By the end of this section, you will be able to:

Until now, we have considered the Sun and a planet (or a planet and one of its moons) as nothing more than a pair of bodies revolving around each other. In fact, all the planets exert gravitational forces upon one another as well. These interplanetary attractions cause slight variations from the orbits than would be expected if the gravitational forces between planets were neglected. The motion of a body that is under the gravitational influence of two or more other bodies is very complicated and can be calculated properly only with large computers. Fortunately, astronomers have such computers at their disposal in universities and government research institutes.

As an example, suppose you have a cluster of a thousand stars all orbiting a common center (such clusters are quite common, as we shall see in Star Clusters). If we know the exact position of each star at any given instant, we can calculate the combined gravitational force of the entire group on any one member of the cluster. Knowing the force on the star in question, we can therefore find how it will accelerate. If we know how it was moving to begin with, we can then calculate how it will move in the next instant of time, thus tracking its motion.

However, the problem is complicated by the fact that the other stars are also moving and thus changing the effect they will have on our star. Therefore, we must simultaneously calculate the acceleration of each star produced by the combination of the gravitational attractions of all the others in order to track the motions of all of them, and hence of any one. Such complex calculations have been carried out with modern computers to track the evolution of hypothetical clusters of stars with up to a million members ([link]).

Within the solar system, the problem of computing the orbits of planets and spacecraft is somewhat simpler. We have seen that Kepler’s laws, which do not take into account the gravitational effects of the other planets on an orbit, really work quite well. This is because these additional influences are very small in comparison with the dominant gravitational attraction of the Sun. Under such circumstances, it is possible to treat the effects of other bodies as small perturbations (or disturbances). During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, mathematicians developed many elegant techniques for calculating perturbations, permitting them to predict very precisely the positions of the planets. Such calculations eventually led to the prediction and discovery of a new planet in 1846.

The discovery of the eighth planet, Neptune, was one of the high points in the development of gravitational theory. In 1781, William Herschel, a musician and amateur astronomer, accidentally discovered the seventh planet, Uranus. It happens that Uranus had been observed a century before, but in none of those earlier sightings was it recognized as a planet; rather, it was simply recorded as a star. Herschel’s discovery showed that there could be planets in the solar system too dim to be visible to the unaided eye, but ready to be discovered with a telescope if we just knew where to look.

By 1790, an orbit had been calculated for Uranus using observations of its motion in the decade following its discovery. Even after allowance was made for the perturbing effects of Jupiter and Saturn, however, it was found that Uranus did not move on an orbit that exactly fit the earlier observations of it made since 1690. By 1840, the discrepancy between the positions observed for Uranus and those predicted from its computed orbit amounted to about 0.03°—an angle barely discernable to the unaided eye but still larger than the probable errors in the orbital calculations. In other words, Uranus just did not seem to move on the orbit predicted from Newtonian theory.

In 1843, John Couch Adams, a young Englishman who had just completed his studies at Cambridge, began a detailed mathematical analysis of the irregularities in the motion of Uranus to see whether they might be produced by the pull of an unknown planet. He hypothesized a planet more distant from the Sun than Uranus, and then determined the mass and orbit it had to have to account for the departures in Uranus’ orbit. In October 1845, Adams delivered his results to George Airy, the British Astronomer Royal, informing him where in the sky to find the new planet. We now know that Adams’ predicted position for the new body was correct to within 2°, but for a variety of reasons, Airy did not follow up right away.

Meanwhile, French mathematician Urbain Jean Joseph Le Verrier, unaware of Adams or his work, attacked the same problem and published its solution in June 1846. Airy, noting that Le Verrier’s predicted position for the unknown planet agreed to within 1° with that of Adams, suggested to James Challis, Director of the Cambridge Observatory, that he begin a search for the new object. The Cambridge astronomer, having no up-to-date star charts of the Aquarius region of the sky where the planet was predicted to be, proceeded by recording the positions of all the faint stars he could observe with his telescope in that location. It was Challis’ plan to repeat such plots at intervals of several days, in the hope that the planet would distinguish itself from a star by its motion. Unfortunately, he was negligent in examining his observations; although he had actually seen the planet, he did not recognize it.

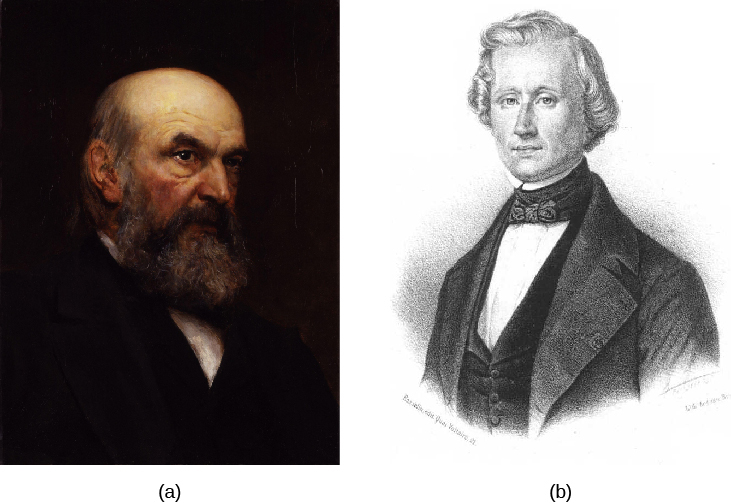

About a month later, Le Verrier suggested to Johann Galle, an astronomer at the Berlin Observatory, that he look for the planet. Galle received Le Verrier’s letter on September 23, 1846, and, possessing new charts of the Aquarius region, found and identified the planet that very night. It was less than a degree from the position Le Verrier predicted. The discovery of the eighth planet, now known as Neptune (the Latin name for the god of the sea), was a major triumph for gravitational theory for it dramatically confirmed the generality of Newton’s laws. The honor for the discovery is properly shared by the two mathematicians, Adams and Le Verrier ([link]).

We should note that the discovery of Neptune was not a complete surprise to astronomers, who had long suspected the existence of the planet based on the “disobedient” motion of Uranus. On September 10, 1846, two weeks before Neptune was actually found, John Herschel, son of the discoverer of Uranus, remarked in a speech before the British Association, “We see [the new planet] as Columbus saw America from the shores of Spain. Its movements have been felt trembling along the far-reaching line of our analysis with a certainty hardly inferior to ocular demonstration.”

This discovery was a major step forward in combining Newtonian theory with painstaking observations. Such work continues in our own times with the discovery of planets around other stars.

For the fuller story of how Neptune was predicted and found (and the effect of the discovery on the search for Pluto), you can read this page on the mathematical discovery of planets.

When Copernicus, Kepler, Galileo, and Newton formulated the fundamental rules that underlie everything in the physical world, they changed much more than the face of science. For some, they gave humanity the courage to let go of old superstitions and see the world as rational and manageable; for others, they upset comforting, ordered ways that had served humanity for centuries, leaving only a dry, “mechanical clockwork” universe in their wake.

Poets of the time reacted to such changes in their work and debated whether the new world picture was an appealing or frightening one. John Donne (1573–1631), in a poem called “Anatomy of the World,” laments the passing of the old certainties:

The new Philosophy [science] calls all in doubt,* * *

The element of fire is quite put out;* * *

The Sun is lost, and th’ earth, and no man’s wit* * *

Can well direct him where to look for it.</q>

(Here the “element of fire” refers also to the sphere of fire, which medieval thought placed between Earth and the Moon.)

By the next century, however, poets like Alexander Pope were celebrating Newton and the Newtonian world view. Pope’s famous couplet, written upon Newton’s death, goes

Nature, and nature’s laws lay hid in night.* * *

God said, Let Newton be! And all was light.</q>

In his 1733 poem, An Essay on Man, Pope delights in the complexity of the new views of the world, incomplete though they are:

Of man, what see we, but his station here,* * *

From which to reason, to which refer? . . .* * *

He, who thro’ vast immensity can pierce,* * *

See worlds on worlds compose one universe,* * *

Observe how system into system runs,* * *

What other planets circle other suns,* * *

What vary’d being peoples every star,* * *

May tell why Heav’n has made us as we are . . .* * *

All nature is but art, unknown to thee;* * *

All chance, direction, which thou canst not see;* * *

All discord, harmony not understood;* * *

All partial evil, universal good:* * *

And, in spite of pride, in erring reason’s spite,* * *

One truth is clear, whatever is, is right. </q>

Poets and philosophers continued to debate whether humanity was exalted or debased by the new views of science. The nineteenth-century poet Arthur Hugh Clough (1819–1861) cries out in his poem “The New Sinai”:

And as old from Sinai’s top God said that God is one,* * *

By science strict so speaks He now to tell us, there is None!* * *

Earth goes by chemic forces; Heaven’s a Mécanique Celeste!* * *

And heart and mind of humankind a watchwork as the rest!</q>

(A “mécanique celeste” is a clockwork model to demonstrate celestial motions.)

The twentieth-century poet Robinson Jeffers (whose brother was an astronomer) saw it differently in a poem called “Star Swirls”:

There is nothing like astronomy to pull the stuff out of man.* * *

His stupid dreams and red-rooster importance:* * *

Let him count the star-swirls.</q>

Calculating the gravitational interaction of more than two objects is complicated and requires large computers. If one object (like the Sun in our solar system) dominates gravitationally, it is possible to calculate the effects of a second object in terms of small perturbations. This approach was used by John Couch Adams and Urbain Le Verrier to predict the position of Neptune from its perturbations of the orbit of Uranus and thus discover a new planet mathematically.

Christianson, G. “The Celestial Palace of Tycho Brahe.” Scientific American (February 1961): 118.

Gingerich, O. “Johannes Kepler and the Rudolphine Tables.” Sky & Telescope (December 1971): 328. Brief article on Kepler’s work.

Wilson, C. “How Did Kepler Discover His First Two Laws?” Scientific American (March 1972): 92.

Christianson, G. “Newton’s Principia: A Retrospective.” Sky & Telescope (July 1987): 18.

Cohen, I. “Newton’s Discovery of Gravity.” Scientific American (March 1981): 166.

Gingerich, O. “Newton, Halley, and the Comet.” Sky & Telescope (March 1986): 230.

Sullivant, R. “When the Apple Falls.” Astronomy (April 1998): 55. Brief overview.

Sheehan, W., et al. “The Case of the Pilfered Planet: Did the British Steal Neptune?” Scientific American (December 2004): 92.

Johannes Kepler: His Life, His Laws, and Time: http://kepler.nasa.gov/Mission/JohannesKepler/. From NASA’s Kepler mission.

Johannes Kepler: http://www.britannica.com/biography/Johannes-Kepler. Encyclopedia Britannica article.

Johannes Kepler: http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Kepler.html. MacTutor article with additional links.

Noble Dane: Images of Tycho Brahe: http://www.mhs.ox.ac.uk/tycho/index.htm. A virtual museum exhibit from Oxford.

Sir Isaac Newton: http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history//Biographies/Newton.html. MacTutor article with additional links.

Sir Isaac Newton: http://www.luminarium.org/sevenlit/newton/newtonbio.htm. Newton Biography at the Luminarium.

Adams, Airy, and the Discovery of Neptune: http://www.mikeoates.org/lassell/adams-airy.htm. A defense of Airy’s role by historian Alan Chapman.

Mathematical Discovery of Planets: http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Neptune\_and\_Pluto.html. MacTutor article.

“Harmony of the Worlds.” This third episode of Carl Sagan’s TV series Cosmos focuses on Kepler and his life and work.

Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler, and Planetary Motion: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x3ALuycrCwI. German-produced video, in English (14:27).

Beyond the Big Bang: Sir Isaac Newton’s Law of Gravity: http://www.history.com/topics/enlightenment/videos/beyond-the-big-bang-sir-isaac-newtons-law-of-gravity. From the History Channel (4:35).

Sir Isaac Newton versus Bill Nye: Epic Rap Battles of History: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8yis7GzlXNM. (2:47).

Richard Feynman: On the Discovery of Neptune: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FgXQffVgZRs. A brief black-and-white Caltech lecture (4:33).

State Kepler’s three laws in your own words.

Why did Kepler need Tycho Brahe’s data to formulate his laws?

Which has more mass: an armful of feathers or an armful of lead? Which has more volume: a kilogram of feathers or a kilogram of lead? Which has higher density: a kilogram of feathers or a kilogram of lead?

Explain how Kepler was able to find a relationship (his third law) between the orbital periods and distances of the planets that did not depend on the masses of the planets or the Sun.

Write out Newton’s three laws of motion in terms of what happens with the momentum of objects.

Which major planet has the largest . . .

Why do we say that Neptune was the first planet to be discovered through the use of mathematics?

Why was Brahe reluctant to provide Kepler with all his data at one time?

According to Kepler’s second law, where in a planet’s orbit would it be moving fastest? Where would it be moving slowest?

The gas pedal, the brakes, and the steering wheel all have the ability to accelerate a car—how?

Explain how a rocket can propel itself using Newton’s third law.

A certain material has a mass of 565 g while occupying 50 cm3 of space. What is this material? (Hint: Use [link].)

To calculate the momentum of an object, which properties of an object do you need to know?

To calculate the angular momentum of an object, which properties of an object do you need to know?

What was the great insight Newton had regarding Earth’s gravity that allowed him to develop the universal law of gravitation?

Which of these properties of an object best quantifies its inertia: velocity, acceleration, volume, mass, or temperature?

Pluto’s orbit is more eccentric than any of the major planets. What does that mean?

Why is Tycho Brahe often called “the greatest naked-eye astronomer” of all time?

Is it possible to escape the force of gravity by going into orbit around Earth? How does the force of gravity in the International Space Station (orbiting an average of 400 km above Earth’s surface) compare with that on the ground?

What is the momentum of an object whose velocity is zero? How does Newton’s first law of motion include the case of an object at rest?

Evil space aliens drop you and your fellow astronomy student 1 km apart out in space, very far from any star or planet. Discuss the effects of gravity on each of you.

A body moves in a perfectly circular path at constant speed. Are there forces acting in such a system? How do you know?

As friction with our atmosphere causes a satellite to spiral inward, closer to Earth, its orbital speed increases. Why?

Use a history book, an encyclopedia, or the internet to find out what else was happening in England during Newton’s lifetime and discuss what trends of the time might have contributed to his accomplishments and the rapid acceptance of his work.

Two asteroids begin to gravitationally attract one another. If one asteroid has twice the mass of the other, which one experiences the greater force? Which one experiences the greater acceleration?

How does the mass of an astronaut change when she travels from Earth to the Moon? How does her weight change?

If there is gravity where the International Space Station (ISS) is located above Earth, why doesn’t the space station get pulled back down to Earth?

Compare the density, weight, mass, and volume of a pound of gold to a pound of iron on the surface of Earth.

If identical spacecraft were orbiting Mars and Earth at identical radii (distances), which spacecraft would be moving faster? Why?

By what factor would a person’s weight be increased if Earth had 10 times its present mass, but the same volume?

Suppose astronomers find an earthlike planet that is twice the size of Earth (that is, its radius is twice that of Earth’s). What must be the mass of this planet such that the gravitational force (Fgravity) at the surface would be identical to Earth’s?

What is the semimajor axis of a circle of diameter 24 cm? What is its eccentricity?

If 24 g of material fills a cube 2 cm on a side, what is the density of the material?

If 128 g of material is in the shape of a brick 2 cm wide, 4 cm high, and 8 cm long, what is the density of the material?

If the major axis of an ellipse is 16 cm, what is the semimajor axis? If the eccentricity is 0.8, would this ellipse be best described as mostly circular or very elongated?

What is the average distance from the Sun (in astronomical units) of an asteroid with an orbital period of 8 years?

What is the average distance from the Sun (in astronomical units) of a planet with an orbital period of 45.66 years?

In 1996, astronomers discovered an icy object beyond Pluto that was given the designation 1996 TL 66. It has a semimajor axis of 84 AU. What is its orbital period according to Kepler’s third law?

You can also download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/2e737be8-ea65-48c3-aa0a-9f35b4c6a966@14.4

Attribution: