By the end of this section, you will be able to:

In the previous section, we indicated that that open clusters are younger than globular clusters, and associations are typically even younger. In this section, we will show how we determine the ages of these star clusters. The key observation is that the stars in these different types of clusters are found in different places in the H–R diagram, and we can use their locations in the diagram in combination with theoretical calculations to estimate how long they have lived.

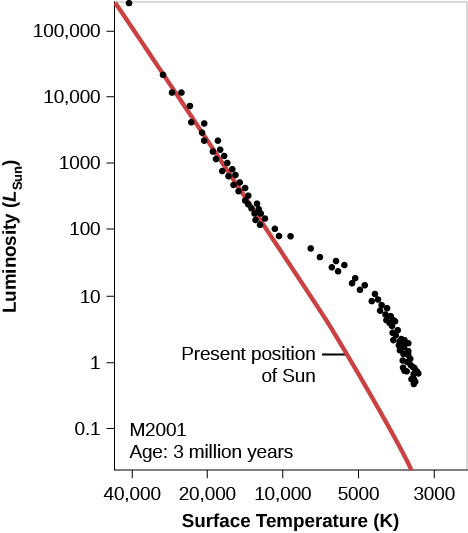

What does theory predict for the H–R diagram of a cluster whose stars have recently condensed from an interstellar cloud? Remember that at every stage of evolution, massive stars evolve more quickly than their lower-mass counterparts. After a few million years (“recently” for astronomers), the most massive stars should have completed their contraction phase and be on the main sequence, while the less massive ones should be off to the right, still on their way to the main sequence. These ideas are illustrated in [link], which shows the H–R diagram calculated by R. Kippenhahn and his associates at Munich University for a hypothetical cluster with an age of 3 million years.

There are real star clusters that fit this description. The first to be studied (in about 1950) was NGC 2264, which is still associated with the region of gas and dust from which it was born ([link]).

The NGC 2264 cluster’s H–R diagram is shown in [link]. The cluster in the middle of the Orion Nebula (shown in [link] and [link]) is in a similar stage of evolution.

![Compare this H–R diagram to that in [link]; although the points scatter a bit more here, the theoretical and observational diagrams are remarkably, and satisfyingly, similar. In this plot the vertical axis is labeled “Luminosity (LSun)” and goes from 0.1 at the bottom to 100,000 at the top. The horizontal axis is labeled “Surface Temperature (K)” and goes from 40,000 on the left to 3,000 on the right. The zero-age main sequence is drawn as a red diagonal line starting just above 100,000 LSun at the top of the graph down to about 4000 K at the bottom. Over plotted are the observed values of stars in N G C 2264, shown as black dots. Stars lie on the line until about 10000 K and 10 LSun, below which the stars reside above the main sequence.](../resources/OSC_Astro_22_03_NGC.jpg)

As clusters get older, their H–R diagrams begin to change. After a short time (less than a million years after they reach the main sequence), the most massive stars use up the hydrogen in their cores and evolve off the main sequence to become red giants and supergiants. As more time passes, stars of lower mass begin to leave the main sequence and make their way to the upper right of the H–R diagram.

To see the evolution of a star cluster in a dwarf galaxy, you can watch this brief animation of how its H–R diagram changes.

[link] is a photograph of NGC 3293, a cluster that is about 10 million years old. The dense clouds of gas and dust are gone. One massive star has evolved to become a red giant and stands out as an especially bright orange member of the cluster.

[link] shows the H–R diagram of the open cluster M41, which is roughly 100 million years old; by this time, a significant number of stars have moved off to the right and become red giants. Note the gap that appears in this H–R diagram between the stars near the main sequence and the red giants. A gap does not necessarily imply that stars avoid a region of certain temperatures and luminosities. In this case, it simply represents a domain of temperature and luminosity through which stars evolve very quickly. We see a gap for M41 because at this particular moment, we have not caught a star in the process of scurrying across this part of the diagram.

![(a) Cluster M41 is older than NGC 2264 (see [link]) and contains several red giants. Some of its more massive stars are no longer close to the zero-age main sequence (red line). (b) This ground-based photograph shows the open cluster M41. Note that it contains several orange-color stars. These are stars that have exhausted hydrogen in their centers, and have swelled up to become red giants. (credit b: modification of work by NOAO/AURA/NSF) In panel (a), on the left, the vertical axis is labeled “Luminosity (LSun)” and goes from 0.1 at the bottom to 100,000 at the top. The horizontal axis is labeled “Surface Temperature (K)” and goes from 40,000 on the left to 3000 on the right. The zero-age main sequence is drawn as a red diagonal line starting just above 100,000 LSun at the top of the graph down to about 4000 K at the bottom. Over plotted are the observed values of the stars in M 41. Approximately half of the stars lie above the main sequence until around 9000 K and 50 LSun, below which the stars all lie on the main sequence. On the right side of the diagram, a small grouping of giant stars are centered around 4000 K and 50 LSun. Panel (b), on the right, shows a photograph of the open cluster M 41.](../resources/OSC_Astro_22_03_Giant.jpg)

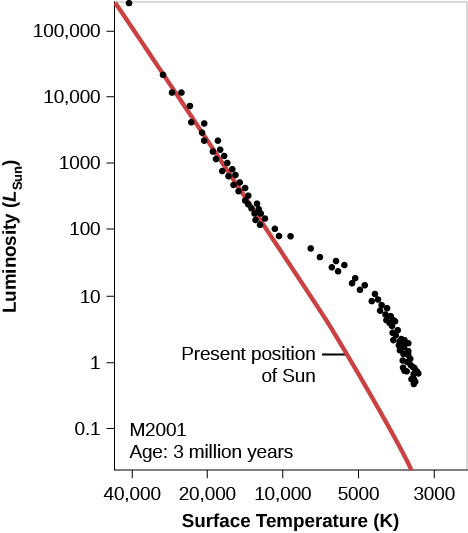

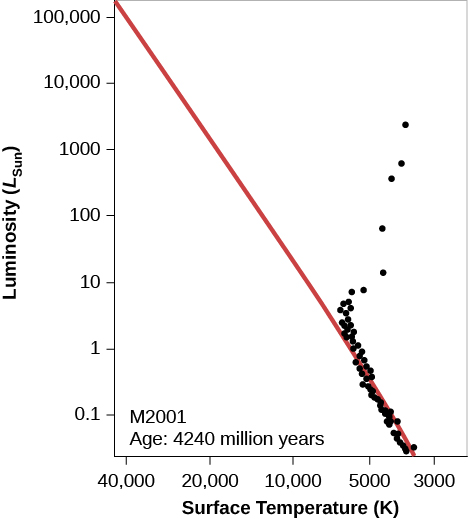

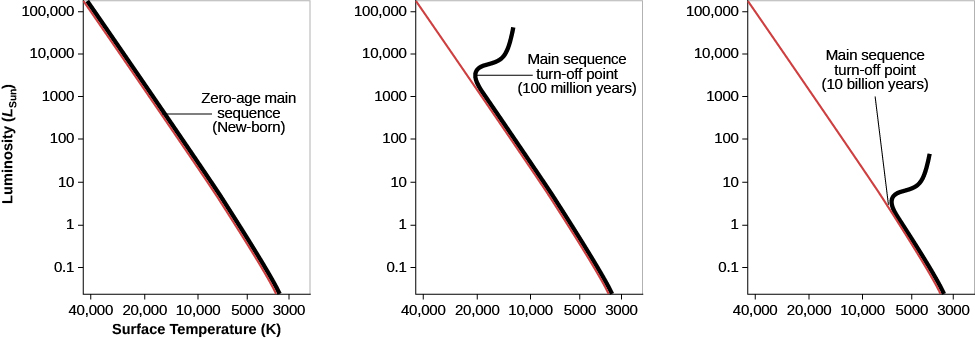

After 4 billion years have passed, many more stars, including stars that are only a few times more massive than the Sun, have left the main sequence ([link]). This means that no stars are left near the top of the main sequence; only the low-mass stars near the bottom remain. The older the cluster, the lower the point on the main sequence (and the lower the mass of the stars) where stars begin to move toward the red giant region. The location in the H–R diagram where the stars have begun to leave the main sequence is called the main-sequence turnoff.

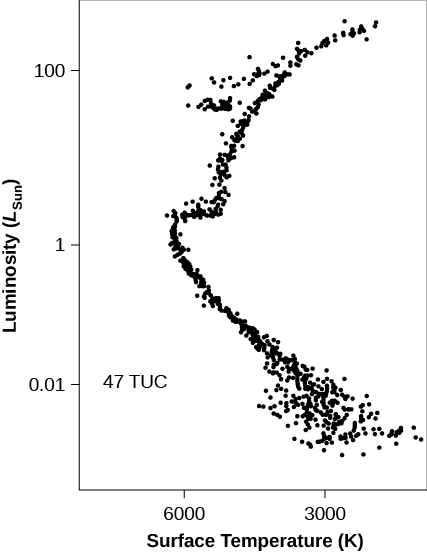

The oldest clusters of all are the globular clusters. [link] shows the H–R diagram of globular cluster 47 Tucanae. Notice that the luminosity and temperature scales are different from those of the other H–R diagrams in this chapter. In [link], for example, the luminosity scale on the left side of the diagram goes from 0.1 to 100,000 times the Sun’s luminosity. But in [link], the luminosity scale has been significantly reduced in extent. So many stars in this old cluster have had time to turn off the main sequence that only the very bottom of the main sequence remains.

Check out this brief NASA video with a 3-D visualization of how an H–R diagram is created for the globular cluster Omega Centauri.

Just how old are the different clusters we have been discussing? To get their actual ages (in years), we must compare the appearances of our calculated H–R diagrams of different ages to observed H–R diagrams of real clusters. In practice, astronomers use the position at the top of the main sequence (that is, the luminosity at which stars begin to move off the main sequence to become red giants) as a measure of the age of a cluster (the main-sequence turnoff we discussed previously). For example, we can compare the luminosities of the brightest stars that are still on the main sequence in [link] and [link].

Using this method, some associations and open clusters turn out to be as young as 1 million years old, while others are several hundred million years old. Once all of the interstellar matter surrounding a cluster has been used to form stars or has dispersed and moved away from the cluster, star formation ceases, and stars of progressively lower mass move off the main sequence, as shown in [link], [link], and [link].

To our surprise, even the youngest of the globular clusters in our Galaxy are found to be older than the oldest open cluster. All of the globular clusters have main sequences that turn off at a luminosity less than that of the Sun. Star formation in these crowded systems ceased billions of years ago, and no new stars are coming on to the main sequence to replace the ones that have turned off (see [link]).

Indeed, the globular clusters are the oldest structures in our Galaxy (and in other galaxies as well). The youngest have ages of about 11 billion years and some appear to be even older. Since these are the oldest objects we know of, this estimate is one of the best limits we have on the age of the universe itself—it must be at least 11 billion years old. We will return to the fascinating question of determining the age of the entire universe in the chapter on The Big Bang.

The H–R diagram of stars in a cluster changes systematically as the cluster grows older. The most massive stars evolve most rapidly. In the youngest clusters and associations, highly luminous blue stars are on the main sequence; the stars with the lowest masses lie to the right of the main sequence and are still contracting toward it. With passing time, stars of progressively lower masses evolve away from (or turn off) the main sequence. In globular clusters, which are all at least 11 billion years old, there are no luminous blue stars at all. Astronomers can use the turnoff point from the main sequence to determine the age of a cluster.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: