By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Information about stellar populations holds vital clues to how our Galaxy was built up over time. The flattened disk shape of the Galaxy suggests that it formed through a process similar to the one that leads to the formation of a protostar (see The Birth of Stars and the Discovery of Planets outside the Solar System). Building on this idea, astronomers first developed models that assumed the Galaxy formed from a single rotating cloud. But, as we shall see, this turns out to be only part of the story.

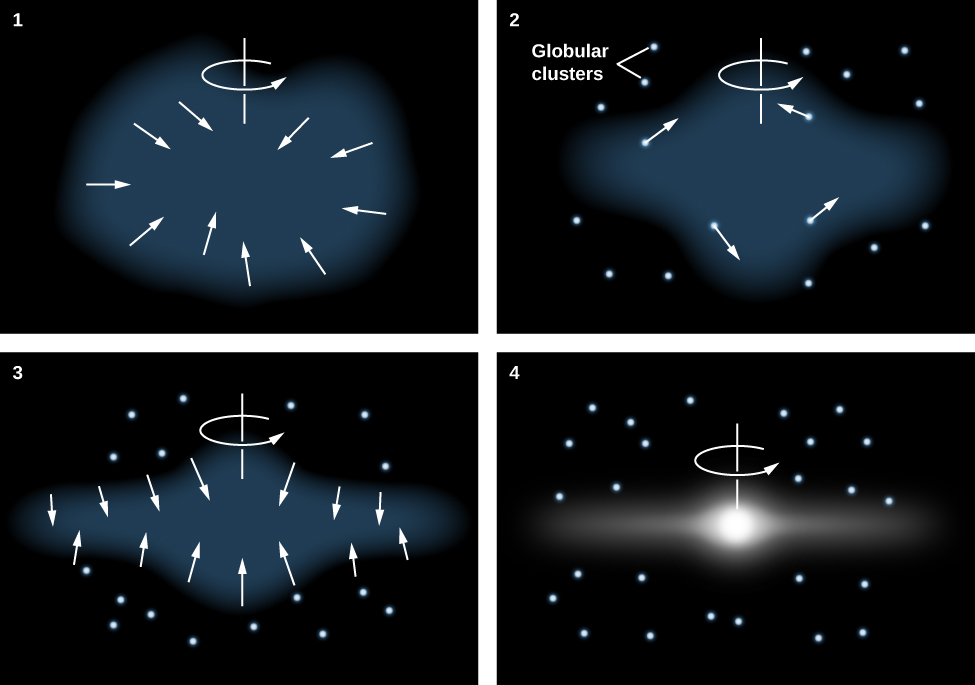

Because the oldest stars—those in the halo and in globular clusters—are distributed in a sphere centered on the nucleus of the Galaxy, it makes sense to assume that the protogalactic cloud that gave birth to our Galaxy was roughly spherical. The oldest stars in the halo have ages of 12 to 13 billion years, so we estimate that the formation of the Galaxy began about that long ago. (See the chapter on The Big Bang for other evidence that galaxies in general began forming a little more than 13 billion years ago.) Then, just as in the case of star formation, the protogalactic cloud collapsed and formed a thin rotating disk. Stars born before the cloud collapsed did not participate in the collapse, but have continued to orbit in the halo to the present day ([link]).

Gravitational forces caused the gas in the thin disk to fragment into clouds or clumps with masses like those of star clusters. These individual clouds then fragmented further to form stars. Since the oldest stars in the disk are nearly as old as the youngest stars in the halo, the collapse must have been rapid (astronomically speaking), requiring perhaps no more than a few hundred million years.

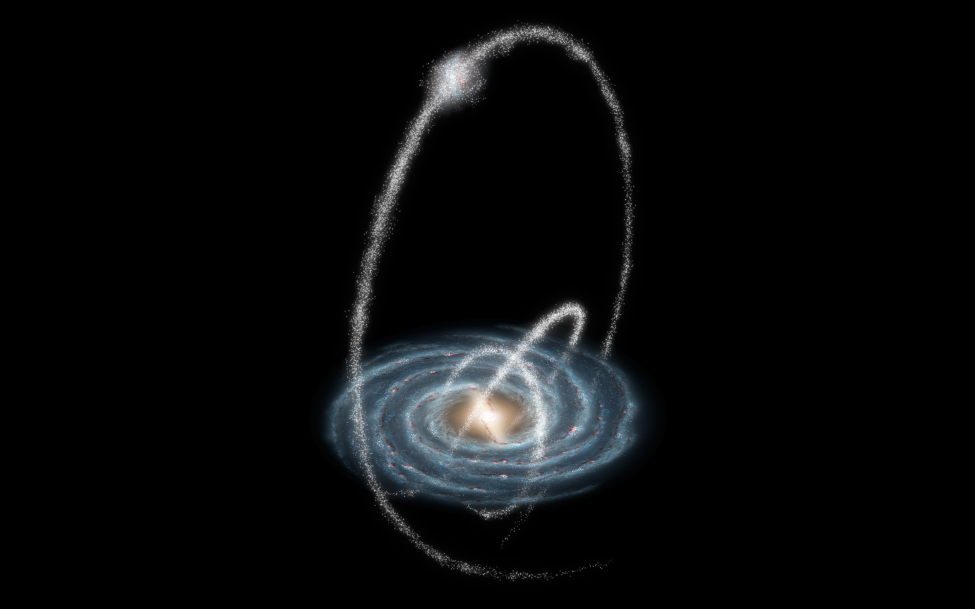

In past decades, astronomers have learned that the evolution of the Galaxy has not been quite as peaceful as this monolithic collapse model suggests. In 1994, astronomers discovered a small new galaxy in the direction of the constellation of Sagittarius. The Sagittarius dwarf galaxy is currently about 70,000 light-years away from Earth and 50,000 light-years from the center of the Galaxy. It is the closest galaxy known ([link]). It is very elongated, and its shape indicates that it is being torn apart by our Galaxy’s gravitational tides—just as Comet Shoemaker-Levy 9 was torn apart when it passed too close to Jupiter in 1992.

The Sagittarius galaxy is much smaller than the Milky Way and is about 10,000 times less massive than our Galaxy. All of the stars in the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy seem destined to end up in the bulge and halo of the Milky Way. But don’t sound the funeral bells for the little galaxy quite yet; the ingestion of the Sagittarius dwarf will take another 100 million years or so, and the stars themselves will survive.

![In 1994, British astronomers discovered a galaxy in the constellation of Sagittarius, located only about 50,000 light-years from the center of the Milky Way and falling into our Galaxy. This image covers a region approximately 70° × 50° and combines a black-and-white view of the disk of our Galaxy with a red contour map showing the brightness of the dwarf galaxy. The dwarf galaxy lies on the other side of the galactic center from us. The white stars in the red region mark the locations of several globular clusters contained within the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy. The cross marks the galactic center. The horizontal line corresponds to the galactic plane. The blue outline on either side of the galactic plane corresponds to the infrared image in [link]. The boxes mark regions where detailed studies of individual stars led to the discovery of this galaxy. (credit: modification of work by R. Ibata (UBC), R. Wyse (JHU), R. Sword (IoA)) Sagittarius Dwarf Galaxy. Superimposed on this greyscale image of the galactic center a contour map of the dwarf galaxy is drawn in red above and slightly to the right of center. The white stars in the contour map mark the locations of several globular clusters contained within the dwarf galaxy. The cross marks the center of the Milky Way. The horizontal line corresponds to the galactic plane. The blue outline on either side of the galactic plane corresponds to Herschel’s diagram of the Milky Way. The boxes mark regions where detailed studies of individual stars led to the discovery of this galaxy.](../resources/OSC_Astro_25_06_Dwarf.jpg)

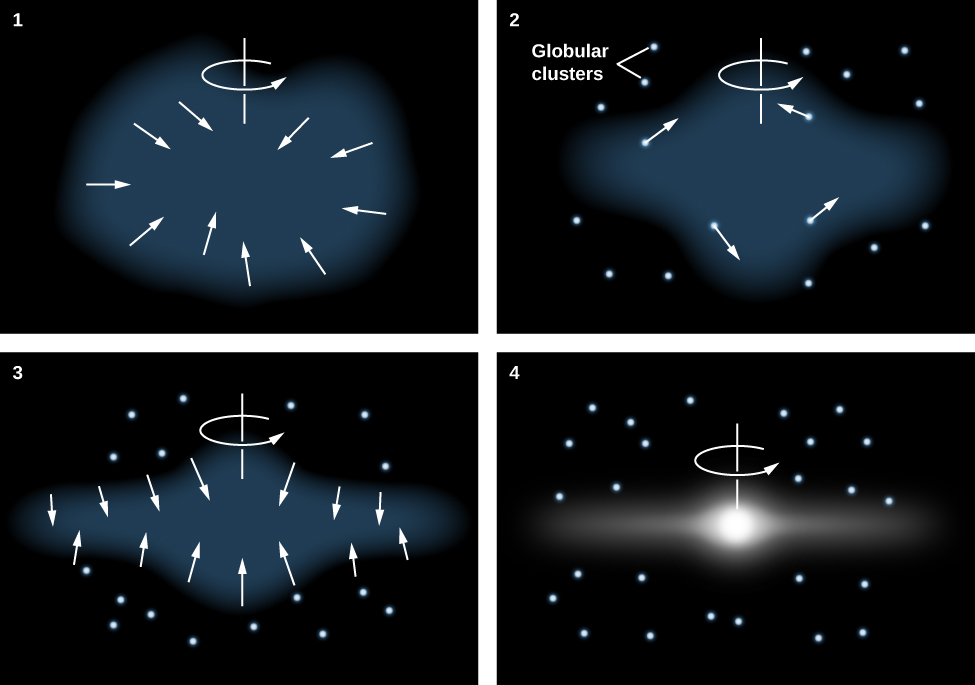

Since that discovery, evidence has been found for many more close encounters between our Galaxy and other neighbor galaxies. When a small galaxy ventures too close, the force of gravity exerted by our Galaxy tugs harder on the near side than on the far side. The net effect is that the stars that originally belonged to the small galaxy are spread out into a long stream that orbits through the halo of the Milky Way ([link]).

Such a tidal stream can maintain its identity for billions of years. To date, astronomers have now identified streams originating from 12 small galaxies that ventured too close to the much larger Milky Way. Six more streams are associated with globular clusters. It has been suggested that large globular clusters, like Omega Centauri, are actually dense nuclei of cannibalized dwarf galaxies. The globular cluster M54 is now thought to be the nucleus of the Sagittarius dwarf we discussed earlier, which is currently merging with the Milky Way ([link]). The stars in the outer regions of such galaxies are stripped off by the gravitational pull of the Milky Way, but the central dense regions may survive.

Calculations indicate that the Galaxy’s thick disk may be a product of one or more such collisions with other galaxies. Accretion of a satellite galaxy would stir up the orbits of the stars and gas clouds originally in the thin disk and cause them to move higher above and below the mid-plane of the Galaxy. Meanwhile, the Galaxy’s stars would add to the fluffed-up mix. If such a collision happened about 10 billion years ago, then any gas in the two galaxies that had not yet formed into stars would have had plenty of time to settle back down into the thin disk. The gas could then have begun forming subsequent generations of population I stars. This timing is also consistent with the typical ages of stars in the thick disk.

The Milky Way has more collisions in store. An example is the Canis Major dwarf galaxy, which has a mass of about 1% of the mass of the Milky Way. Already long tidal tails have been stripped from this galaxy, which have wrapped themselves around the Milky Way three times. Several of the globular clusters found in the Milky Way may also have come from the Canis Major dwarf, which is expected to merge gradually with the Milky Way over about the next billion years.

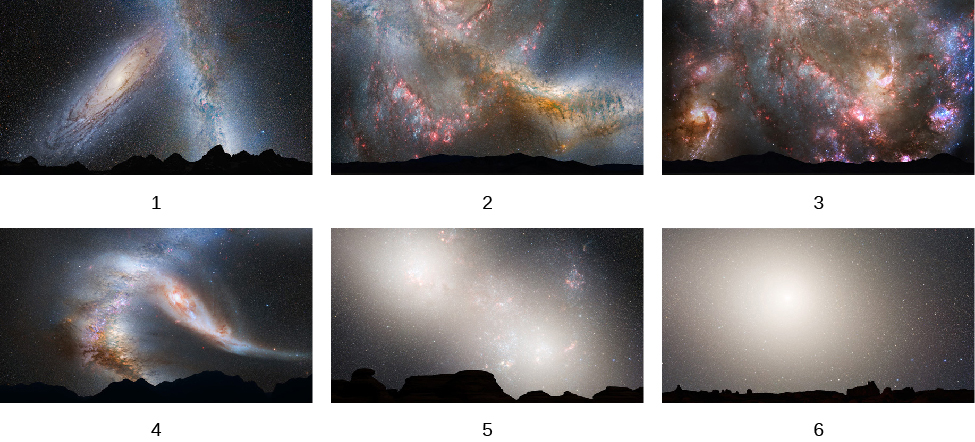

In about 3 billion years, the Milky Way itself will be swallowed up, since it and the Andromeda galaxy are on a collision course. Our computer models show that after a complex interaction, the two will merge to form a larger, more rounded galaxy ([link]).

We are thus coming to realize that “environmental influences” (and not just a galaxy’s original characteristics) play an important role in determining the properties and development of our Galaxy. In future chapters we will see that collisions and mergers are a major factor in the evolution of many other galaxies as well.

The Galaxy began forming a little more than 13 billion years ago. Models suggest that the stars in the halo and globular clusters formed first, while the Galaxy was spherical. The gas, somewhat enriched in heavy elements by the first generation of stars, then collapsed from a spherical distribution to a rotating disk-shaped distribution. Stars are still forming today from the gas and dust that remain in the disk. Star formation occurs most rapidly in the spiral arms, where the density of interstellar matter is highest. The Galaxy captured (and still is capturing) additional stars and globular clusters from small galaxies that ventured too close to the Milky Way. In 3 to 4 billion years, the Galaxy will begin to collide with the Andromeda galaxy, and after about 7 billion years, the two galaxies will merge to form a giant elliptical galaxy.

Blitz, L. “The Dark Side of the Milky Way.” Scientific American (October 2011): 36–43. How we find dark matter and what it tells us about our Galaxy, its warped disk, and its satellite galaxies.

Dvorak, J. “Journey to the Heart of the Milky Way.” Astronomy (February 2008): 28. Measuring nearby stars to determine the properties of the black hole at the center.

Gallagher, J., Wyse, R., & Benjamin, R. “The New Milky Way.” Astronomy (September 2011): 26. Highlights all aspects of the Milky Way based on recent observations.

Goldstein, A. “Finding our Place in the Milky Way.” Astronomy (August 2015): 50. On the history of observations that pinpointed the Sun’s location in the Galaxy.

Haggard, D., & Bower, G. “In the Heart of the Milky Way.” Sky & Telescope (February 2016): 16. On observations of the Galaxy’s nucleus and the supermassive black hole and magnetar there.

Ibata, R., & Gibson, B. “The Ghosts of Galaxies Past.” Scientific American (April 2007): 40. About star streams in the Galaxy that are evidence of past mergers and collisions.

Irion, R. “A Crushing End for Our Galaxy.” Science (January 7, 2000): 62. On the role of mergers in the evolution of the Milky Way.

Irion, R. “Homing in on Black Holes.” Smithsonian (April 2008). On how astronomers probe the large black hole at the center of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Kruesi, L. “How We Mapped the Milky Way.” Astronomy (October 2009): 28.

Kruesi, L. “What Lurks in the Monstrous Heart of the Milky Way?” Astronomy (October 2015): 30. On the center of the Galaxy and the black hole there.

Laughlin, G., & Adams, F. “Celebrating the Galactic Millennium.” Astronomy (November 2001): 39. The long-term future of the Milky Way in the next 90 billion years.

Loeb, A., & Cox, T.J. “Our Galaxy’s Date with Destruction.” Astronomy (June 2008): 28. Describes the upcoming merger of Milky Way and Andromeda.

Szpir, M. “Passing the Bar Exam.” Astronomy (March 1999): 46. On evidence that our Galaxy is a barred spiral.

Tanner, A. “A Trip to the Galactic Center.” Sky & Telescope (April 2003): 44. Nice introduction, with observations pointing to the presence of a black hole.

Trimble, V., & Parker, S. “Meet the Milky Way.” Sky & Telescope (January 1995): 26. Overview of our Galaxy.

Wakker, B., & Richter, P. “Our Growing, Breathing Galaxy.” Scientific American (January 2004): 38. Evidence that our Galaxy is still being built up by the addition of gas and smaller neighbors.

Waller, W. “Redesigning the Milky Way.” Sky & Telescope (September 2004): 50. On recent multi-wavelength surveys of the Galaxy.

Whitt, K. “The Milky Way from the Inside.” Astronomy (November 2001): 58. Fantastic panorama image of the Galaxy, with finder charts and explanations.

International Dark Sky Sanctuaries: http://darksky.org/idsp/sanctuaries/. A listing of dark-sky sanctuaries, parks, and reserves.

Multiwavelength Milky Way: http://mwmw.gsfc.nasa.gov/mmw\_sci.html. This NASA site shows the plane of our Galaxy in a variety of wavelength bands, and includes background material and other resources.

Shapley-Curtis Debate in 1920: http://apod.nasa.gov/diamond\_jubilee/debate\_1920.html. In 1920, astronomers Harlow Shapley and Heber Curtis engaged in a historic debate about how large our Galaxy was and whether other galaxies existed. Here you can find historical and educational material about the debate.

UCLA Galactic Center Group: http://www.galacticcenter.astro.ucla.edu/. Learn more about the work of Andrea Ghez and colleagues on the central region of the Milky Way Galaxy.

Crash of the Titans: http://www.spacetelescope.org/videos/hubblecast55a/. This Hubblecast from 2012 features Jay Anderson and Roeland van der Marel explaining how Andromeda will collide with the Milky Way in the distant future (5:07).

Diner at the Center of the Galaxy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UP7ig8Gxftw. A short discussion from NASA ScienceCast of NuSTAR observations of flares from our Galaxy’s central black hole (3:23).

Hunt for a Supermassive Black Hole: https://www.ted.com/talks/andrea\_ghez\_the\_hunt\_for\_a\_supermassive\_black\_hole. 2009 TED talk by Andrea Ghez on searching for supermassive black holes, particularly the one at the center of the Milky Way (16:19).

Journey to the Galactic Center: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=36xZsgZ0oSo. A brief silent trip into the cluster of stars near the galactic center showing their motions around the center (3:00).

Explain why we see the Milky Way as a faint band of light stretching across the sky.

Explain where in a spiral galaxy you would expect to find globular clusters, molecular clouds, and atomic hydrogen.

Describe several characteristics that distinguish population I stars from population II stars.

Briefly describe the main parts of our Galaxy.

Describe the evidence indicating that a black hole may be at the center of our Galaxy.

Explain why the abundances of heavy elements in stars correlate with their positions in the Galaxy.

What will be the long-term future of our Galaxy?

Suppose the Milky Way was a band of light extending only halfway around the sky (that is, in a semicircle). What, then, would you conclude about the Sun’s location in the Galaxy? Give your reasoning.

Suppose somebody proposed that rather than invoking dark matter to explain the increased orbital velocities of stars beyond the Sun’s orbit, the problem could be solved by assuming that the Milky Way’s central black hole was much more massive. Does simply increasing the assumed mass of the Milky Way’s central supermassive black hole correctly resolve the issue of unexpectedly high orbital velocities in the Galaxy? Why or why not?

The globular clusters revolve around the Galaxy in highly elliptical orbits. Where would you expect the clusters to spend most of their time? (Think of Kepler’s laws.) At any given time, would you expect most globular clusters to be moving at high or low speeds with respect to the center of the Galaxy? Why?

Shapley used the positions of globular clusters to determine the location of the galactic center. Could he have used open clusters? Why or why not?

Consider the following five kinds of objects: open cluster, giant molecular cloud, globular cluster, group of O and B stars, and planetary nebulae.

The dwarf galaxy in Sagittarius is the one closest to the Milky Way, yet it was discovered only in 1994. Can you think of a reason it was not discovered earlier? (Hint: Think about what else is in its constellation.)

Suppose three stars lie in the disk of the Galaxy at distances of 20,000 light-years, 25,000 light-years, and 30,000 light-years from the galactic center, and suppose that right now all three are lined up in such a way that it is possible to draw a straight line through them and on to the center of the Galaxy. How will the relative positions of these three stars change with time? Assume that their orbits are all circular and lie in the plane of the disk.

Why does star formation occur primarily in the disk of the Galaxy?

Where in the Galaxy would you expect to find Type II supernovae, which are the explosions of massive stars that go through their lives very quickly? Where would you expect to find Type I supernovae, which involve the explosions of white dwarfs?

Suppose that stars evolved without losing mass—that once matter was incorporated into a star, it remained there forever. How would the appearance of the Galaxy be different from what it is now? Would there be population I and population II stars? What other differences would there be?

Assume that the Sun orbits the center of the Galaxy at a speed of 220 km/s and a distance of 26,000 light-years from the center.

The Sun orbits the center of the Galaxy in 225 million years at a distance of 26,000 light-years. Given that

where a is the semimajor axis and P is the orbital period, what is the mass of the Galaxy within the Sun’s orbit?

Suppose the Sun orbited a little farther out, but the mass of the Galaxy inside its orbit remained the same as we calculated in [link]. What would be its period at a distance of 30,000 light-years?

We have said that the Galaxy rotates differentially; that is, stars in the inner parts complete a full 360° orbit around the center of the Galaxy more rapidly than stars farther out. Use Kepler’s third law and the mass we derived in [link] to calculate the period of a star that is only 5000 light-years from the center. Now do the same calculation for a globular cluster at a distance of 50,000 light-years. Suppose the Sun, this star, and the globular cluster all fall on a straight line through the center of the Galaxy. Where will they be relative to each other after the Sun completes one full journey around the center of the Galaxy? (Assume that all the mass in the Galaxy is concentrated at its center.)

If our solar system is 4.6 billion years old, how many galactic years has planet Earth been around?

Suppose the average mass of a star in the Galaxy is one-third of a solar mass. Use the value for the mass of the Galaxy that we calculated in [link], and estimate how many stars are in the Milky Way. Give some reasons it is reasonable to assume that the mass of an average star is less than the mass of the Sun.

The first clue that the Galaxy contains a lot of dark matter was the observation that the orbital velocities of stars did not decreases with increasing distance from the center of the Galaxy. Construct a rotation curve for the solar system by using the orbital velocities of the planets, which can be found in Appendix F. How does this curve differ from the rotation curve for the Galaxy? What does it tell you about where most of the mass in the solar system is concentrated?

The best evidence for a black hole at the center of the Galaxy also comes from the application of Kepler’s third law. Suppose a star at a distance of 20 light-hours from the center of the Galaxy has an orbital speed of 6200 km/s. How much mass must be located inside its orbit?

The next step in deciding whether the object in [link] is a black hole is to estimate the density of this mass. Assume that all of the mass is spread uniformly throughout a sphere with a radius of 20 light-hours. What is the density in kg/km3? (Remember that the volume of a sphere is given by

.) Explain why the density might be even higher than the value you have calculated. How does this density compare with that of the Sun or other objects we have talked about in this book?

Suppose the Sagittarius dwarf galaxy merges completely with the Milky Way and adds 150,000 stars to it. Estimate the percentage change in the mass of the Milky Way. Will this be enough mass to affect the orbit of the Sun around the galactic center? Assume that all of the Sagittarius galaxy’s stars end up in the nuclear bulge of the Milky Way Galaxy and explain your answer.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: