By the end of this section, you will be able to:

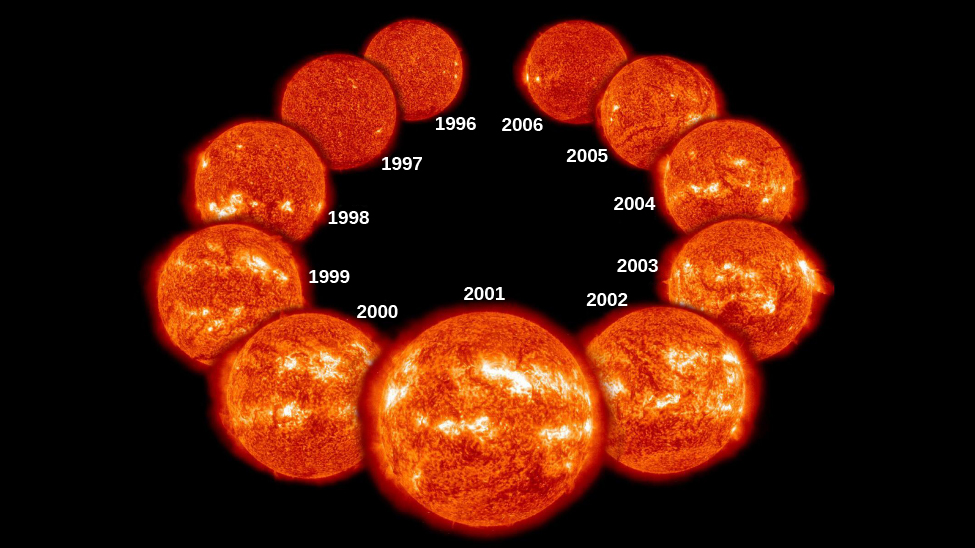

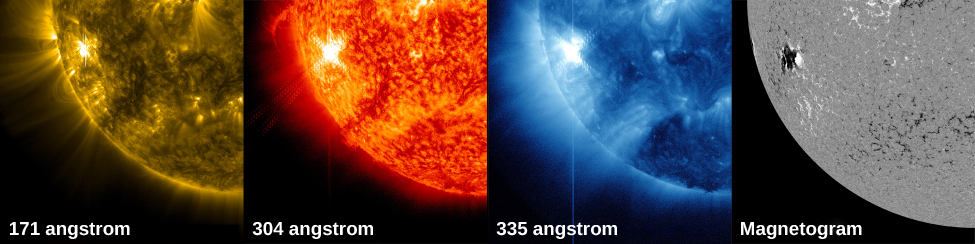

Sunspots are not the only features that vary during a solar cycle. There are dramatic changes in the chromosphere and corona as well. To see what happens in the chromosphere, we must observe the emission lines from elements such as hydrogen and calcium, which emit useful spectral lines at the temperatures in that layer. The hot corona, on the other hand, can be studied by observations of X-rays and of extreme ultraviolet and other wavelengths at high energies.

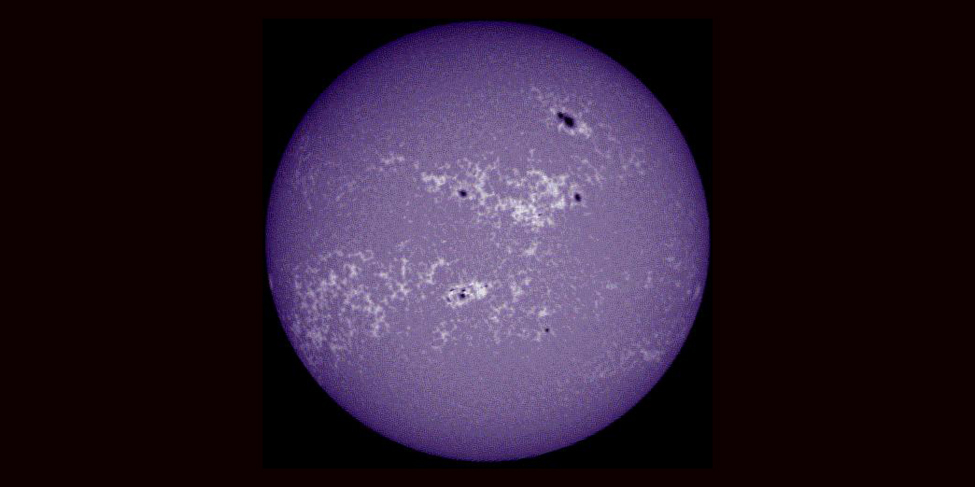

As we saw, emission lines of hydrogen and calcium are produced in the hot gases of the chromosphere. Astronomers routinely photograph the Sun through filters that transmit light only at the wavelengths that correspond to these emission lines. Pictures taken through these special filters show bright “clouds” in the chromosphere around sunspots; these bright regions are known as plages ([link]). These are regions within the chromosphere that have higher temperature and density than their surroundings. The plages actually contain all of the elements in the Sun, not just hydrogen and calcium. It just happens that the spectral lines of hydrogen and calcium produced by these clouds are bright and easy to observe.

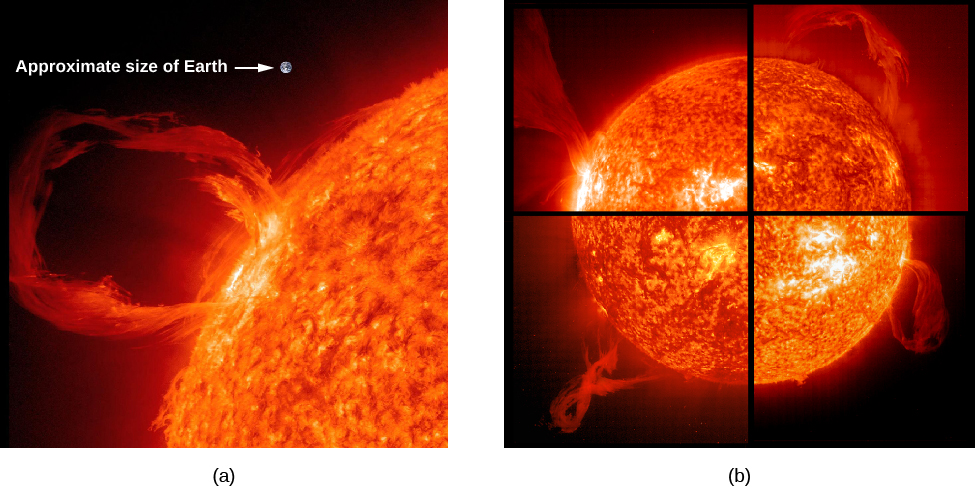

Moving higher into the Sun’s atmosphere, we come to the spectacular phenomena called prominences ([link]), which usually originate near sunspots. Eclipse observers often see prominences as red features rising above the eclipsed Sun and reaching high into the corona. Some, the quiescent prominences, are graceful loops of plasma (ionized gas) that can remain nearly stable for many hours or even days. The relatively rare eruptive prominences appear to send matter upward into the corona at high speeds, and the most active surge prominences may move as fast as 1300 kilometers per second (almost 3 million miles per hour). Some eruptive prominences have reached heights of more than 1 million kilometers above the photosphere; Earth would be completely lost inside one of those awesome displays ([link]).

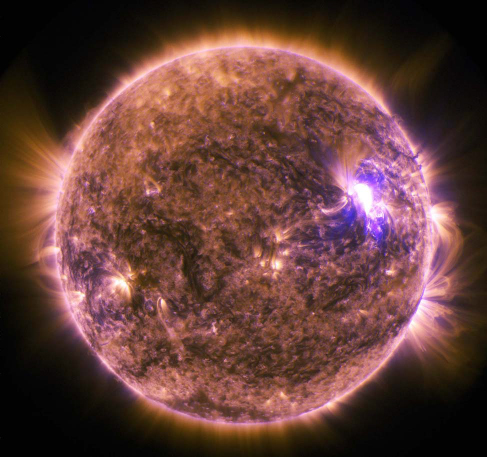

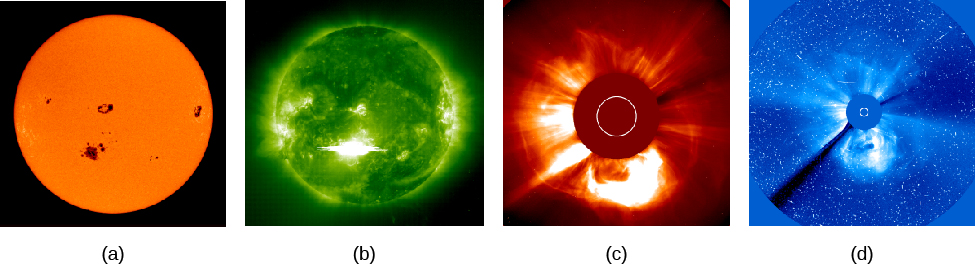

The most violent event on the surface of the Sun is a rapid eruption called a solar flare ([link]). A typical flare lasts for 5 to 10 minutes and releases a total amount of energy equivalent to that of perhaps a million hydrogen bombs. The largest flares last for several hours and emit enough energy to power the entire United States at its current rate of electrical consumption for 100,000 years. Near sunspot maximum, small flares occur several times per day, and major ones may occur every few weeks.

Flares, like the one shown in [link], are often observed in the red light of hydrogen, but the visible emission is only a tiny fraction of the energy released when a solar flare explodes. At the moment of the explosion, the matter associated with the flare is heated to temperatures as high as 10 million K. At such high temperatures, a flood of X-ray and ultraviolet radiation is emitted.

Flares seem to occur when magnetic fields pointing in opposite directions release energy by interacting with and destroying each other—much as a stretched rubber band releases energy when it breaks.

What is different about flares is that their magnetic interactions cover a large volume in the solar corona and release a tremendous amount of electromagnetic radiation. In some cases, immense quantities of coronal material—mainly protons and electrons—may also be ejected at high speeds (500–1000 kilometers per second) into interplanetary space. Such a coronal mass ejection (CME) can affect Earth in a number of ways (which we will discuss in the section on space weather).

See a coronal mass ejection recorded by the Solar Dynamics Observatory.

To bring the discussion of the last two sections together, astronomers now realize that sunspots, flares, and bright regions in the chromosphere and corona tend to occur together on the Sun in time and space. That is, they all tend to have similar longitudes and latitudes, but they are located at different heights in the atmosphere. Because they all occur together, they vary with the sunspot cycle.

For example, flares are more likely to occur near sunspot maximum, and the corona is much more conspicuous at that time (see [link]). A place on the Sun where a number of these phenomena are seen is called an active region ([link]). As you might deduce from our earlier discussion, active regions are always associated with strong magnetic fields.

Signs of more intense solar activity, an increase in the number of sunspots, as well as prominences, plages, solar flares, and coronal mass ejections, all tend to occur in active regions—that is, in places on the Sun with the same latitude and longitude but at different heights in the atmosphere. Active regions vary with the solar cycle, just like sunspots do.

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: