By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Fusion of protons can occur in the center of the Sun only if the temperature exceeds 12 million K. How do we know that the Sun is actually this hot? To determine what the interior of the Sun might be like, it is necessary to resort to complex calculations. Since we can’t see the interior of the Sun, we have to use our understanding of physics, combined with what we see at the surface, to construct a mathematical model of what must be happening in the interior. Astronomers use observations to build a computer program containing everything they think they know about the physical processes going on in the Sun’s interior. The computer then calculates the temperature and pressure at every point inside the Sun and determines what nuclear reactions, if any, are taking place. For some calculations, we can use observations to determine whether the computer program is producing results that match what we see. In this way, the program evolves with ever-improving observations.

The computer program can also calculate how the Sun will change with time. After all, the Sun must change. In its center, the Sun is slowly depleting its supply of hydrogen and creating helium instead. Will the Sun get hotter? Cooler? Larger? Smaller? Brighter? Fainter? Ultimately, the changes in the center could be catastrophic, since eventually all the hydrogen fuel hot enough for fusion will be exhausted. Either a new source of energy must be found, or the Sun will cease to shine. We will describe the ultimate fate of the Sun in later chapters. For now, let’s look at some of the things we must teach the computer about the Sun in order to carry out such calculations.

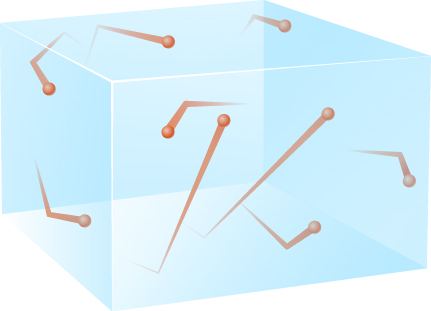

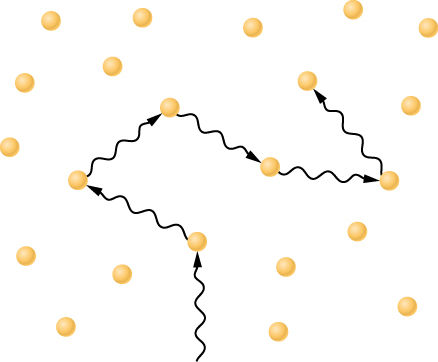

The Sun is so hot that all of the material in it is in the form of an ionized gas, called a plasma. Plasma acts much like a hot gas, which is easier to describe mathematically than either liquids or solids. The particles that constitute a gas are in rapid motion, frequently colliding with one another. This constant bombardment is the pressure of the gas ([link]).

More particles within a given volume of gas produce more pressure because the combined impact of the moving particles increases with their number. The pressure is also greater when the molecules or atoms are moving faster. Since the molecules move faster when the temperature is hotter, higher temperatures produce higher pressure.

The Sun, like the majority of other stars, is stable; it is neither expanding nor contracting. Such a star is said to be in a condition of equilibrium. All the forces within it are balanced, so that at each point within the star, the temperature, pressure, density, and so on are maintained at constant values. We will see in later chapters that even these stable stars, including the Sun, are changing as they evolve, but such evolutionary changes are so gradual that, for all intents and purposes, the stars are still in a state of equilibrium at any given time.

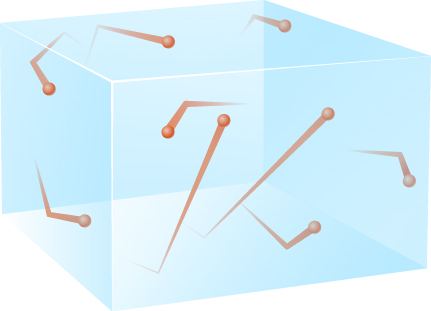

The mutual gravitational attraction between the masses of various regions within the Sun produces tremendous forces that tend to collapse the Sun toward its center. Yet we know from the history of Earth that the Sun has been emitting roughly the same amount of energy for billions of years, so clearly it has managed to resist collapse for a very long time. The gravitational forces must therefore be counterbalanced by some other force. That force is due to the pressure of gases within the Sun ([link]). Calculations show that, in order to exert enough pressure to prevent the Sun from collapsing due to the force of gravity, the gases at its center must be maintained at a temperature of 15 million K. Think about what this tells us. Just from the fact that the Sun is not contracting, we can conclude that its temperature must indeed be high enough at the center for protons to undergo fusion.

The Sun maintains its stability in the following way. If the internal pressure in such a star were not great enough to balance the weight of its outer parts, the star would collapse somewhat, contracting and building up the pressure inside. On the other hand, if the pressure were greater than the weight of the overlying layers, the star would expand, thus decreasing the internal pressure. Expansion would stop, and equilibrium would again be reached when the pressure at every internal point equaled the weight of the stellar layers above that point. An analogy is an inflated balloon, which will expand or contract until an equilibrium is reached between the pressure of the air inside and outside. The technical term for this condition is hydrostatic equilibrium. Stable stars are all in hydrostatic equilibrium; so are the oceans of Earth as well as Earth’s atmosphere. The air’s own pressure keeps it from falling to the ground.

As everyone who has ever left a window open on a cold winter night knows, heat always flows from hotter to cooler regions. As energy filters outward toward the surface of a star, it must be flowing from inner, hotter regions. The temperature cannot ordinarily get cooler as we go inward in a star, or energy would flow in and heat up those regions until they were at least as hot as the outer ones. Scientists conclude that the temperature is highest at the center of a star, dropping to lower and lower values toward the stellar surface. (The high temperature of the Sun’s chromosphere and corona may therefore appear to be a paradox. But remember from The Sun: A Garden-Variety Star that these high temperatures are maintained by magnetic effects, which occur in the Sun’s atmosphere.)

The outward flow of energy through a star robs it of its internal heat, and the star would cool down if that energy were not replaced. Similarly, a hot iron begins to cool as soon as it is unplugged from its source of electric energy. Therefore, a source of fresh energy must exist within each star. In the Sun’s case, we have seen that this energy source is the ongoing fusion of hydrogen to form helium.

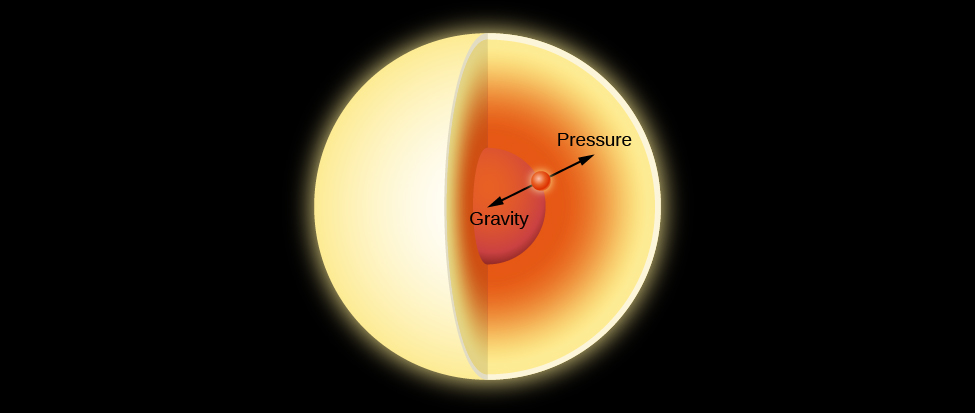

Since the nuclear reactions that generate the Sun’s energy occur deep within it, the energy must be transported from the center of the Sun to its surface—where we see it in the form of both heat and light. There are three ways in which energy can be transferred from one place to another. In conduction, atoms or molecules pass on their energy by colliding with others nearby. This happens, for example, when the handle of a metal spoon heats up as you stir a cup of hot coffee. In convection, currents of warm material rise, carrying their energy with them to cooler layers. A good example is hot air rising from a fireplace. In radiation, energetic photons move away from hot material and are absorbed by some material to which they convey some or all of their energy. You can feel this when you put your hand close to the coils of an electric heater, allowing infrared photons to heat up your hand. Conduction and convection are both important in the interiors of planets. In stars, which are much more transparent, radiation and convection are important, whereas conduction can usually be ignored.

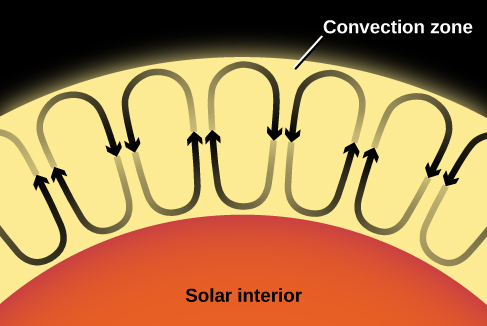

Stellar convection occurs as currents of hot gas flow up and down through the star ([link]). Such currents travel at moderate speeds and do not upset the overall stability of the star. They don’t even result in a net transfer of mass either inward or outward because, as hot material rises, cool material falls and replaces it. This results in a convective circulation of rising and falling cells as seen in [link]. In much the same way, heat from a fireplace can stir up air currents in a room, some rising and some falling, without driving any air into or out the room. Convection currents carry heat very efficiently outward through a star. In the Sun, convection turns out to be important in the central regions and near the surface.

Unless convection occurs, the only significant mode of energy transport through a star is by electromagnetic radiation. Radiation is not an efficient means of energy transport in stars because gases in stellar interiors are very opaque, that is, a photon does not go far (in the Sun, typically about 0.01 meter) before it is absorbed. (The processes by which atoms and ions can interrupt the outward flow of photons—such as becoming ionized—were discussed in the section on the Formation of Spectral Lines.) The absorbed energy is always reemitted, but it can be reemitted in any direction. A photon absorbed when traveling outward in a star has almost as good a chance of being radiated back toward the center of the star as toward its surface.

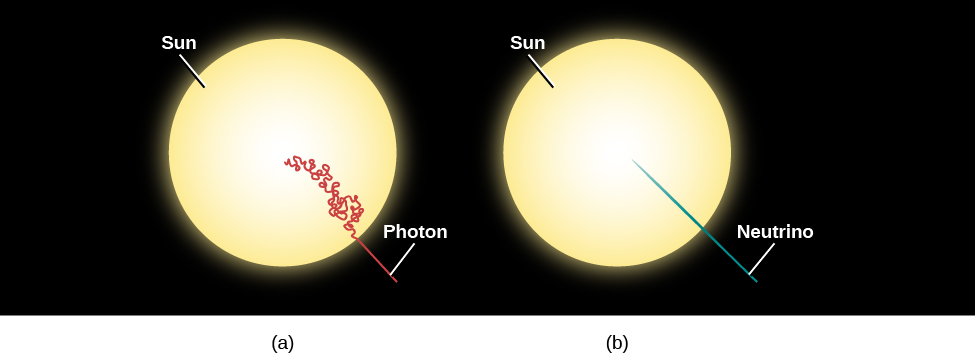

A particular quantity of energy, therefore, zigzags around in an almost random manner and takes a long time to work its way from the center of a star to its surface ([link]). Estimates are somewhat uncertain, but in the Sun, as we saw, the time required is probably between 100,000 and 1,000,000 years. If the photons were not absorbed and reemitted along the way, they would travel at the speed of light and could reach the surface in a little over 2 seconds, just as neutrinos do ([link]).

The three ways that heat energy moves from higher-temperature regions to cooler regions are all used in cooking, and this is important to all of us who enjoy making or eating food.

Conduction is heat transfer by physical contact during which the energetic motion of particles in one region spread to other regions and even to adjacent objects in close contact. A tasty example of this is cooking a steak on a hot iron skillet. When a flame makes the bottom of a skillet hot, the particles in it vibrate actively and collide with neighboring particles, spreading the heat energy throughout the skillet (the ability to spread heat uniformly is a key criterion for selecting materials for cookware). A steak sitting on the surface of the skillet picks up heat energy by the particles in the surface of the skillet colliding with particles on the surface of the steak. Many cooks will put a little oil on the pan, and this layer of oil, besides preventing sticking, increases heat transfer by filling in gaps and increasing the contact surface area.

Convection is heat transfer by the motion of matter that rises because it is hot and less dense. Heating a fluid makes it expand, which makes it less dense, so it rises. An oven is a great example of this: the fire is at the bottom of the oven and heats the air down there, causing it to expand (becoming less dense), so it rises up to where the food is. The rising hot air carries the heat from the fire to the food by convection. This is how conventional ovens work. You may also be familiar with convection ovens that use a fan to circulate hot air for more even cooking. A scientist would object to that name because normal non-fan ovens that rely on hot air rising to circulate the heat are convection ovens; technically, the ovens that use fans to help move heat are “advection” ovens. (You may not have heard about this because the scientists who complain loudly about misusing the terms convection and advection don’t get out much.)

Radiation is the transfer of heat energy by electromagnetic radiation. Although microwave ovens are an obvious example of using radiation to heat food, a simpler example is a toy oven. Toy ovens are powered by a very bright light bulb. The child-chefs prepare a mix for brownies or cookies, put it into a tray, and place it in the toy oven under the bright light bulb. The light and heat from the bulb hit the brownie mix and cook it. If you have ever put your hand near a bright light, you have undoubtedly noticed your hand getting warmed by the light.

Scientists use the principles we have just described to calculate what the Sun’s interior is like. These physical ideas are expressed as mathematical equations that are solved to determine the values of temperature, pressure, density, the efficiency with which photons are absorbed, and other physical quantities throughout the Sun. The solutions obtained, based on a specific set of physical assumptions, provide a theoretical model for the interior of the Sun.

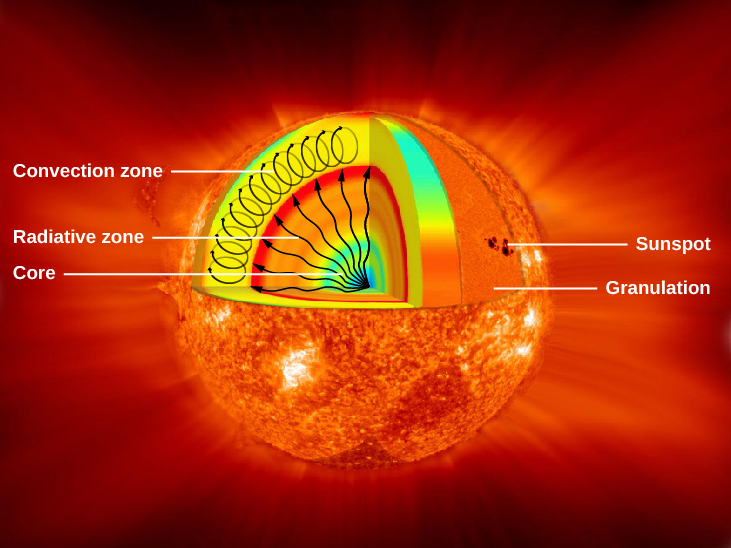

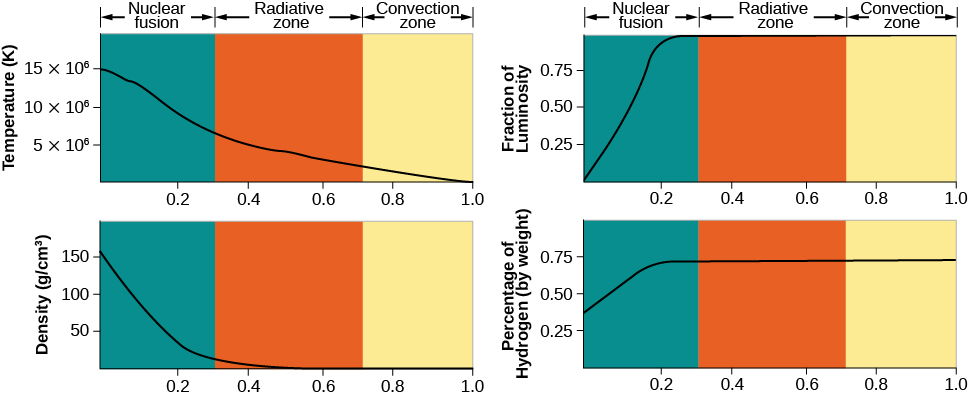

[link] schematically illustrates the predictions of a theoretical model for the Sun’s interior. Energy is generated through fusion in the core of the Sun, which extends only about one-quarter of the way to the surface but contains about one-third of the total mass of the Sun. At the center, the temperature reaches a maximum of approximately 15 million K, and the density is nearly 150 times that of water. The energy generated in the core is transported toward the surface by radiation until it reaches a point about 70% of the distance from the center to the surface. At this point, convection begins, and energy is transported the rest of the way, primarily by rising columns of hot gas.

[link] shows how the temperature, density, rate of energy generation, and composition vary from the center of the Sun to its surface.

Even though we cannot see inside the Sun, it is possible to calculate what its interior must be like. As input for these calculations, we use what we know about the Sun. It is made entirely of hot gas. Apart from some very tiny changes, the Sun is neither expanding nor contracting (it is in hydrostatic equilibrium) and puts out energy at a constant rate. Fusion of hydrogen occurs in the center of the Sun, and the energy generated is carried to the surface by radiation and then convection. A solar model describes the structure of the Sun’s interior. Specifically, it describes how pressure, temperature, mass, and luminosity depend on the distance from the center of the Sun.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: