By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Is light actually bent from its straight-line path by the mass of Earth? How can light, which has no mass, be affected by gravity? Einstein preferred to think that it is space and time that are affected by the presence of a large mass; light beams, and everything else that travels through space and time, then find their paths affected. Light always follows the shortest path—but that path may not always be straight. This idea is true for human travel on the curved surface of planet Earth, as well. Say you want to fly from Chicago to Rome. Since an airplane can’t go through the solid body of the Earth, the shortest distance is not a straight line but the arc of a great circle.

To show what Einstein’s insight really means, let’s first consider how we locate an event in space and time. For example, imagine you have to describe to worried school officials the fire that broke out in your room when your roommate tried cooking shish kebabs in the fireplace. You explain that your dorm is at 6400 College Avenue, a street that runs in the left-right direction on a map of your town; you are on the fifth floor, which tells where you are in the up-down direction; and you are the sixth room back from the elevator, which tells where you are in the forward-backward direction. Then you explain that the fire broke out at 6:23 p.m. (but was soon brought under control), which specifies the event in time. Any event in the universe, whether nearby or far away, can be pinpointed using the three dimensions of space and the one dimension of time.

Newton considered space and time to be completely independent, and that continued to be the accepted view until the beginning of the twentieth century. But Einstein showed that there is an intimate connection between space and time, and that only by considering the two together—in what we call spacetime—can we build up a correct picture of the physical world. We examine spacetime a bit more closely in the next subsection.

The gist of Einstein’s general theory is that the presence of matter curves or warps the fabric of spacetime. This curving of spacetime is identified with gravity. When something else—a beam of light, an electron, or the starship Enterprise—enters such a region of distorted spacetime, its path will be different from what it would have been in the absence of the matter. As American physicist John Wheeler summarized it: “Matter tells spacetime how to curve; spacetime tells matter how to move.”

The amount of distortion in spacetime depends on the mass of material that is involved and on how concentrated and compact it is. Terrestrial objects, such as the book you are reading, have far too little mass to introduce any significant distortion. Newton’s view of gravity is just fine for building bridges, skyscrapers, or amusement park rides. General relativity does, however, have some practical applications. The GPS (Global Positioning System) in every smartphone can tell you where you are within 5 to 10 meters only because the effects of general and special relativity on the GPS satellites in orbit around the Earth are taken into account.

Unlike a book or your roommate, stars produce measurable distortions in spacetime. A white dwarf, with its stronger surface gravity, produces more distortion just above its surface than does a red giant with the same mass. So, you see, we are eventually going to talk about collapsing stars again, but not before discussing Einstein’s ideas (and the evidence for them) in more detail.

How can we understand the distortion of spacetime by the presence of some (significant) amount of mass? Let’s try the following analogy. You may have seen maps of New York City that squeeze the full three dimensions of this towering metropolis onto a flat sheet of paper and still have enough information so tourists will not get lost. Let’s do something similar with diagrams of spacetime.

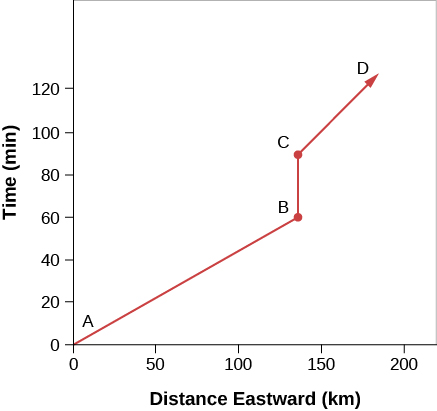

[link], for example, shows the progress of a motorist driving east on a stretch of road in Kansas where the countryside is absolutely flat. Since our motorist is traveling only in the east-west direction and the terrain is flat, we can ignore the other two dimensions of space. The amount of time elapsed since he left home is shown on the y-axis, and the distance traveled eastward is shown on the x-axis. From A to B he drove at a uniform speed; unfortunately, it was too fast a uniform speed and a police car spotted him. From B to C he stopped to receive his ticket and made no progress through space, only through time. From C to D he drove more slowly because the police car was behind him.

Now let’s try illustrating the distortions of spacetime in two dimensions. In this case, we will (in our imaginations) use a rubber sheet that can stretch or warp if we put objects on it.

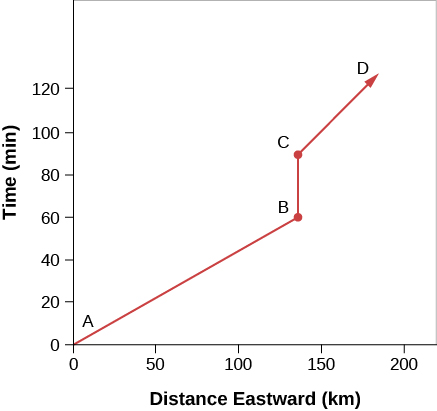

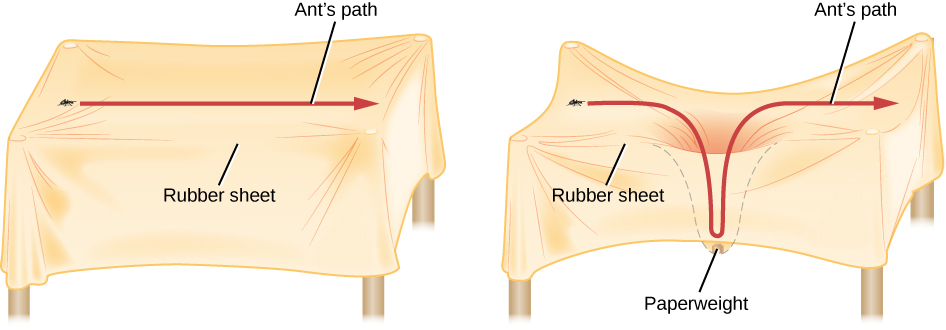

Let’s imagine stretching our rubber sheet taut on four posts. To complete the analogy, we need something that normally travels in a straight line (as light does). Suppose we have an extremely intelligent ant—a friend of the comic book superhero Ant-Man, perhaps—that has been trained to walk in a straight line.

We begin with just the rubber sheet and the ant, simulating empty space with no mass in it. We put the ant on one side of the sheet and it walks in a beautiful straight line over to the other side ([link]). We next put a small grain of sand on the rubber sheet. The sand does distort the sheet a tiny bit, but this is not a distortion that we or the ant can measure. If we send the ant so it goes close to, but not on top of, the sand grain, it has little trouble continuing to walk in a straight line.

Now we grab something with a little more mass—say, a small pebble. It bends or distorts the sheet just a bit around its position. If we send the ant into this region, it finds its path slightly altered by the distortion of the sheet. The distortion is not large, but if we follow the ant’s path carefully, we notice it deviating slightly from a straight line.

The effect gets more noticeable as we increase the mass of the object that we put on the sheet. Let’s say we now use a massive paperweight. Such a heavy object distorts or warps the rubber sheet very effectively, putting a good sag in it. From our point of view, we can see that the sheet near the paperweight is no longer straight.

Now let’s again send the ant on a journey that takes it close to, but not on top of, the paperweight. Far away from the paperweight, the ant has no trouble doing its walk, which looks straight to us. As it nears the paperweight, however, the ant is forced down into the sag. It must then climb up the other side before it can return to walking on an undistorted part of the sheet. All this while, the ant is following the shortest path it can, but through no fault of its own (after all, ants can’t fly, so it has to stay on the sheet) this path is curved by the distortion of the sheet itself.

In the same way, according to Einstein’s theory, light always follows the shortest path through spacetime. But the mass associated with large concentrations of matter distorts spacetime, and the shortest, most direct paths are no longer straight lines, but curves.

How large does a mass have to be before we can measure a change in the path followed by light? In 1916, when Einstein first proposed his theory, no distortion had been detected at the surface of Earth (so Earth might have played the role of the grain of sand in our analogy). Something with a mass like our Sun’s was necessary to detect the effect Einstein was describing (we will discuss how this effect was measured using the Sun in the next section).

The paperweight in our analogy might be a white dwarf or a neutron star. The distortion of spacetime is greater near the surfaces of these compact, massive objects than near the surface of the Sun. And when, to return to the situation described at the beginning of the chapter, a star core with more than three times the mass of the Sun collapses forever, the distortions of spacetime very close to it can become truly mind-boggling.

By considering the consequences of the equivalence principle, Einstein concluded that we live in a curved spacetime. The distribution of matter determines the curvature of spacetime; other objects (and even light) entering a region of spacetime must follow its curvature. Light must change its path near a massive object not because light is bent by gravity, but because spacetime is.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: