier, when we were looking at the centroid of a rectangle. The symmetry principle can be a great help when finding centroids of regions that are symmetric. Consider the following example.

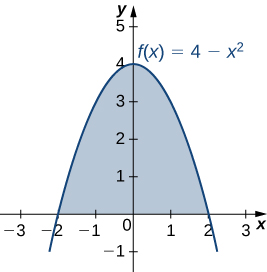

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by the x-axis. Find the centroid of the region.

The region is depicted in the following figure.

The region is symmetric with respect to the y-axis. Therefore, the x-coordinate of the centroid is zero. We need only calculate

Once again, for the sake of convenience, assume

First, we calculate the total mass:

Next, we calculate the moments. We only need

Then we have

The centroid of the region is

Let R be the region bounded above by the graph of the function

and below by x-axis. Find the centroid of the region.

The centroid of the region is

Use the process from the previous example.

The Grand Canyon Skywalk opened to the public on March 28, 2007. This engineering marvel is a horseshoe-shaped observation platform suspended 4000 ft above the Colorado River on the West Rim of the Grand Canyon. Its crystal-clear glass floor allows stunning views of the canyon below (see the following figure).

The Skywalk is a cantilever design, meaning that the observation platform extends over the rim of the canyon, with no visible means of support below it. Despite the lack of visible support posts or struts, cantilever structures are engineered to be very stable and the Skywalk is no exception. The observation platform is attached firmly to support posts that extend 46 ft down into bedrock. The structure was built to withstand 100-mph winds and an 8.0-magnitude earthquake within 50 mi, and is capable of supporting more than 70,000,000 lb.

One factor affecting the stability of the Skywalk is the center of gravity of the structure. We are going to calculate the center of gravity of the Skywalk, and examine how the center of gravity changes when tourists walk out onto the observation platform.

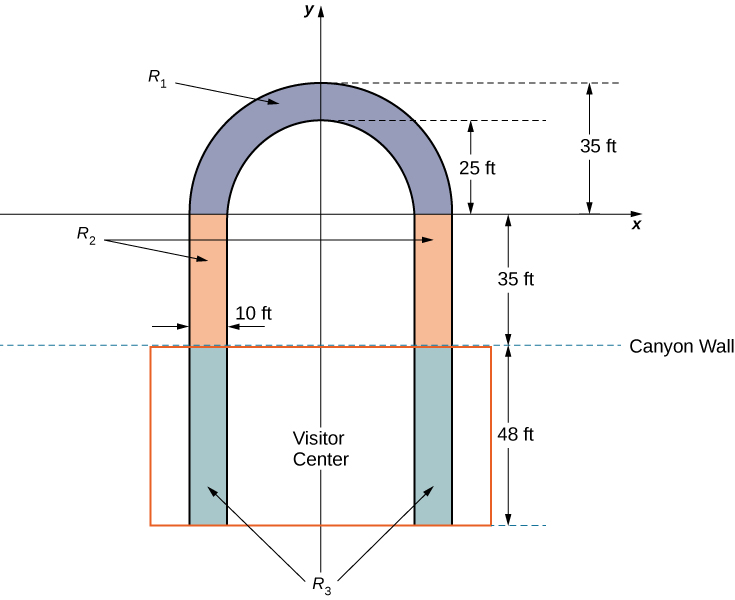

The observation platform is U-shaped. The legs of the U are 10 ft wide and begin on land, under the visitors’ center, 48 ft from the edge of the canyon. The platform extends 70 ft over the edge of the canyon.

To calculate the center of mass of the structure, we treat it as a lamina and use a two-dimensional region in the xy-plane to represent the platform. We begin by dividing the region into three subregions so we can consider each subregion separately. The first region, denoted

consists of the curved part of the U. We model

as a semicircular annulus, with inner radius 25 ft and outer radius 35 ft, centered at the origin (see the following figure).

The legs of the platform, extending 35 ft between

and the canyon wall, comprise the second sub-region,

Last, the ends of the legs, which extend 48 ft under the visitor center, comprise the third sub-region,

Assume the density of the lamina is constant and assume the total weight of the platform is 1,200,000 lb (not including the weight of the visitor center; we will consider that later). Use

and

should include the areas of the legs only, not the open space between them. Round answers to the nearest square foot.

Treating the visitor center as a point mass, recalculate the center of mass of the system. How does the center of mass change?

This section ends with a discussion of the theorem of Pappus for volume, which allows us to find the volume of particular kinds of solids by using the centroid. (There is also a theorem of Pappus for surface area, but it is much less useful than the theorem for volume.)

Let R be a region in the plane and let l be a line in the plane that does not intersect R. Then the volume of the solid of revolution formed by revolving R around l is equal to the area of R multiplied by the distance d traveled by the centroid of R.

We can prove the case when the region is bounded above by the graph of a function

and below by the graph of a function

over an interval

and for which the axis of revolution is the y-axis. In this case, the area of the region is

Since the axis of rotation is the y-axis, the distance traveled by the centroid of the region depends only on the x-coordinate of the centroid,

which is

where

Then,

and thus

However, using the method of cylindrical shells, we have

So,

and the proof is complete.

□

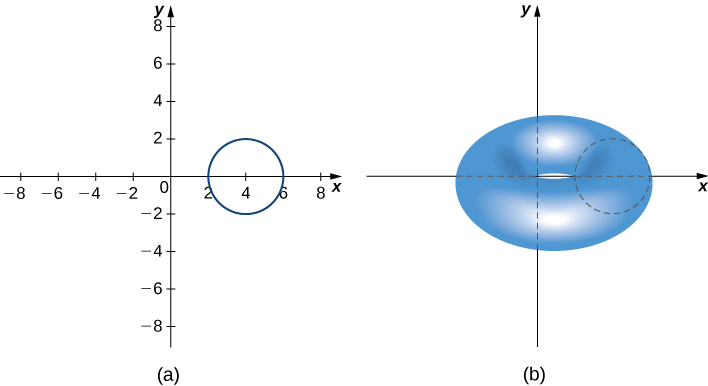

Let R be a circle of radius 2 centered at

Use the theorem of Pappus for volume to find the volume of the torus generated by revolving R around the y-axis.

The region and torus are depicted in the following figure.

The region R is a circle of radius 2, so the area of R is

units2. By the symmetry principle, the centroid of R is the center of the circle. The centroid travels around the y-axis in a circular path of radius 4, so the centroid travels

units. Then, the volume of the torus is

units3.

Let R be a circle of radius 1 centered at

Use the theorem of Pappus for volume to find the volume of the torus generated by revolving R around the y-axis.

units3

Use the process from the previous example.

For point masses distributed in a plane, the moments of the system with respect to the x- and y-axes, respectively, are

and

respectively.

the moments of the system with respect to the x- and y-axes, respectively, are

and

For the following exercises, calculate the center of mass for the collection of masses given.

at

and

at

at

and

at

at

Unit masses at

at

and

at

at

and

at

For the following exercises, compute the center of mass

for

for

for

and

for

for

for

for

for

for

for

for

For the following exercises, compute the center of mass

Use symmetry to help locate the center of mass whenever possible.

in the square

in the triangle with vertices

and

for the region bounded by

and

For the following exercises, use a calculator to draw the region, then compute the center of mass

Use symmetry to help locate the center of mass whenever possible.

[T] The region bounded by

and

[T] The region between

and

[T] The region between

and

[T] Region between

and

[T] The region bounded by

[T] The region bounded by

and

[T] The region bounded by

and

in the first quadrant

For the following exercises, use the theorem of Pappus to determine the volume of the shape.

Rotating

around the

-axis between

and

Rotating

around the

-axis between

and

A general cone created by rotating a triangle with vertices

and

around the

-axis. Does your answer agree with the volume of a cone?

A general cylinder created by rotating a rectangle with vertices

and

around the

-axis. Does your answer agree with the volume of a cylinder?

A sphere created by rotating a semicircle with radius

around the

-axis. Does your answer agree with the volume of a sphere?

For the following exercises, use a calculator to draw the region enclosed by the curve. Find the area

and the centroid

for the given shapes. Use symmetry to help locate the center of mass whenever possible.

[T] Quarter-circle:

and

[T] Triangle:

and

[T] Lens:

and

[T] Ring:

and

[T] Half-ring:

and

Find the generalized center of mass in the sliver between

and

with

Then, use the Pappus theorem to find the volume of the solid generated when revolving around the y-axis.

Find the generalized center of mass between

and

Then, use the Pappus theorem to find the volume of the solid generated when revolving around the y-axis.

Center of mass:

volume:

Find the generalized center of mass between

and

Then, use the Pappus theorem to find the volume of the solid generated when revolving around the y-axis.

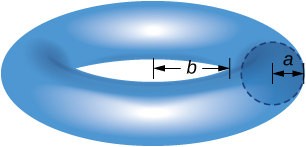

Use the theorem of Pappus to find the volume of a torus (pictured here). Assume that a disk of radius

is positioned with the left end of the circle at

and is rotated around the y-axis.

Volume:

Find the center of mass

for a thin wire along the semicircle

with unit mass. (Hint: Use the theorem of Pappus.)

if, instead, we consider a region in the plane, bounded above by a function

over an interval

then the moments of the region with respect to the x- and y-axes are given by

and

respectively

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9a1df55a-b167-4736-b5ad-15d996704270@5.1

Attribution: